At the end of the First World War, in 1918, China was convinced it would be able to reclaim the territories occupied by the Germans in present-day Shandong Province. After all, it had fought along with the Allies. However, it was not to be. The warlord government of the day had secretly struck a deal with the Japanese, offering the German colonies in return for financial support. The Allies, on the other hand, acknowledged Japan’s territorial claims in China. When it became known in China in April 1919 that the negotiations over the Treaty of Versailles would not honor China’s claims, it gave rise to a movement that might be considered even more revolutionary than the one that ended the Empire.

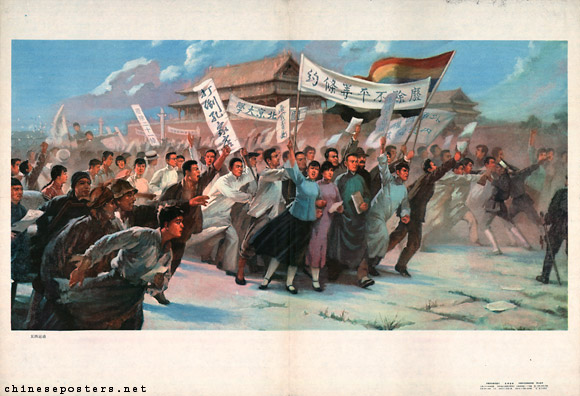

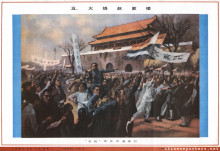

In the course of this May Fourth Movement (五四运动, Wusi Yundong), some 5,000 students from Peking University hit the streets to demonstrate against the Versailles Treaty. But more was at stake than Japan’s grabbing of land. When one considers the 1911 Revolution as a mere regime change, it becomes clear that the numerous popular demands for modernization had not been satisfied yet.

The May Fourth Movement was part cultural revolution, part social movement. On the cultural side, the students had been inspired in the preceding two decades by Western thought, creating a feeling of frustration and dissatisfaction with Chinese tradition. In the intellectual ferment that resulted from this, answers were sought for the questions why and how China had lagged behind the West. The negative influences of traditional morality, the clan system and Confucianism were seen as the main causes. China in its sorry state could only be cured by ‘Two Doctors’: Doctor Science and Doctor Democracy.

At the same time, intellectuals united in the New Culture Movement attempted to make Chinese culture more accessible to social groups beyond the traditional scholar-officials. To this end, they advocated a Literary Revolution, in which wenyan 文言, the ossified system of written language, was to be replaced by a system based on the vernacular, so-called baihua 白话. Hu Shi is one of the scholars identified with this movement, whereas Lu Xun is seen as one of the most prolific practitioners of this type of writing that came into being in the 1920s.

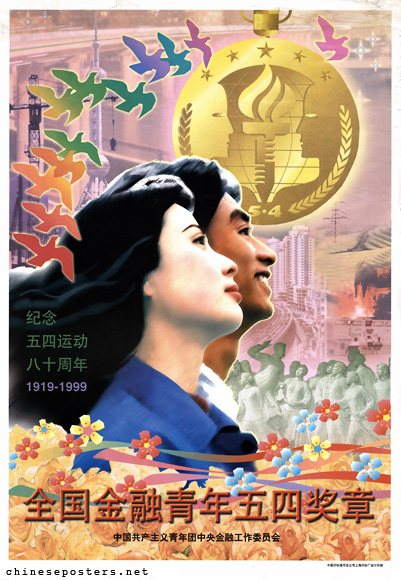

The social aspects of May Fourth consisted of attempts to emancipate the Chinese woman, although this was often limited to movements to bring footbinding to a halt. Nonetheless, in the cities newly liberated women, ‘modeng [modern]’ girls who had been educated, became a loud voice for further changes.

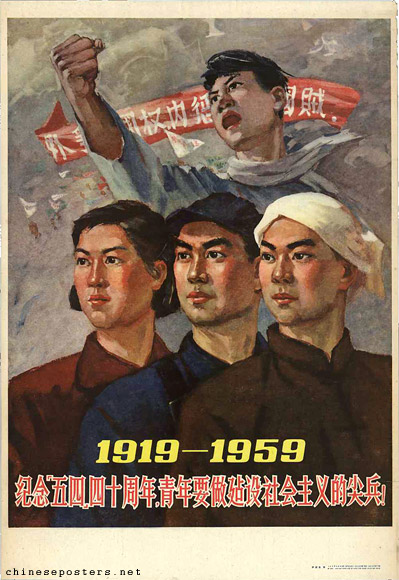

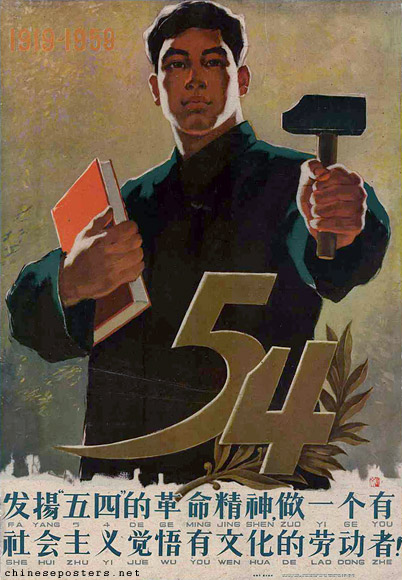

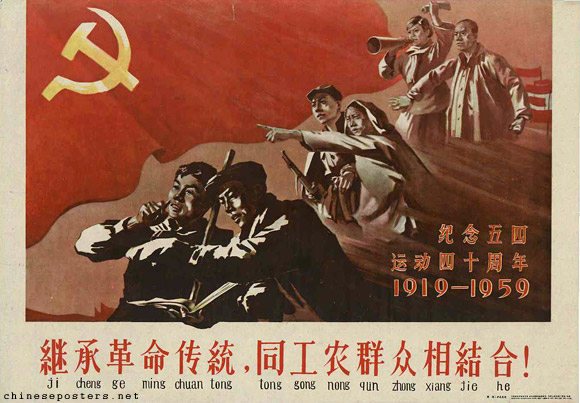

May Fourth is seen as a catalyst for the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. Before 1919, there was hardly any interest in what was happening in Russia. After May Fourth, Marxism was seen as a workable revolutionary ideology for a predominantly agrarian society such as China still was.

Even today, May Fourth functions as a point of reference for China. The Party may interpret the events of 1919 as being brought about by its earliest members, it may turn Lu Xun into the Marxist writer he would refuse to be, the fact remains that May Fourth truly set China on its revolutionary path.

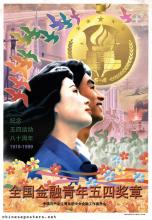

Commemorate the 80th anniversary of the May Fourth Movement, 1999

Chow Tse-tung, The May Fourth Movement: Intellectual Revolution in Modern China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960)

Rana Mitter, A Bitter Revolution: China’s Struggle with the Modern World (Making of the Modern World) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Rudolf G. Wagner, "The Canonization of May Fourth", in Milena Dolezelova-Velingerova, Oldrich Kral, Graham Sanders (eds), The Appropriation of Cultural Capital -- China's May Fourth Project (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 66-120