Sharing Power with the Chairman

Stefan R. Landsberger, originally published on: http://exhibitions.globalfundforwomen.org/exhibitions/women-power-and-politics/appearance/madame-mao  (International Museum of Women - online exhibition "Women, Power and Politics", 2008)

(International Museum of Women - online exhibition "Women, Power and Politics", 2008)

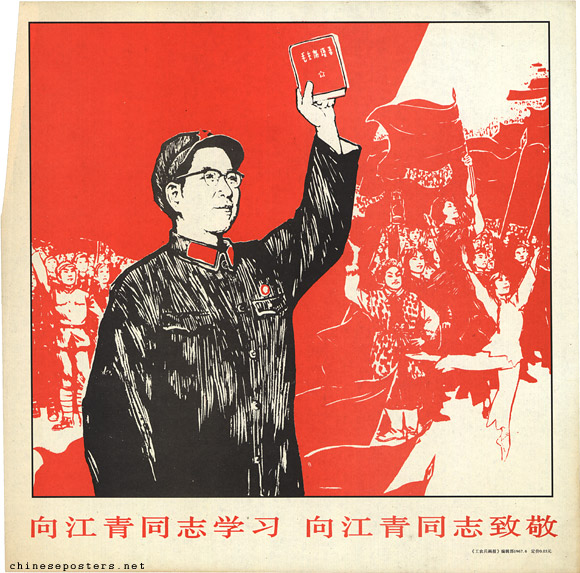

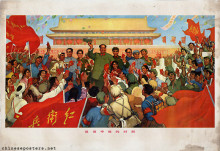

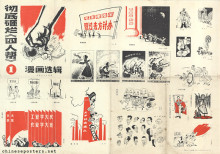

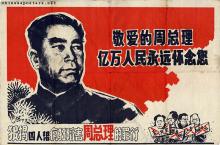

Study comrade Jiang Qing, pay respect to comrade Jiang Qing, 1967

In many parts of the world and throughout history, women have come into leadership positions and been known as "Iron Ladies" because of their powerful husbands. One such figure was Jiang Qing (江青), a woman who came to be called Madame Mao and who, after the Chairman’s death, fell from grace with the Chinese people.

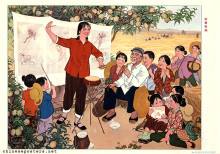

After the People’s Republic was founded in China in 1949, the communist government used poster campaigns to promote women’s liberation. Most of these campaigns focused on women’s role in the economic development of the fledgling Republic. Posters served the explicit educational function of showing women new approaches and techniques for doing various tasks they were now expected to perform. However, persons in positions of real authority continued to be men.

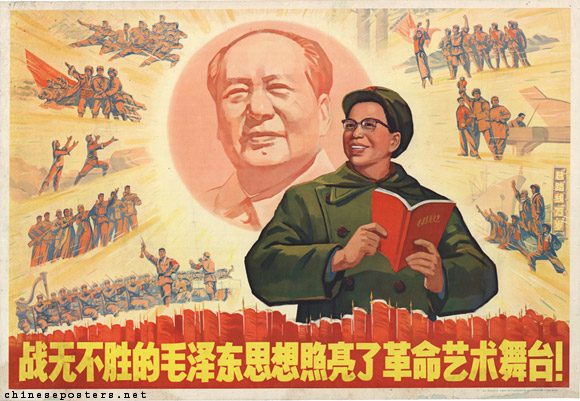

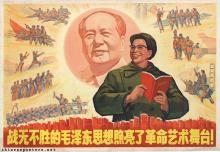

The invincible thought of Mao Zedong illuminates the stage of revolutionary art!, 1969

The most powerful of those men was, of course, Mao Zedong. He regularly appeared in visual propaganda. Women, on the other hand, seldom occupied leadership positions at the highest levels and were seldom represented in posters as political leaders. Jiang Qing, Chairman Mao’s wife, was the most notorious of those rare women who were recognized, and imortalized, as political leaders through illustrations.

Jiang Qing was born in Zhucheng, Shandong Province, in 1914. Assuming the stage name Lan Ping, she became a moderately successful actress in the 1930s in Shanghai. During that time, a close friend introduced her to Mao Zedong. Although Mao was married, he fell in love with the actress and filed for divorce, marrying her in 1939. The Party leadership strongly objected to the divorce and the new marriage, which was Mao’s third. Eventually, the Party was appeased on the condition that Jiang Qing limited herself to the role of a housewife and refrained from playing any role in politics (including making public appearances with him) for the duration of twenty years.

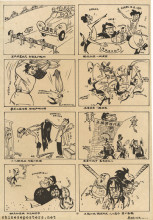

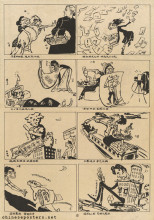

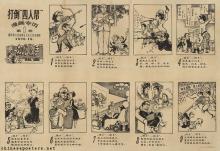

Monkey thrice beats the White Bone Demon, 1977

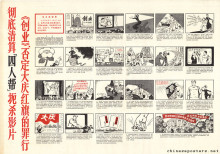

Jiang Qing served as Mao’s personal secretary in the 1940s and was head of the Film Section of the CCP Propaganda Department in the 1950s. In the early 1960s, she made a bid for power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), which resulted in widespread chaos within the communist party.

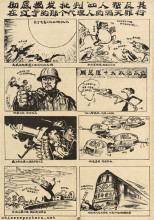

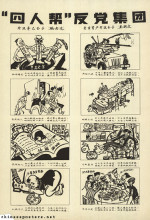

In 1966 she was appointed deputy director of the Central Cultural Revolution Group and claimed real power over Chinese politics for the first time. She became one of the masterminds of the Cultural Revolution, and along with three others, held absolute control over all of the Republic’s institutions.

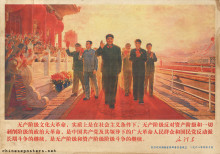

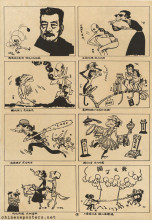

Becoming a powerful figure in her own right, she appeared, for the first time, in political posters. In these posters, she appeared austere and very masculine: her public persona was mainly inspired by the dominant military and proletarian aesthetic. Depicted alongside men, an undiscerning eye wouldn’t be able to single her out. She wore her hair short, further hidden under a cap. She looked much like the Chairman.

When Mao died in 1976, Jiang lost support and justification for her political activities. When she was arrested and sentenced to death, many, if not most, Chinese citizens rejoiced. In January of 1983, her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Suffering from throat cancer, she was released on bail for medical treatment in May of 1991. Ten days after her release, she allegedly committed suicide.