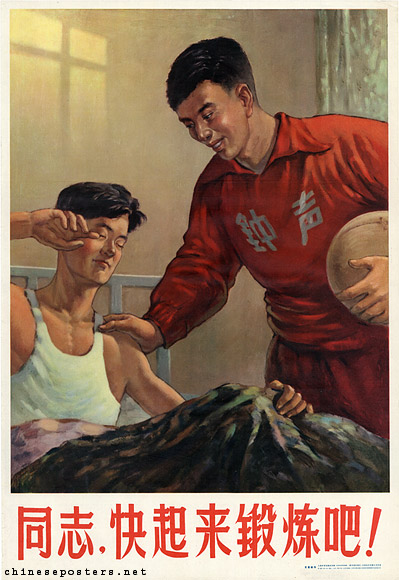

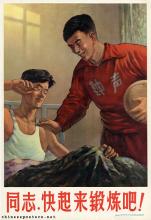

Comrade, get up quickly to train!, 1957

In Imperial China, sports seem to have been an elite activity which was not held in high esteem. Only in the years following the 1911 Revolution, atlethic prowess was seen as a sine qua non for a country aspiring modernity and national strength as much as China was. One of Mao Zedong’s first written contributions to the modernization debate was "A Study of Physical Culture" [体育之研究, Tiyu zhi yanjiu], published in 1917 in the influential journal New Youth [新青年, Xin Qingnian], in which he stressed the benefits of regular exercise and swimming. All his life, Mao would follow his own prescription and swim. The Y.M.C.A. played an important role in the early days of promoting physical education in China.

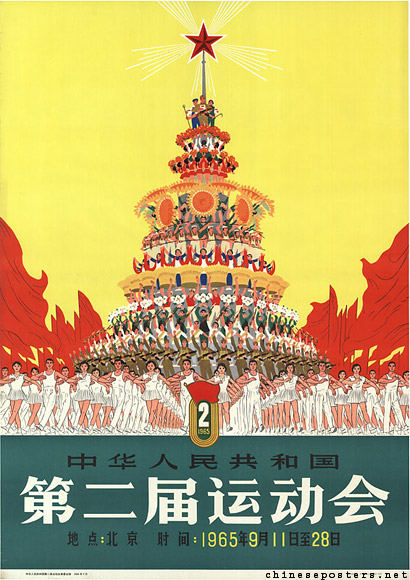

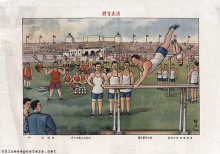

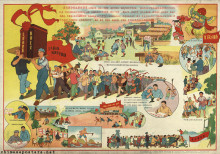

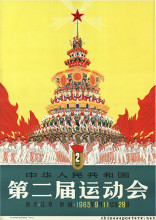

The Second Sports Meeting of the People’s Republic of China, 1965

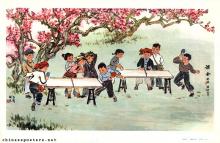

During the Republican period, physical education and sports became a government concern. This resulted in an increasingly spartan and militaristic approach to athletics. China started participating in regional sports meets, such as the Far Eastern Championship Games, which started in 1913. Although not a success in all respects, this participation at least helped to break through traditional localist concerns: people did no longer cheer for their (local) team, but for the national team.

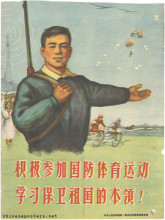

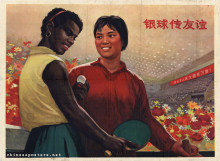

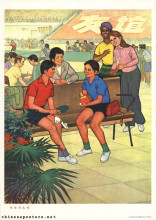

A similar militaristic approach to sports existed in the areas under Communist control. In the Jiangxi Soviet and the base area of Yan’an, activities such as grenade throwing and markmanship were organized, as well as swimming competitions and ice-skating. Table tennis became one of the favorite sports here, despite the fact that it was an American invention. In Yan’an, too, the Department of Physical Education was set up in Yan’an University (1941), and a New Sports Institute organized to study sports theory and to aid in the general development of sports activities. After the founding of the PRC, a stress on physical culture can be found in the Common Program and in the Constitution, which replaced it in 1954.

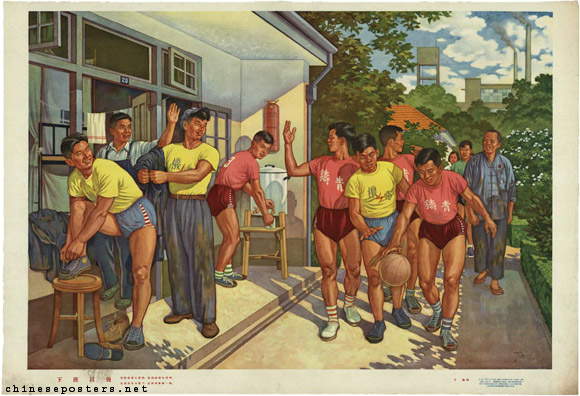

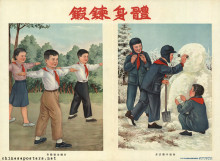

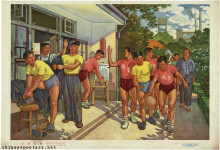

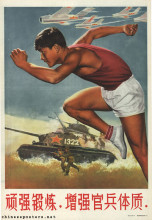

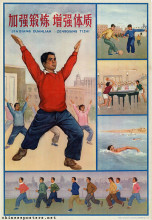

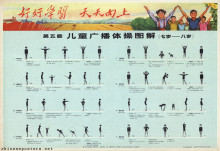

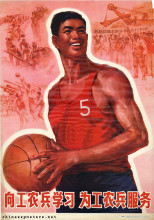

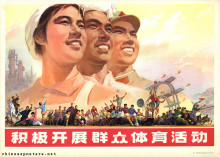

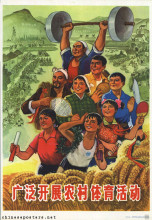

In the propaganda of the early 1950s, the strong and healthy bodies of the workers functioned as metaphors for the strong and healthy working class the state propagated. Training the body, or taking part in sports, was not merely seen as promoting the people’s health, national defense and production, but also as inspiring the collective work spirit necessary for the national unity which was considered a prerequisite to national construction. To achieve this, everybody had to participate in physical education. This mass participation, moreover, added a political component to sports, which explains why ideological training and political study became part and parcel of the training program of Chinese athletes.

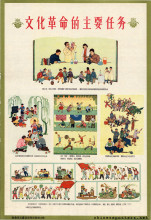

The ideal athlete in the 1960s was unwavering in ideology, kept up his or her physical fitness under all conditions, mastered the game, did not spare him- or herself in training, and went all out in competition, to bring glory to China (wu guo ying, "be tough in five respects"). The call to go all out in competition created tensions with another task ascribed to sports: the fact that it should create unity and cooperation. Under the concept of ‘socialist emulation’, these latter qualities became the main objectives for the sports scene during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

After the Cultural Revolution, when Hua Guofeng and later Deng Xiaoping called for economic reforms to modernize China, sports were once again seen as an important component to bring this about. Promptings to train both body and mind to realize the "Four Modernizations" became a recurring theme in the propaganda posters produced in the 1980s.

When the Chinese women’s volleyball team defeated Japan in the 1981 World Championships, it aroused more enthusiasm than the 1978 decisions that started the modernization program. The victory over the longtime Asian rival inaugurated the revival of Chinese national pride and patriotism that had been dormant during the Cultural Revolution. The team members, who went on to win five consecutive world titles, as well as the Olympics, had realized the long-held dream of erasing China’s label of "the sick man of East Asia" (dongya bingfu).

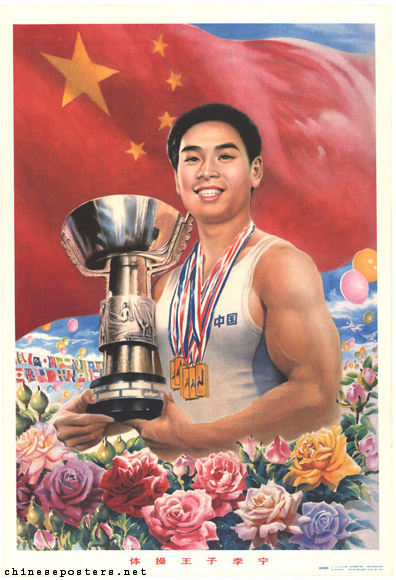

In the 1980s and 1990s, China has become a true competitor in the international sports arena. Chinese athletes hold world and Olympic records in various disciplines. With the opening to the West and the growing ownership of televisions, the Chinese people, moreover, have been presented with a wider choice of sports to participate in, both actively (for example basketball) and passively (for example the widely televised NBA competition as a spectator sport).

The king of gymnastics Li Ning, 1988

On 13 July 2001, the International Olympic Committee voted for Beijing to host the Olympics in 2008. For many Chinese, it was the ultimate confirmation that their country has become a major force in the international sports arena. The Committee’s decision ended a period of intense lobbying, in which at one point the Chinese government stated that hosting the Olympics constituted a human right for the Chinese people.

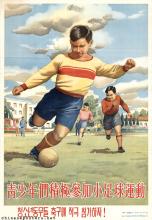

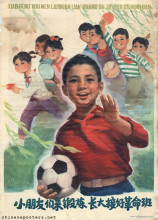

Youngsters energetically take part in youth football sports, 1953

Susan E. Brownell, Training the Body for China: Sports in the Moral Order of the People’s Republic (Chicago, etc.: The University of Chicago Press 1995)

Susan E. Brownell, "The Body and the Beautiful in Chinese Nationalism: Sportswomen and Fashion Models in the Reform Era", China Information Special Issue: The Body in Contemporary China, Vol. XIII, Nos 2/3 (Autumn/Winter 1998/1999), pp. 36-58

John Fitzgerald, Awakening China - Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution (Stanford: Stanford University Press 1998)

Guo Lei, 激励中国:新中国体育宣传画图典(1952-2012) [Inspire China: New China Sports Posters] (Beijing: Contemporary China Publishing House, 2012)

Jonathan Kolatch, Sports, Politics and Ideology in China (New York: Jonathan David Publishers 1972)