The CCP has been prone to laud itself as the champion of women’s liberation. Right from the start, however, the CCP-revolutionaries seemed to have had a dual, and even contradictory approach to questions where women were positioned in the revolutionary process, and this has influenced the way in which women were represented in propaganda posters. On the one hand, there was the demand from the Party that women were to be shown in their entire liberated splendor, as conscious and active participants in the great enterprise of reconstructing (socialist) China. The liberation of the female half of the population had attracted a lot of support for the CCP. Various policies the CCP had experimented with had been codified into legislation after coming to power in 1949. But in the eyes of many women intellectuals at the time, even these measures were not radical enough.

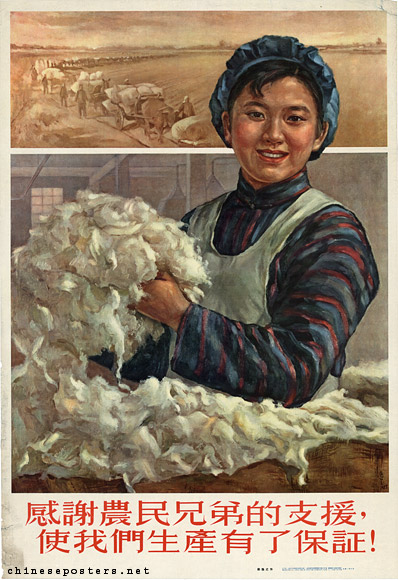

We are grateful for the support of our peasant brothers for ensuring our production!, 1956

Old-fashioned artistic ideas about the representation of women proved to be tenacious. By the early 20th century, a relatively well-established visual tradition had come into existence that treated women as objects that could be consumed by the male gaze. Numerous companies, both foreign and domestic, had settled in the treaty ports and the foreign settlements along the eastern seaboard. The advertising agencies the manufacturers brought with them promoted the use and appreciation of Western art techniques in their advertisements. The advertising posters featured delectable young women, beautiful actresses and popular singers in colorful and tantalizing ‘Shanghai dresses’ (qi pao), endorsing various products, ranging from cigarettes and alcoholic beverages to fabrics and pesticides. The advertisments often were designed by Chinese artists such as Li Mubai, Jin Meisheng and Jin Xuechen, to cater to the specific Chinese sense of aesthetics. Most of them were calendars (yuefenpai 月份牌) that were given away as free promotional gifts and hung up in homes and offices. This commercial printed matter became enormously popular and its influence spread beyond advertising to other types of publications and design practice in general, where it became synonymous with modernity.

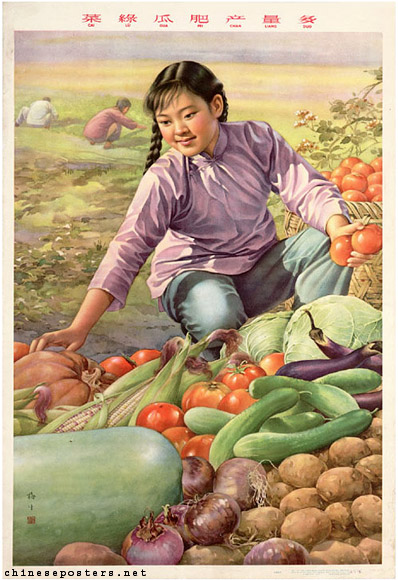

The vegetables are green, the cucumbers plumb, the yield is abundant, 1959

Man works hard, flowers are fragrant, 1962

Even though these materials turned women into objects that served both commercial and titillating purposes, the genre as a whole nonetheless was seen by many as supportive of the demands for the emancipation of women. Instead of treating females as non-entities, as Confucian orthodoxy had prescribed, the posters not merely showed them, but presented them as gorgeously dressed, professional women that radiated an air of self-confidence. To many, these ‘modeng [modern]’ girls were a reflection of women’s search for a separate identity. The supporters of the calendar girls thus included many of the women who themselves were actively involved in the political struggle for women’s liberation.

