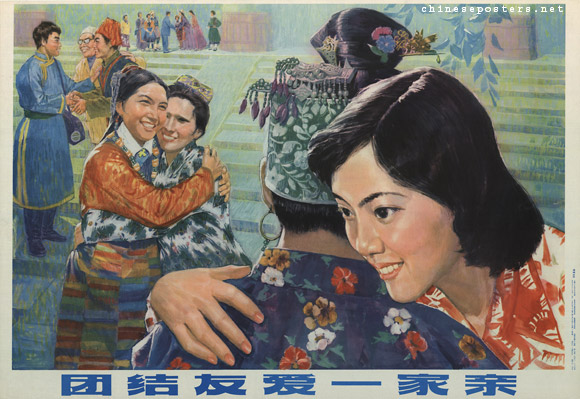

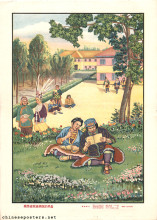

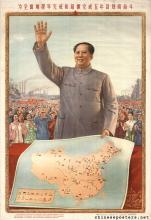

Our country is a united and unified multi-cultural nation, ca. 1982

China is a multi-ethnic state. According to the census conducted on 1 November 2000, aside from the Han Chinese, which account for 91.6 percent of the population, there are 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities, or 'national minorities' in Chinese parlance (shaoshu minzu 少数民族), numbering some 106.4 million people all together. These minorities inhabit approximately 60 percent of Chinese territory, often in the strategically more important or sensitive areas along the borders. The largest minorities are the Zhuang (in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, 15 million); the Manzu, or Manchu (in Northeast China, 9.8 million); Moslems, or Hui (all over China, 8.6 million); Uygur, or Weiwu'er (in Xinjiang Province, 7.2 million); Tujia (Hunan Province, 5.7 million); Mongolians, or Meng (Inner Mongolia, 4.8 million); and Tibetans, or Zang (in Tibet, Qinghai and Sichuan, 4.6 million). The smallest national minorities number only a few thousand members, for example the Gaoshan (Fujian Province) and the Lhoba (Tibet). Many other different ethnic groups (as many as 350) seek official recognition, and at least 15 of them are reported to be officially considered for such recognition.

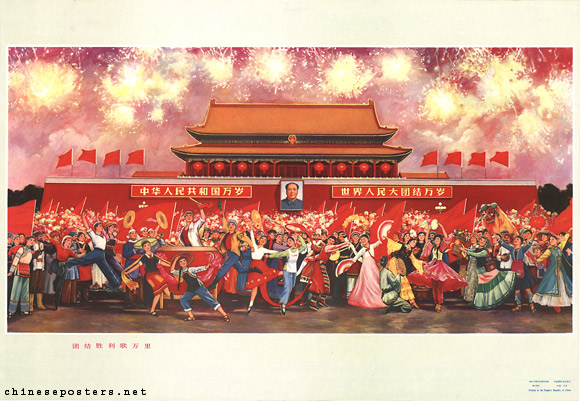

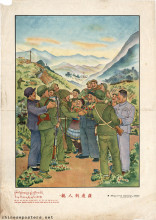

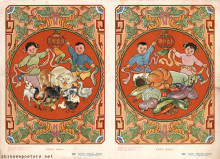

The victory of unity sings everywhere, early 1970s

It is a longstanding myth in China that all peoples inhabiting the territory form a homogeneous whole, the Zhonghua minzu 中华民族, or Chinese nationality. This myth is based upon the premise of a shared descent from the mythological Yellow Emperor, the foundation figure of all Chinese who was purportedly born in 2704 BCE. This legend in turn forms the basis for a (racial) nationalism that implies the existence of primal biological and cultural bonds among China's various ethnic groups. According to scientific research conducted in the early 20th century, the Han nationality was the main branch of all the different population groups in China. This principle forms the basis of China's minority policy. All minority groups ultimately belong to the same 'yellow' race, although they are deemed inferior to it. In other words, the political boundaries of China appeared to be founded on clear biological markers. This line of reasoning has resulted in the official concept that the Chinese people form one big, united family of ethnic groups.

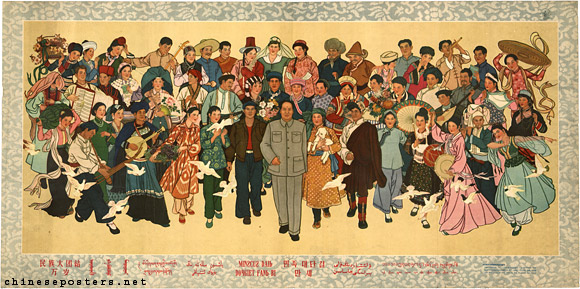

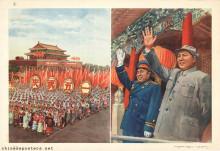

Long live the great unity of all the peoples of the whole nation, 1957

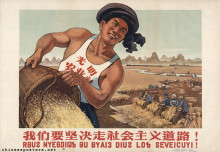

The levels of development of the minorities differ widely, and they are highly heterogeneous both culturally and physically. Some are highly urbanized, while some others practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the not too distant past. Nonetheless, the Han Chinese always have felt that they are on a civilizing mission and have an obligation to help and defend all those peoples that they consider their inferior, backward (luohou 落后) 'younger brothers' (didi 弟弟).

