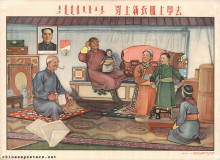

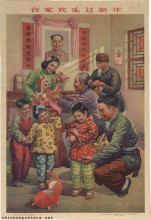

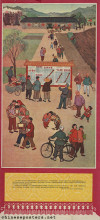

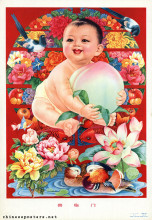

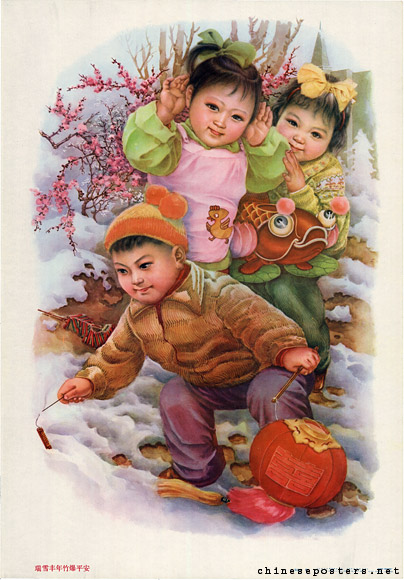

The New Year picture (nianhua 年画) was the most important influence on the propaganda posters produced by the Chinese Communist Party. Employing various elements of folk art and symbolism, these pictures catered to the tastes and beliefs in the countryside, expressing wishes for happiness and good luck. According to the Chinese nianhua specialist Wang Shucun, "During the New Year festival, more than 20 varieties of New Year prints would be stuck on the front gates, doors onto the courtyard, walls of a room, besides a room’s windows, or on the water vat, rice cabinet, granary, or livestock fold. Colourful and floral prints would be everywhere in the house to express the hopes and joy of the festival."

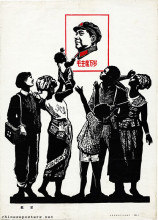

Nianhua derived from ‘paper gods’ and other forms of utilitarian-magic art and made use of symbols that were traditionally and conventionally seen as auspicious, including those for long life, a government career, and wealth. This contributed to their popularity among the people. Often, they featured mythological personages like the Kitchen God, the Door God and the God of Longevity; this turned them into magical charms to drive away bad luck.