Her achievement of glory, 1954

With the founding of the PRC, both the theory and practice of the Chinese advertising industry had to change completely. The designers of the commercial calendars, well versed in design techniques and able to visualize a product in a commercially attractive way, were quickly co-opted and incorporated in the various government and army organizations devoted to the production of propaganda posters. But they and their works continued to be regarded with suspicion by the representatives of the new ruling elite. And even though the officials from the cultural bureaucracy that took over had to admit that these designers could make rather acceptable ‘new’ New Year pictures, at the same time they could not refrain from allegations that their works still were marred by numerous political shortcomings.

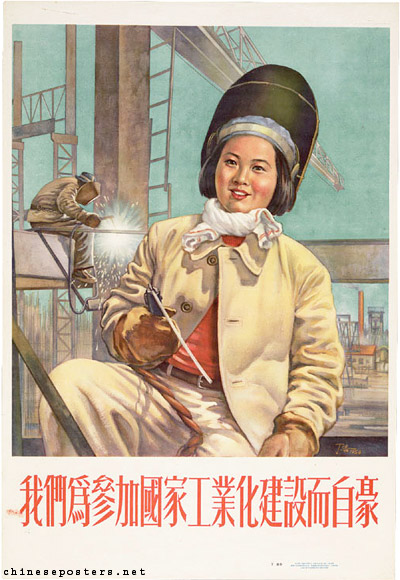

We are proud to participate in the industrialization of the nation, 1954

Chairman Mao gives us a happy life, 1954

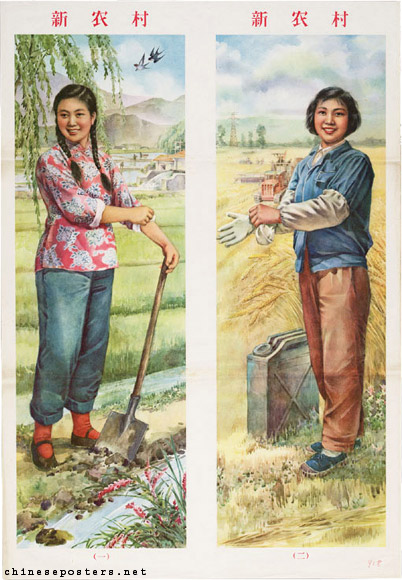

While these cultural authorities insisted that they did nothing more than pass on the correct proletarian viewpoints of (female) representatives of the masses, they usually complained that the artists still lacked the proper ideological standpoint. They acknowleged that the designers dutifully attempted to follow the new rules and regulations pertaining to the arts by producing scenes set in industry or agriculture. In some cases, the artists were accused of tending to depict elegant ‘modern city girls’, with highly patterned blouses and scarves, pale skins and manicured hands, much in the vein of the starlets who had been shown endorsing soap or cigarettes.

New view in the rural village, 1953

These times, however, called for the depiction of peasant or working women taking obvious pride in their work, but whose faces and hands had been marked by unrelenting sunshine and hard labor. In the views of the laboring masses that the art critics allegedly had consulted, such images lacked verisimilitude: nobody in the villages or factories looked like these women. Moreover, no woman dressed in the latest fashions was able to take part in hard physical labor while still looking as spic and span as the poster models did.