The actual inventory and identification of these minorities only started after the PRC was formally founded. In the Republican period, only five ethnic groups were recognized: Han, Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan and Muslim. In 1950, numerous 'Visit the Nationalities'-teams were sent out to determine what actually constituted minorities, what could be considered as sub-branches of nationalities, or what groups in reality actually belonged to the Han nationality. Initially, the CCP adopted a very broadminded attitude towards the non-Han.

In the early 1930s, viewpoints such as the formation of a federal state granting a high degree of independence to minorities, or even the possibility of secession, were included in the Constitution of the Jiangxi Soviet. In Yan'an, the CCP became aware of the necessity of minority nationality support and appealed to them to support the struggle against Japan. Following Sun Yatsen's ideas about the minority issue, i.e., that all nationalities in China were equal, had the right to self-determination and would be part of a free and united republic of China, Mao asserted that their spoken and written languages, their manners and customs and their religious beliefs had to be respected.

The nationalities' policies as phrased in the Common Program of 1949, the provisional Constitution that predated the first Constitution promulgated in 1954, actually favored those groups that had a minority status. One result of this was that the first national census, which took place in 1953, reported no less than 400 minorities. In the period 1953-1956, all these groups that asserted a separate nationality status were determined by applying the definitions that Josef Stalin had defined as markers for nationality status. Thus, they had to share a common language, a common economic base, a common psychological makeup (or culture), and a common territory. As this was not always applicable in China, the markers of historical origin, migration history and agreement by the people themselves were added. By applying these definitions, 54 minorities had been officially recognized as such by 1957. Over the years, the identification work would continue. The last people to be recognized, the Jinou, was added in 1979.

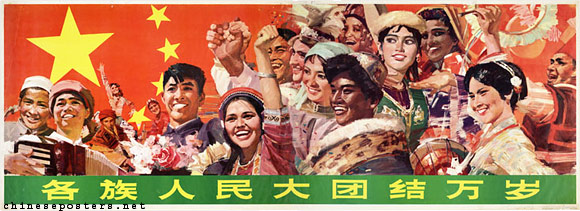

Long live the great unity of all nationalities, 1960

It is important for an ethnic group to be officially recognized as a national minority. Minority peoples are given special treatment, including a license of moral, cultural, religious and social liberties which the state does not wish to grant to the majority of the population. These liberties include a family planning policy which does not restrict the number of children; the right to retain certain marriage patterns and traditions of conducting one's sexual life; and the right to engage in various forms of religious practices which are otherwise considered "superstitious". On the political level, being a minority may lead to a level of limited autonomy that leaves room for local decisions on education, finances, culture and religion. It is also important for the state to officially recognize a national minority. It has set up an apparatus for registering and administrating ethnic differences, allotting different rights to different ethnic groups. This enables selective social control and formal structures for political inclusion or cooptation of groups which otherwise might alienate themselves from the system.

Embroidering a silk banner with words of gold, 1978

The cooptation of minority interests has been an important factor in forging national unity, in merging all 56 national individual minorities into one Chinese nation. Another element has been the presentation of the best and most pliable elements of nationality culture in terms of this unity. In the media, national dances, music and songs are woven together in a mixture which implies unity while at the same time emphasizing the individual characteristics of each nationality.

Long live the great unity of the people of all nationalities, 1979

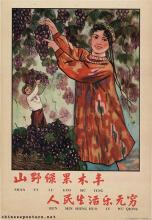

Although it can be said that these elements have saved certain minority practices from extinction, they at the same time have had a stiffling effect on the development of these peoples. The 'noble savages' in their colorful national costumes, fellow countrymen yet so alien, living in their traditional dwellings and compounds, engaging in traditional songs and dances, have become important components of a thriving tourist industry that caters to both foreign and Chinese visitors. Sadly enough, the minorities themselves usually are not sharing in the profits.

