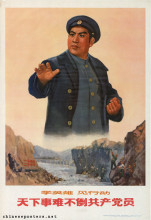

The reform of traditional art was started after the founding of the PRC. These reforms also included the Chinese opera. Many new operas with contemporary and revolutionary themes were created, but not enough to Mao's liking. In the early 1960s, he complained that China's stage was still dominated by "emperors, kings, general, chancellors, literati and beauties", instead of the proletarian heroic models from worker, peasant or soldier stock who could teach and serve the broad masses of the people.

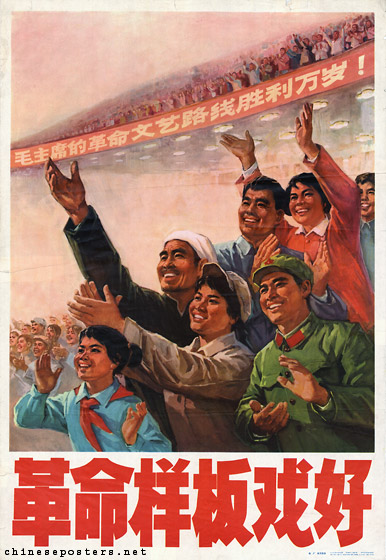

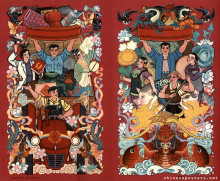

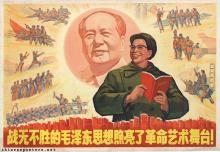

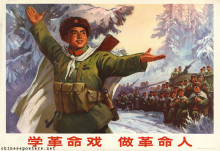

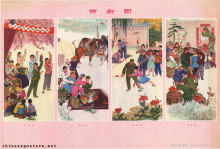

Revolutionary operas are good, 1976

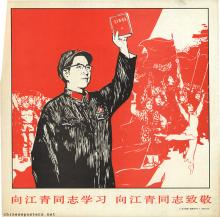

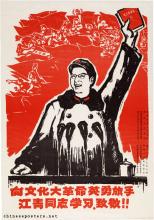

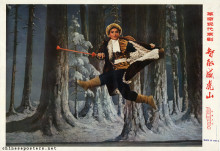

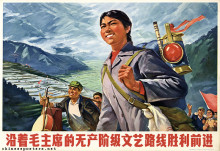

Mao's demands for a new revolutionary national art enabled his wife, Jiang Qing, to start her crusade to dominate the arts world. In 1963, she started with the revision of a number of Beijing Operas on contemporary themes, Hongdengji (红灯记, The Story of the Red Lantern) and Shajiabang (沙家浜, Shajia village). She continued with Zhiqu weihushan (智取威虎山, Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy) and Qixi baihutuan (奇袭白虎团, Raid on the White Tiger Regiment). In the Summer of 1964, these works were performed for the first time at an Opera Festival in Shanghai and by then already were called 'model works' (yangbanxi, 样板戏). In the course of the Cultural Revolution, they became to be considered as part of the 'New Socialist Things' that resulted from the movement.