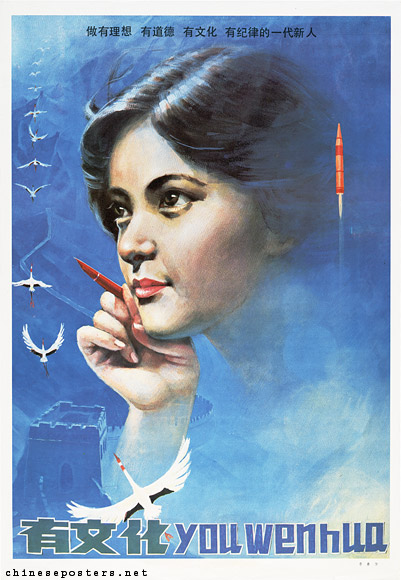

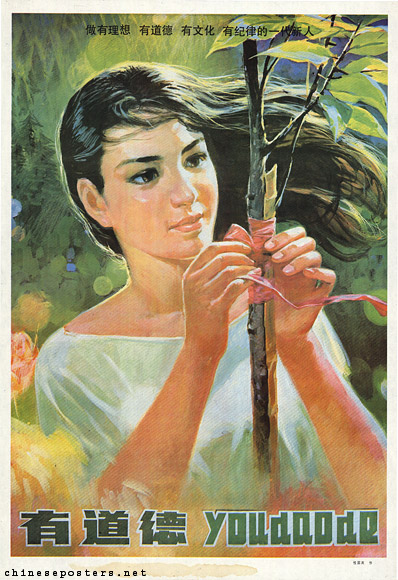

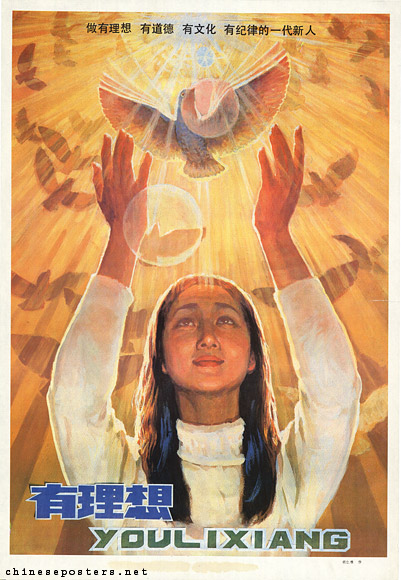

When looking at the practice of depicting women for propaganda purposes, it is safe to say that the ‘pretty girl’ pictures continued to dominate the world of the propaganda poster, with the exception of the periods when high Maoism was the norm. Was this done in an attempt to make the latter’s message more palatable to the population? Or was it simply because such representations could be read as a way of discounting women as revolutionary contenders, as expressions of the widely held belief that women were more interested in matters of clothing and physical appearance than men? Whatever the reason, attractive female forms were used for political propaganda purposes in a manner very similar to commercial advertising, a practice that also has been noted by Chinese writers.

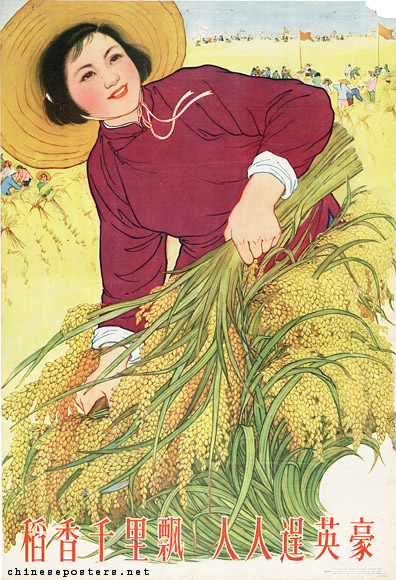

The fragrance of rice floats a thousand miles. Everybody becomes a hero, 1961

Good sisters at the conference of outstanding workers, 1964

The sole exception to the conventional use of female beauty for advertising purposes seems to have been the Cultural Revolution period. During this high tide of puritanism cloaked in a desire for revolutionary purity, only prototypical-masculinized women were permissible. As one of the outcomes of the comprehensive ideology of equality that was adhered to during those days, politics and society considered expressions of femininity as examples of bourgeois behavior and looked down on them. The prevailing moralistic attitude aimed to repress anything that pertained to sexuality and the female body. Women were supposed to work, dress and look like men in clothing that was not supposed to reveal any female curves. With their sturdy features, robust faces and shining eyes, they denoted revolutionary commitment, youth, strength and determination. They were indeed creators and agents of history.