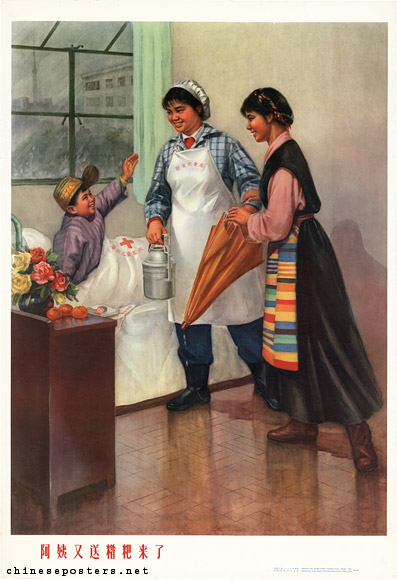

Auntie has even come to bring tsampa, early 1970s

Despite the official recognition of separate ethnic groups, there exist both an ingrained prejudice and a local negative opinion among the Han Chinese towards these minorities, something that is inevitably noted by the minorities themselves. The Chinese mistrust and bias towards non-Han as barbarians are age-old phenomena. Some of this is discernible by the appellations of the minorities in Chinese: in many cases, the characters that were used for the official name of a minority originally contained the pictorial element of 'dog' or 'pig'. Although this has been changed in most cases, minorities are still not completely accepted and integrated. Many Han Chinese continue to see minorities as childlike persons, wearing colorful costumes and spending the day with song, dance and other typical local practices.

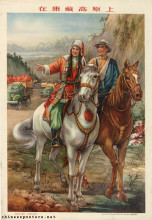

Showing loving care, early 1970s

Their portrayal often can be considered derogatory and colonial, but this is a practice that extends to imperial times, and is not specific to the PRC. Moreover, many myths exist about the alleged carefree sexuality that is celebrated by the minorities. That may also explain why minority representatives on posters are usually females. When males are represented, they invariably are shown while engaged in non-threatening behavior. Minority peoples that have no strong outward physical resemblance to the Han Chinese, for example the Dai, or who are considered to be more primitive, tend to be more easily eroticized than groups such as the Manchu and the Koreans.

An impregnable bulwark on the grasslands, 1974

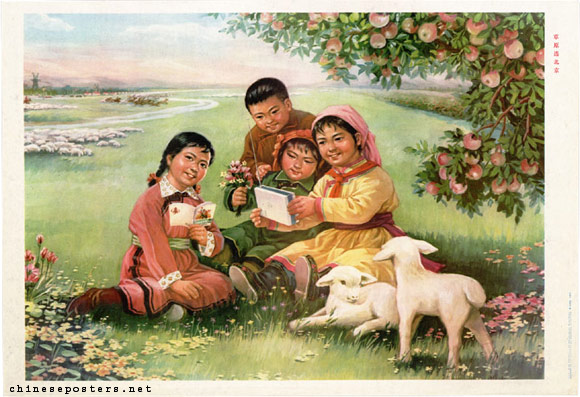

That the state felt the need to instruct the minorities is quite obvious from the propaganda posters produced in the first three decades of the PRC. They all show happy minorities enjoying the fruits of socialism, but guided by the Han. Another indication of the ethnic unity that existed was provided by the posters dedicated to mass scenes extolling the virtues of the PRC or of Mao. They usually featured token Tibetans, Miao, Dai, Khazaks and others minorities in national dress, acting as icons for the ethnic diversity of China.