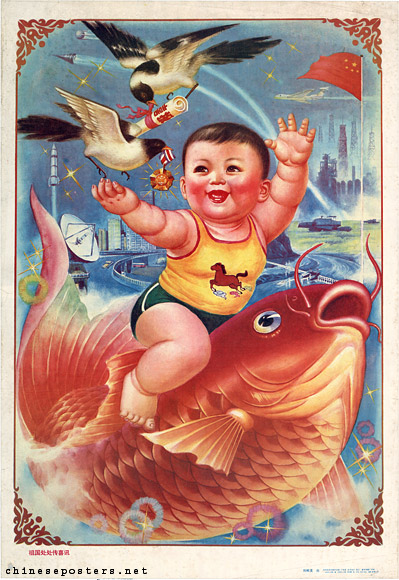

All over the mother country, glad tidings are spreading, 1989

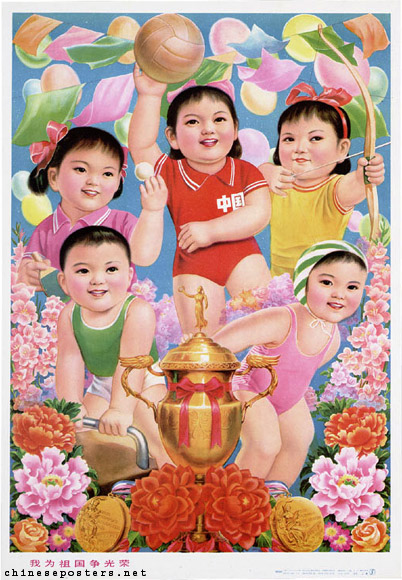

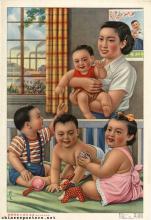

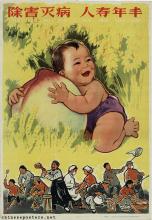

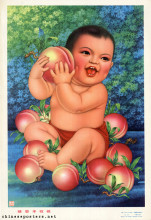

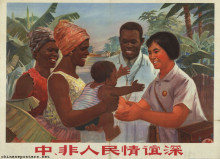

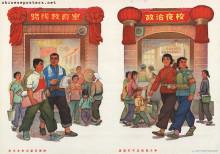

When the CCP appropriated New Year prints for propagandistic purposes in the 1940s, artistic and aesthetic forms were selected that the people had grown accustomed to, filled with new, revolutionary content. But the revolutionary artists looked down on these old forms of popular culture; they were more dedicated to the cosmopolitanism of the cities. They considered traditional art forms to be too intimately connected with the elements of ‘feudal,’ Confucian superstition. Consequently, other types of images replaced them. These still may have featured chubby boys (and girls) but they were permeated with symbols that reflected the correct ideological standpoint.

All strive to become little Lei Fengs, 1978

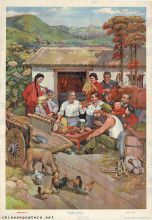

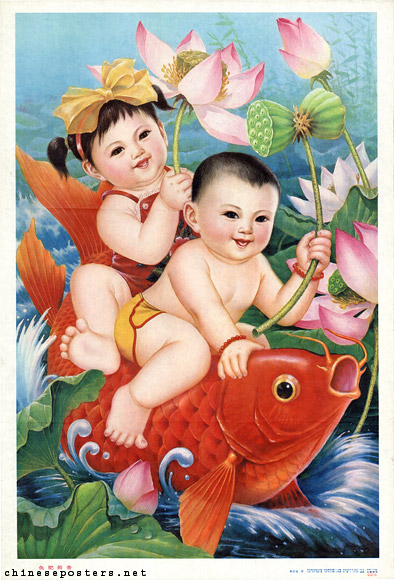

Long Live the Mother Country, 1983

The nianhua produced by the Party were, on the one hand, much too ‘Chinese’ and vulgar to please intellectuals and the urbanites who considered themselves to be more sophisticated. The masses, on the other hand, found them too Westernized and over-simplified to be of great interest for them. ‘New’ nianhua, then, only existed because of the Party, for political reasons. They only replaced traditional nianhua because the CCP succeeded in shutting the latter out by prohibiting their production and distribution. This explains why propaganda posters could be seen in many individual homes in the first decades of CCP-rule.

The fish is fat, the lotus is fragrant, 1987

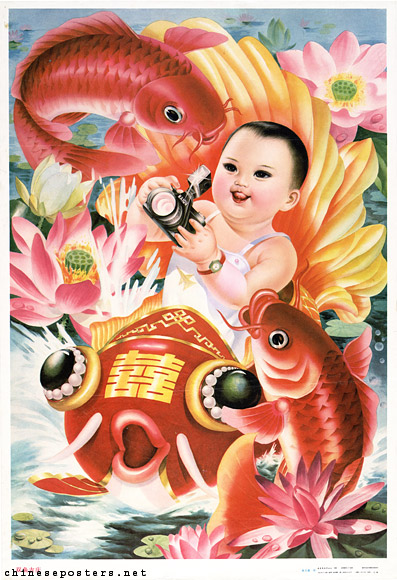

Two fishes are auspicious, 1985

It also explains why other visual materials that contained more traditionally significant symbolic contents, started to replace them as soon as they became available on the free markets in rural and urban areas in the 1980s.

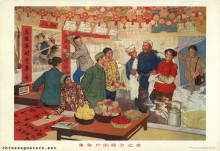

Timely snow, good year, firecrackers, peace, 1982