Those holding colored ribbons dance high in the sky, 1976

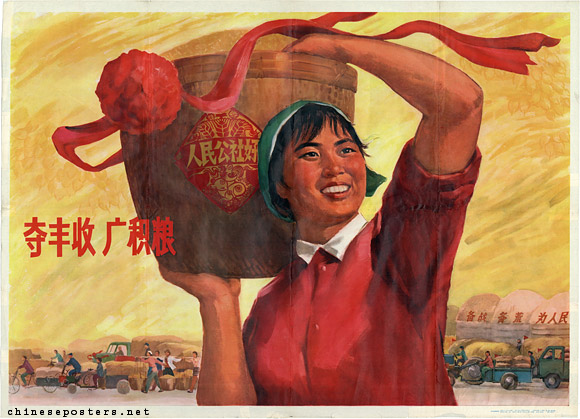

While defining and presenting the broad masses of workers, peasants and soldiers as the proletarian triumvirate that bolstered PRC-society after 1949, this left the question where women would fit in this broader scheme. After all, China could boast of female workers, peasants, as well as soldiers. Posters featuring the revolutionary troika more often than not tended to use male soldiers and workers, with the position of the peasant being taken in by a woman. The theme of the female peasant reverberated with traditional modes of thinking where women functioned as symbols for fertility and fecundity. Without explicitly stressing this aspect, the hope for plentiful harvests thus was included in posters featuring female peasants as well.

Strive for an abundant harvest, amass grain, 1973

On the other hand, many campaigns were designed to address issues that were specific to the liberation of women, or the improvements in their political and social positions, and relevant visual materials accompanied these. Most of the posters designed to publicize the population policy were directed at women. Posters served an explicit educational function as well, showing women new approaches to, and techniques for the various tasks for which they had become responsible. Women frequently appeared as Party secretaries and heads of study groups. But the appearance of women in cadre-functions remained an exception. On higher and even the highest levels of political and administrative power, women were even less visible. Only three women made it to leadership positions at the highest levels, and thus were included in propaganda posters, although for completely different reasons. They were Song Qingling, Jiang Qing and Deng Yingchao.

Warmly love the country, the communist party and socialism, 1983

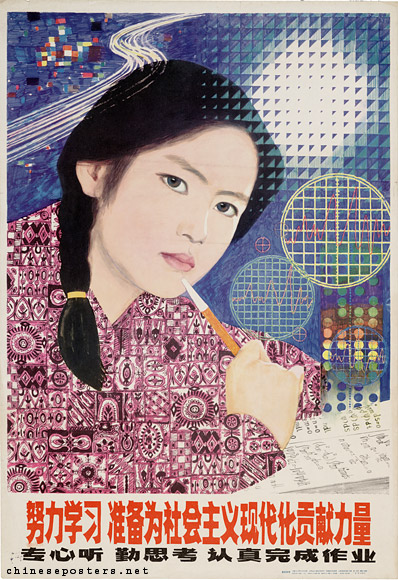

In general, gender boundaries have been redrawn in the 1980s, a process which has continued ever since. In the rapidly changing urban society where cosmetic surgery and liposculpture have become an indispensable part of daily life, and where smartphones and Gucci bags strive for attention and emulation, it made no sense to continue showing a social environment where erst-while politically correct blue, grey or black uni-sex ‘Mao-suits’, chopped hairdo’s and ponytails predominated. These accoutrements of the past have been traded in for more feminine dresses, spiked heels and hot-pants and for hairdo’s that are permed or styled in fanciful ways. Women started to use eyeliner, lipstick, and rouge and as a result, the expenditure on clothing, accessories, cosmetics and hair styling exploded.

Study hard to gain strength to contribute to socialist modernization, 1980

It seems safe to say that the most influential role models for today’s women are no longer presented by posters. Instead, these initially were found in the many lifestyle magazines that have proliferated since the late 1990s. Over the years, television has become the main source of inspiration. As a result, the cheerful, muscular farm girl that was all over the publications in Maoist China has made way for the image of the strong, yet elegant educated career woman. Those living in the countryside are well-served by the endless stream of television and online influencers hammering home the latest dictates in style.

Julia F. Andrews & Kuiyi Shen, "The New Chinese Woman and Lifestyle Magazine in the Late 1990s", in Perry Link, Richard P. Madsen, Paul G. Pickowicz (eds), Popular China - Unofficial Culture in a Globalizing Society (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2002)

John Bayne, "Nostalgia and Aspiration in Popular Chinese Culture: Urban Calendar Perspectives", Bulletin of the British Association for China Studies 1997

Tina Mai Chen, "Dressing for the Party: Clothing, Citizenship, and Gender-formation in Mao's China", Fashion Theory 5:1 (2001), 143-172

Tina Mai Chen, "Proletarian White and Working Bodies in Mao’s China", positions vol. 11, no. 2 (Fall 2003), 361-393