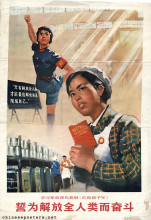

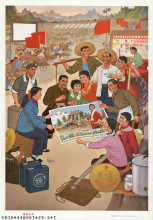

Even children love to study heroes, 1975

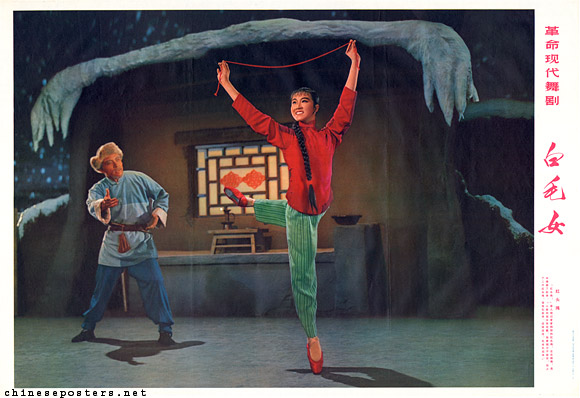

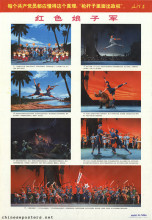

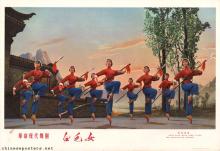

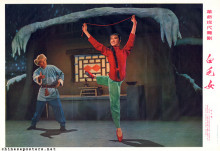

The Festival also exposed her to a number of performances that appealed to her and that she subsequently started revising in 1964-1965. These included Haigang (海港, On the Docks) and a ballet, Hongse niangzi jun (红色娘子军, The Red Detachment of Women). In 1965, she reworked Shaijiabang into a symphony; a year later, she turned her attention to another ballet, Baimao nü (白毛女, The White-haired Girl), based on a yangge (a type of harvest dance) composed in 1944. A second group of nine model works was codified in 1973, but they were not as popular as the earlier eight.

Study revolutionary plays to become a revolutionary, 1972

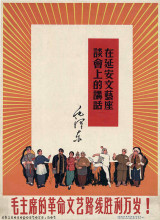

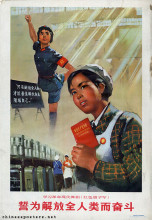

The model works were everywhere. They were broadcast over the radio, made into movies, reproduced on posters and staged all over the country, often reworked for local opera traditions. No matter their form, they had to be identical: model opera scores and production guides were distributed in order to ensure that each performance was the same.

Modern revolutionary ballet--The White-haired girl, 1973

In 1966, Jiang's cooperation with Lin Biao started at the Forum on Literature and Art for the Armed Forces. This provided her with a platform for advocating her model works. The educational effects that the operas were supposed to have owed much to their depiction of the heroes and villains. The heroes had to be gao (高, lofty), da (大, glorious) and quan (全, complete), while the villains had to be base, shabby, ugly and stupid. These effects were further strengthened by the publication of many posters reproducing key scenes from the plays.

Interestingly, Jiang's model works are still very much alive today, if only because the entire population alive during the Cutural Revolution did not hear or see anything else. Songbooks and VCDs or DVDs of most of the model operas are readily available and quite popular with consumers. This is mostly the case with the operas that are set before 1949, when the enemies were the landlords, the Japanese invaders and the Guomindang. Their songs are often sung in karaoke bars and at parties. Their enjoyment is devoid of political meaning, nor is there any lingering negative association with days gone past. Rather, they elicit pleasure and nostalgia.

Paul Clark, "Model Theatrical Works and the Remodelling of the Cultural Revolution", in: Richard King (ed.), Art in Turmoil. The Chinese Cultural Revolution, 1966-76 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010)

Clare Sher Ling Eng, "Red Detachment of Women and the Enterprise of Making 'Model' Music during the Chinese Cultural Revolution", voiceXchange 3:1 (2009), 5–37

Yizhong Gu, "The Three Prominences", in Wang Ban (ed.), Words and their stories -- Essays on the Language of the Chinese Revolution (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 283-303

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1995)

Lu Xing, Rethoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution - The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture and Communication (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2004)

Sheila Melvin & Jindong Cai, "Nostalgia for the Fruits of Chaos in Chinese Model Operas", The New York Times on the Web, 29 October 2000

Barbara Mittler, A Continuous Revolution -- Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013)

Rosemary Roberts, "Positive Women Characters in the Revolutionary Model Works of the Chinese Cultural Revolution: An Argument Against the Theory of Erasure of Gender and Sexuality", Asian Studies Review 28 (2004), 407-422

Rosemary Roberts, "Gendering the Revolutionary Body: Theatrical Costume in Cultural Revolution China", Asian Studies Review 30 (2006), 141-159

Rosemary A. Roberts, Maoist Model Theatre -- The Semiotics of Gender and Sexuality in the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) (Leiden: Brill, 2010)

Roxane Witke, Comrade Chiang Ch’ing (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1977)