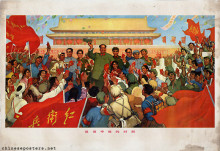

Detail from poster ‘Long live the victory of the proletarian revolutionary line...’, 1967

Kang Sheng (康生, 1898-1975) is undoubtedly one of the most hated of the early leaders of the CCP. As one of the driving forces behind the Rectification Movement (1942) and the Anti-Rightist Movement (1957), he made many enemies. Kang is considered as the creator of the Chinese Gulag, the Godfather of the Cultural Revolution, and was seen as an adviser of the Gang of Four.

He was born as Zhang Zongke in a landlord family in Jiaonan, Shandong Province. He joined the Party in 1925 and became active in the Shanghai branch, mainly in the organization and control departments. He took part in the Shanghai workers uprising in 1927, and managed to escape the subsequent massacre of communists ordered by Chiang Kai-shek. By 1928, he was operating already on the level of the Central Committee. He was sent to Moscow in 1933 to study Soviet security and intelligence techniques. In 1935, he adopted the nom de guerre of Kang Sheng. He left Moscow for Yan’an in 1937, where he first was active in the Central Party School, and later in the so-called Social Affairs Department, the chief security organ under the Central Committee, which he headed until 1946.

Kang was married to Cao Yi’ou, and maintained a simultaneous affair with her sister, Su Mei. At the same time, Kang was a close friend, possibly lover of Jiang Qing. He was the one who introduced her to Mao, and who vouched for her alledged impeccable political credentials.

In Yan’an, Kang played a major role during the Rectification Movement, which was ostensibly intended to instill Mao’s political principles among those who had flocked to base area but who lacked a knowledge of and commitment to the CCP’s ideology. The movement started as an ideological education campaign, but was turned by Kang into a witch hunt for spies and fifth columnists, in which many cases were fabricated against loyal party members who were arrested on trumped-up charges. Many of the intra-elite conflicts that would come out into the open during the Cultural Revolution found their origins here. Yet Mao continued to protect him, even after he had been relieved of his security activities.

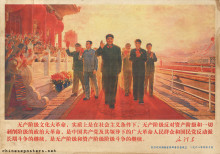

Kang (above, left) was almost invisible during the first years of the PRC. He took to bed, suffering from a variety of undiagnosable illnesses; his addiction to opium may have been a factor. He resurfaced in the mid-1950s, and as a constant supporter of Mao’s policies, he was an important factor in boosting the Mao cult. In the early 1960s, he started his second rise to power. He became a member of the Secretariat under Deng Xiaoping in 1962, and a vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in 1965. By July 1966, he was identified as an ‘adviser’ to the Cultural Revolution Group under the Central Committee, and made a member of the Politburo’s Standing Committee.

Kang is said to have doublecrossed almost all senior leaders during his life, including Jiang Qing. The only exception seems to have been Mao himself. His last triumph was the 1976 campaign to criticize rightist deviationism. The preparations for this campaign, which was aimed against Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, he already had set in motion before his death.

In a secret speech delivered in 1978, Hu Yaobang compared Kang to Feliks Dzerzhinski and Lavrenti Beria. Kang was posthumously expelled from the Party in 1980.

"Problems Concerning the Purge of K’ang Sheng: Hu Yao-pang’s Speech at the Central Party School (Complete Speech)", Issues and Studies (June 1980), pp. 74-100

A Great Trial in Chinese History - The Trial of the Lin Biao and Jiang Qing Counter-Revolutionary Cliques, Nov. 1980-Jan. 1981 (Peking: New World Press, 1981)

David Apter & Tony Saich, Revolutionary Discourse in Mao’s Republic (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1994)

Wolfgang Bartke, Who was Who in the People’s Republic of China (München: K.G. Sauer, 1997)

Wolfgang Bartke, Biographical Dictionary and Analysis of China’s Party Leadership 1922-1988 (München: K.G. Sauer, 1990)

John Byron and Robert Pack, The Claws of the Dragon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992)

Dachang Cong, When Heroes Pass Away - The Invention of a Chinese Communist Pantheon (Lanham: University Press of America, 1997)

Kang Sheng, "On Case Examination Work", Chinese Law & Government 29:3 (1996), 43-47

Donald W. Klein & Anne B. Clark, Biographic Dictionary of Chinese Communism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971)

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao - The Memoirs of Mao’s Personal Physician (London: Random House, 1996)

Lin Qingshan, Kang Sheng waizhuan [Unofficial History of Kang Sheng] (Beijing, Zhongguo qingnian chubanshe, 1988) [in Chinese]

Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Volume III: The Coming of the Cataclysm (Columbia University Press 1999)

Yan Jiaqi & Gao Gao (translated & edited by D.W.Y. Kwok), Turbulent Decade - A History of the Cultural Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1996)

Yang Kelin (ed.), Wenhua dageming bowuguan [Museum of the Cultural Revolution] (Hong Kong: Dongfang chubanshe youxian gongsi, Tiandi tushu youxian gongsi, 1995) [in Chinese]