Tina Mai Chen, "Female Icons, Feminist Iconography? Socialist Rethoric and Women's Agency in 1950s China", Gender & History 15:2 (2003), 268-295

Tina Mai Chen, "They Love Battle Array, not Silks and Satins", in Ban Wang (ed.), Words and Their Stories -- Essays on the Language of the Chinese Revolution (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 263-281

Sherman Cochran, Big Business in China: Sino-Foreign Rivalry in the Cigarette Industry, 1890-1930 (Harvard Studies in Business History, 33) (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980)

Sherman Cochran, "Transnational Origins of Advertising in Early Twentieth-Century China", Sherman Cochran (ed.), Inventing Nanjing Road: Commercial Culture in Shanghai, 1900-1945 (Ithaca: Cornell East Asia Series No. 103, 1999)

Daisy Yan Du, "Socialist Modernity in the Wasteland: Changing Representations of the Female Tractor Driver in China, 1949–1964", Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 29:1 (2017), 55-94

Louise Edwards, "Sport, Fashion and Beauty: New Incarnations of the Female Politician in Contemporary China", in F. Martin & L. Heinrich (eds.), Embodied Modernities: Corporeality, Representation and Chinese Cultures (Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, 2006), 146-161

Harriet Evans, "’Comrade Sisters’: Gendered Bodies and Spaces", in Harriet Evans & Stephanie Donald (eds), Picturing Power in the People’s Republic of China - Posters of the Cultural Revolution (Markham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1999)

Harriet Evans, "Marketing Femininity: Images of the Modern Chinese Woman", in Timothy B. Weston & Lionel M. Jensen (eds), China beyond the Headlines (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2000), 217-244

Harriet Evans, "Sexed Bodies, Sexualized Identities, and the Limits of Gender", China Information 22:2 (2008), 361-386

Harriet Evans, "The Gender of Communication: Changing Expectations of Mothers and Daughters in Urban China", The China Quarterly 204 (2010), 980–1000

Ge Lunhong, "A girl goes to work in the countryside during the Chinese cultural revolution (1966–78)", Women's History Review 10:1 (2001), 105-120

Jin Yihong, "Rethinking the 'Iron Girls': Gender and Labour during the Cultural Revolution", Gender & History 18:3 (2006), 613-634

Ellen Johnston Laing, Selling Happiness - Calendar Posters and Visual Culture in Early-Twentieth-Century Shanghai (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004)

Lei Guang, "Rural Taste, Urban Fashions: The Cultural Politics of Rural/Urban Difference in Contemporary China", positions 11:3 (2003), 613-646

Anchee Min, "The Girl in the Poster", Anchee Min et al., Chinese Propaganda Posters: From the Collection of Michael Wolf (Taschen, 2003)

Juliane Noth, "Militiawomen, Red Guards and Images of Female Militancy in Maoist China", Twentieth-Century China 46:2 (2021), 153-180

Claire Roberts (ed.), Evolution & Revolution - Chinese Dress 1700s-1990s (Sydney: Powerhouse Publishing, 2002)

Cheuk Pak Tong, "A History of Calendar Posters", Ng Chun Bong et al., Chinese Woman and Modernity - Calendar Posters of the 1910s-1930s (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing [H.K.] Co., 1996)

Ka-Ming Wu, "Elegant and Militarized: Ceremonial Volunteers and the Making of New Women Citizens in China", Journal of Asian Studies 77:1 (2018), 205–223

Jie Yang, "Nennu and Shunu: Gender, Body Politics, and the Beauty Economy in China", Signs 36:2 (2011), 333-357

Wenqi Yang & Fei Yan, "The annihilation of femininity in Mao’s China: Gender inequality of sent-down youth during the Cultural Revolution", China Information (2017), 1-21

Yi Bin et al. (eds), Lao Shanghai guanggao [Advertisement of the Old Time Of Shanghai (sic)] (Shanghai: Shanghai huabao chubanshe, 1996)

Zhang Yanfeng, "Lao yuefenpai guanggaohua" [Old Calendar Advertisements Posters], Hansheng zazhi [Echo Magazine], Nos 61 and 62 (Taipei, January-February 1994)