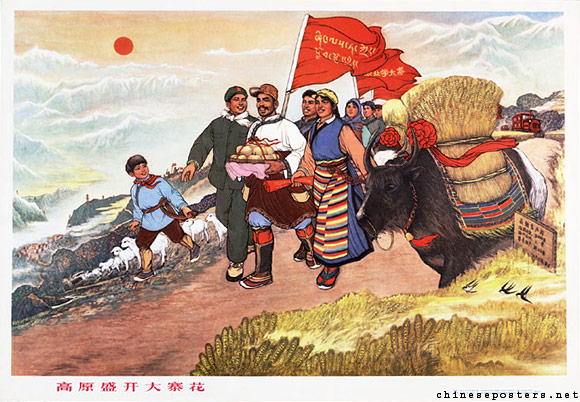

The flower of Dazhai is in full bloom on the plateau, early 1970s

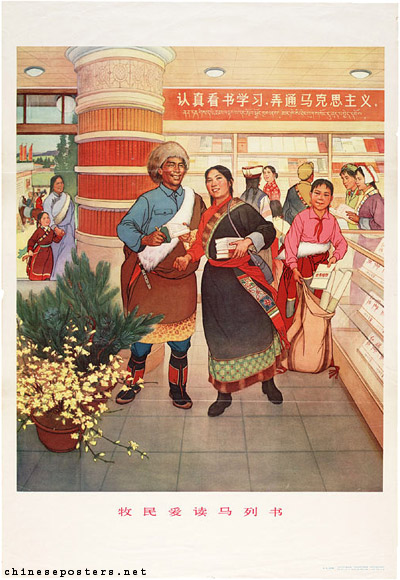

No minorities appeared in posters in the first half of the Cultural Revolution, but they were reintroduced after 1969, and in large numbers. The same period witnessed the publication of posters with bi- or multi-lingual titles, or slogans. Next to the text in Chinese, a translation was provided in a number of cases in Mongolian, or Uygur, Tibetan, or one of the languages used among the peoples living in the Southwest. This was a departure from the previous state of affairs, when the use of most of the minority scripts that had been (re)constructed so painstakingly in the 1950s, was restricted. These bi- or multi-lingual posters generally address themes relevant for relations between the Han Chinese and the minorities. Examples are images of Mongolian herdspeople holding books ("herdspeople love books by Marx and Lenin"), Tibetans accompanying Han soldiers ("The blossom of Dazhai blooms on the plateau"), Mongolian elderly following the example of Lei Feng, etc.

Herdspeople love to read books by Marx and Lenin, 1976

The spirit of Lei Feng is handed down generations, 1975

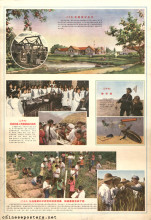

The late 1970s witnessed the production of a number of posters depicting the minorities' joy with the concrete fruits of development, such as wireless radios and electricity. Similar considerations were responsible for the posters that represented the hospital treatment of minorities by Han nurses, or the fact-finding tours in factories, where fraternal Han workers showed them around. Aside from the much-vaunted unity, other messages are made very clear. Thanks to the Han Chinese, minorities now not only have access to health care, but also are taken care of by Han medical personnel. Thanks to the Han Chinese, minorities have access to radios and electricity, and in the near future even will operate sophisticated factory equipment themselves.

The grasslands are connected with Beijing, 1977

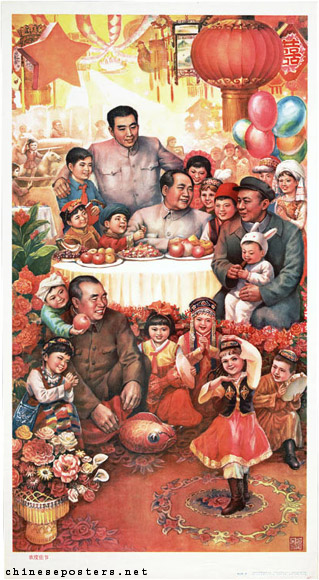

After the Cultural Revolution officially came to a close in 1976, large numbers of minorities were put on display on posters. This was part of Hua Guofeng's attempts to become a true successor of Mao. To accomplish this in the public gaze, minorities were recruited in a major way to indicate that an unprecedented level of unity existed, as all peoples supported the leadership change, and had boundless faith in Chairman Hua. The predominance of Mongols, Kazaks and Tibetans changed slightly in favor of other groups.

Chairman Hua is our intimate friend, 1978

Only after 1978, when Deng Xiaoping had returned to power, the leadership openly admitted that its minority policy had failed to improve conditions in most minority areas and had, in fact, even had been responsible for a general deterioration. Moreover, it acknowledged that during the Cultural Revolution in particular, incidents of violent devastation and severe oppression had taken place in minority regions. Autonomous regions with large numbers of minority populations, such as Tibet and Xinjiang in particular, had suffered greatly and they became the areas where large-scale restorations were undertaken.

Celebrating a festival with jubilation, 1983

The only examples in which artists continued to use representatives of the minorities, in their colourful garb, were those in which the founding fathers of the CCP, such as Mao, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi and Zhu De, were depicted, in order to perpetuate the image of one happy extended family of peoples. In line with the more urban orientation that propaganda took in the 1980s, the minorities' propaganda appeal has clearly diminished.

Anne-Marie Brady, “'We Are All Part of the Same Family': China’s Ethnic Propaganda", Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 41:4 2012), 159–181

Uradyn E. Bulag, "Models and Moralities: The Parable of the two ‘Heroic Little Sisters of the Grassland’", The China Journal, No. 42 (1999)

Uradyn E. Bulag, "Seeing Like a Minority: Political Tourism and the Struggle for Recognition in China", Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 41:4 (2012), 133–158

Uradyn Bulag, "Nationality / 民族", Made in China Journal (4 September 2020)

Flemming Christiansen & Shirin Rai, Chinese Politics and Society - An Introduction (London etc.: Prentice Hall 1996)

Frank Dikötter, "Reading the Body: Genetic Knowledge and Social Marginalization in the People’s Republic of China", China Information, vol. 13:2/3 (1998-1999), 1-13

Dru C. Gladney, "Representing Nationality in China: Refiguring Majority/Minority Identities", Journal of Asian Studies 53:1 (1994)

Gregory E. Guldin, The Saga of Anthropology in China - From Malinowksi to Moscow to Mao (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1994)

Thomas Heberer, China and its National Minorities - