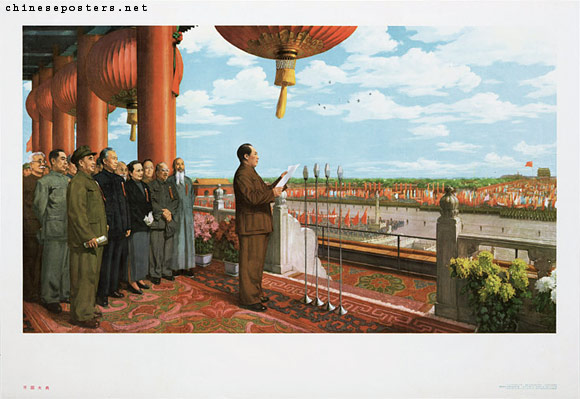

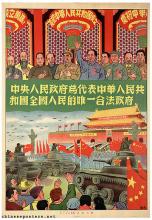

The 1 October 1949 Ceremony and Parade

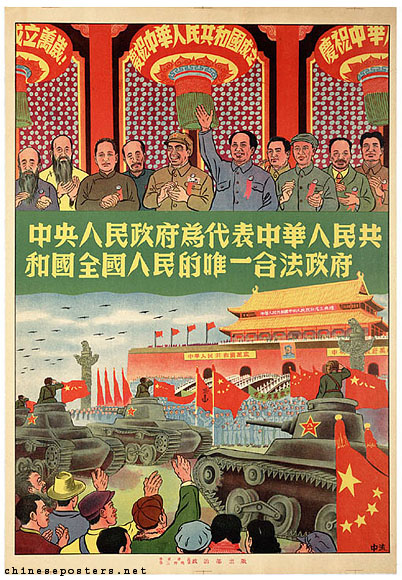

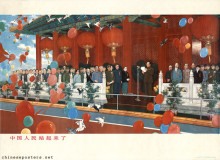

On Saturday 1 October 1949, the inauguration of the People's Republic, known in Chinese as Kaiguo dadian (开国大典), was proclaimed by Mao Zedong atop the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tiananmen Gate, not to be confused with the eponymous Square). For some reason, in most if not all Western reconstructions and recountings of the event, Mao is credited to have uttered at this occasion the words that "the Chinese people have stood up" - and in the various commemorations of the 60th anniversary of the PRC in 2009, this was any different. Mao certainly referred to the liberation of the Chinese people in terms of having stood up, but at other occasions and at other times: in the opening address at the First Plenary Session of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, on 21 September 1949 ("The Chinese people have stood up!"); and in the declaration of this meeting ("Long live the great unity of the Chinese people!", 30 September 1949), with the drafting of which he had been entrusted. During the proclamation at Tiananmen, however, Mao never mentioned that the people had stood up, merely declaring that the People's Republic had been established and proclaiming the instalment of the new Central People's government.

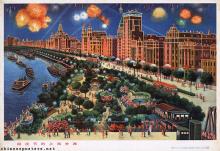

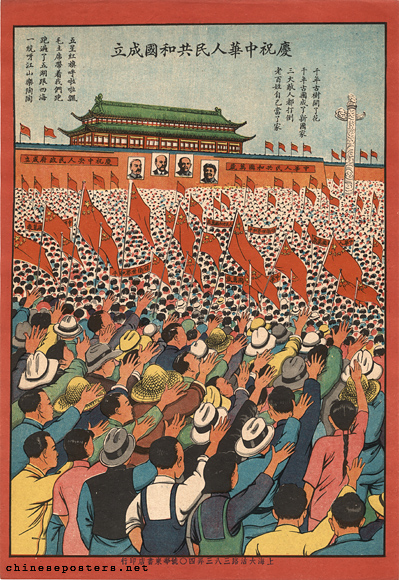

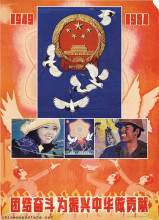

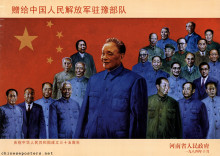

Celebrating the foundation of the People's Republic of China, 1949

This proclamation was followed with a procession that opened with a military parade, with Commander-in-Chief Zhu De presiding. The military under review numbered 16,400 troops, mostly from the infantry and mounted cavalry, small numbers of soldiers with artillery and armored vehicles, and some representatives of the navy and the air force.

In the wake of the soldiers, thousands of cheering civilians marched along Chang'an Avenue. The paraders passed through the East Chang'an Gate, marched over the Square that was still enclosed past the new leaders, and after exiting the venue through West Chang'an Gate, they dispersed in the streets. This grand procession, to which Mao attached great importance, would be repeated twice a year, on 1 May and 1 October.

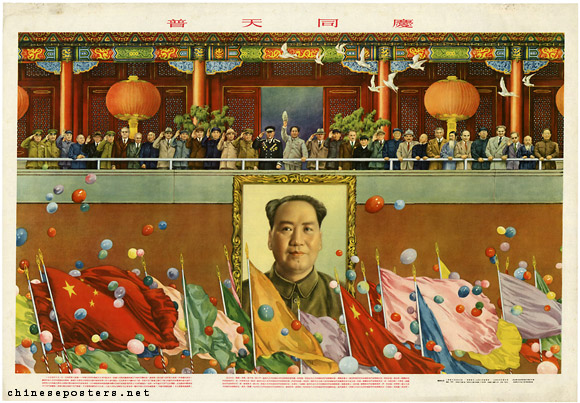

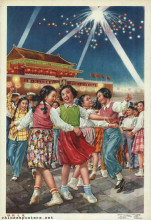

Celebrating the People's Republic of China's National Day, 1950

The procession was led by the Young Pioneers, who represented the future of the nation. They were followed by workers, peasants, government employees, students and literary and art groups. The participants held huge portraits of the national leaders, including Mao and Sun Yatsen. Others played waist drums or danced yangge (秧歌, "rice-sprout songs"), the traditional folk dance originally performed in the open air in rural North China that had been converted during the Yan'an era into a political tool to influence the people and disseminate the new ideals of the Party. The yangge-troupe was made up entirely of experienced dancers from the Department of Literature and Art of the North China University (Huabei daxue). Marchers held up large placards featuring slogans. The main ones were "Celebrate the founding of the People's Republic of China!" "Long live the People's Republic!" "Long live the Central People's Government!" "Long live Chairman Mao!" "Long live the Chinese Communist Party!" "Long live the People's Liberation Army!" Others were more topical and set an agenda of political, economic and diplomatic development for the years to come: "Develop heavy industry; improve national defence!" "There is power in unity!" "Stand forever in solidarity with our great friend the Soviet Union of Socialist Republics and defend the continued peace of the world!"

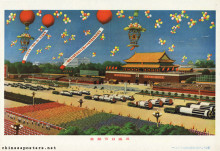

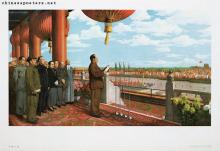

Tiananmen Square in 1949

The Tiananmen Square (天安门广场) that formed the stage upon which the Founding Ceremony was played out, was much smaller than it is today. Hemmed in to the north by a Chang'an Avenue that at the time was only 15 meters wide, and by sections of buildings that used to house the imperial bureaucracy along the east and west, it was a T-shaped space. Already before the parade, the CCP-leadership had decided to create a new symbolic and political center in the capital where people's celebrations of national events would take place. On 31 August 1949, the People's Daily (人民日报, Renmin ribao), the official newspaper, had announced the plans developed by the Beijing Municipal government that would enlarge the square from a capacity of a few tens of thousands to a space to accommodate 160,000 people. In the late 1950s, in commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the PRC, the Square would be expanded even further to reach its current size of 44 hectares, where a million people can assemble.

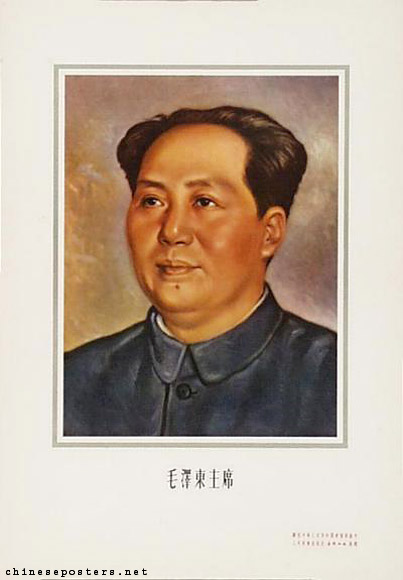

Mao's Portrait

Looming over the Founding Ceremony and the parade was Mao's portrait, hanging on Tiananmen. Mao was not the first Chinese leader to gaze out over the nation. He was preceded by Sun Yatsen, whose likeness appeared above the central gate of Tiananmen in 1929, four years after his death. Once the Republican armies recaptured Beijing (then known as Beiping) from the Japanese in 1945, Chiang Kai-shek's (Jiang Jieshi) image appeared over Chang'an Avenue. Instead of hanging on the wall, as Sun's had done, Chiang's portrait stood above Tiananmen's balcony. Chiang's likeness was replaced by Mao's once the Republic was overthrown. Ten days after the Red Army had liberated Beijing, in February 1949, a painting of Mao's face appeared on Tiananmen for the first time, even before he himself had physically entered the city. For the Founding ceremony in October, a different portrait was installed. This version, painted by Zhou Lingzhao, was based on a photograph Zheng Jingkang had taken several years before in Yan'an. This portrait was soon replaced by another one, executed by a team headed by Xin Mang. This image that presided over the 1 May celebrations of 1950, however, raised questions: Mao was looking upward and seemed to disregard the masses. With that in mind, a fourth portrait was designed by Xin Mang's team that was used for the 1 October parade of 1950; although different from the previous one, Mao still seemed to avoid the viewer's gaze. A fifth version replaced it in 1952. This version, created by Zhang Zhenshi, would remain in place for the next ten years. The portrait that looked down on the Cultural Revolution was designed in 1963 by Wang Guodong. The current version was made by Ge Xiaoguang.

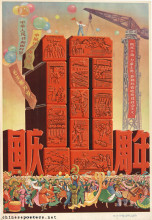

Later parades

The October 1949 parade formed a blueprint for later parades, both the October and May events - and Mao reviewed them all. After 1952, the National Day parade continued with the military part, whereas the May Day parade eliminated the military section and focused on the civilian part, consisting of a ceremonial vanguard made up of workers, waist-drum performers and Young Pioneers. This was followed by a contingent of industrial workers; a contingent of peasants; by teams representing government institutions, schools, merchants and Beijing residents; by the 'Grand Athletic Army' made up of athletes, and finally by the 'Grand Artistic Army' made up of artists. The 1952 parade also saw the introduction of huge models and placards. In 1957, another element was added to this spectacle: the living image, made up of thousands of people facing Tiananmen Gate who held up bouquets of flowers, or colored placards, to form a huge, interchangeable visual pattern.

The Soviet example, already widely admired before the PRC came to be, continued to be widely studied. Soviet military advisers were consulted for the military section. In 1954, a representative of the Beijing Municipal Government was sent to Moscow to study the way in which such events were organized in the Soviet capital. One of the aspects that he reported was that the Soviet parades were characterized by a freer, less strictly organized spirit. Nonetheless, participants in the parades were exhorted to express a passionate spirit. To this end, the Chinese added a tradition following the high point of the parading columns being reviewed by the national leaders: this was the rush of those who ad participated in the various activities one the Square to Gold Water Bridge (金水桥) in front of Tiananmen, to cheer and greet the leaders and their guests. This rush of countless people pushing towards Tiananmen, also known as "Advancing forward in unison" (Yiyong er shang) was not without risk; at various occasions, many people were injured in the melee.

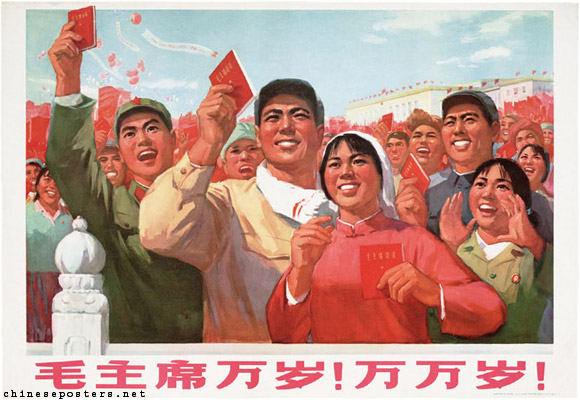

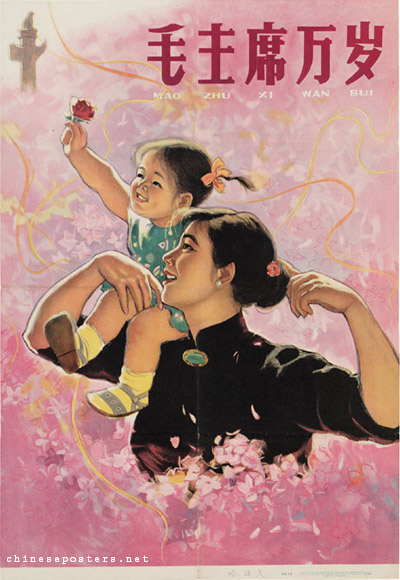

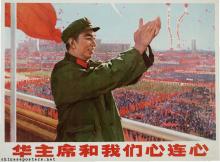

Long live chairman Mao! Long, long live!, 1970

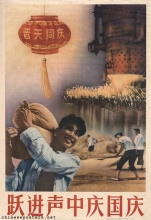

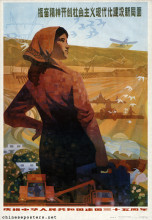

Parades, then, closely followed political developments. The beginning of the Korean War, for example, featured in the slogans of the 1951 National Day parade. In 1957, the slogan "Carry on the Anti-Rightist struggle to the end, and continue to pursue the rectification movement throughout the whole population!" reflected the political preoccupations of the moment. Likewise, the 1958 parade was dominated by Great Leap Forward slogans: "Surpass England and catch up with America; one day is worth twenty years!", "Mobilize the whole population to double steel production!", "Be determined to produce 10.7 million tons of steel!", "With grain as the general-in-command, production will leap foward!", "People's Communes are good!", and "Militarize all the people, defend the motherland and establish militias!". The often tense relations with the different nationalities sharing China's territory and the leadership's desire to portray multi-ethnic unity instead found their way into slogans, dances and groups of participants wearing minority dress.

Long live the great unity of all the peoples of the whole nation, 1957

Political considerations were not only reflected in the various guests flanking the CCP leadership atop Tiananmen reviewing the parades, but also in the portraits that were carried along by the marchers. They gave an indication of who was in favor at the moment and who was out, not only in the international arena, but with regards to domestic politics as well - the portrait of Chen Yun was absent from 1950 until 1954. Portraits of Mao and Sun usually would open the parade, although Mao gradually overshadowed Sun's importance, relegating the latter to the second or even later rows. Following Mao and Sun would be the portraits of Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De and other state leaders. The third row would be made up by the portraits of the ideologues of Marxism-Leninism, i.e., Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. They would be followed by the portraits of leaders of those fraternal socialist countries that were in favor at the time. They could include Kim Il-sung, Ho Chi-minh, and others.

The whole world joins in the jubilation, 1955

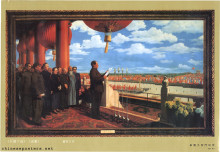

The painting

The celebrated painter Dong Xiwen (1914-1973) was entrusted with artistically recording the first National Day event for posterity. When his oil painting was first unveiled in 1953, it was lauded as one of the greatest paintings ever made by a Chinese. Mao himself said that it showed "...a great country, which is China. Our paintings are unsurpassed if measured against others internationally, for we have our own unique national form". More than half a million reproductions were sold in the three months after the work was unveiled. But less than a year later, Dong had to re-edit his painting as a result of political developments. The person standing to the left of Mao, Gao Gang, had urged the Chairman to retire, had been purged from the Party and had committed suicide as a result. Dong partly replaced him with a potted chrysanthemum.

The Founding Ceremony of the Nation, 1964

When the Cultural Revolution broke out in 1966, Liu Shaoqi fell from grace, and Dong had to redo the painting again, leaving Liu out. In 1973, the "Gang of Four" ordered another version, this one without Lin Boqu who allegedly had opposed Jiang Qing's marriage to Mao in Yan'an. By then, Dong was dying, so two of his students, Jin Shangyi and Zhao Yu, were assigned to assist him; in fact, most of Dong's contributions to this version consisted of consultations. And in 1979, when the Cultural Revolution had ended and massive rehabilitations had started, a reverse edit took place: all those removed from the painting in the past were restored; most of this work was done by Yan Zhenduo, as Jin was abroad. Some now even were sure that a previously unidentifiable figure in the back row now vaguely looked like Deng Xiaoping.

Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung - Volume 5 (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1977)

Julia F. Andrews, Painters and Politics in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1979 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994)

Chang-tai Hung, "Research Report: Revolutionary History in Stone: The Making of a Chinese National Monument", The China Quarterly (2001), 457-473

Chang-tai Hung, "The Dance of Revolution: Yangge in Beijing in the early 1950s", The China Quarterly (2005), 82-99

Chang-tai Hung, "Mao's Parades: State Spectacles in China in the 1950s", The China Quarterly (2007), 411-431

Chang-tai Hung, "Oil Paintings and Politics: Weaving a Heroic Tale of the Chinese Communist Revolution", Comparative Studies in Society and History 49:4 (2007), 783-814

Lu Fang, Zhang Yibing (eds), Dayuebing (大阅兵, Great military parades) (Beijing: Zhongguo sanhuan yinxiangshe, n.d.) (ISRC CN-A60-06-0006-0/V.E)

Yan Geng, "Performing Authority. Mao Zedong's Image at the Founding of the People's Republic", in Burglind Jungmann et al (eds), Shifting Paradigms in East Asian Visual Culture. A Festschrift in honour of Lothar Ledderose (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 2012)

Sang Ye, Geremie R. Barmé, "Thirteen National Days, a retrospective", China Heritage Quarterly, no. 17 (March 2009)

Sang Ye, Geremie R. Barmé, "The First National Day - Two oral interviews", China Heritage Quarterly, no. 18 (June 2009)

Wu Hung, Remaking Beijing - Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005)

Wu Hung, "Television in Contemporary China", October 125 (Summer 2008), 65-90

China prepares for its 60th anniversary

"Replaced eight times: the ‘secret’ of Mao Zedong’s portrait on Tian’anmen", Xin Jing Bao, 28 September 2016

Related series:

Celebrate the 35th anniversary of the founding of the PRC, 1984

![The Founding Ceremony of the Nation [PLA calendar 1985]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/e13-105_0.jpg?itok=WAZRw63q)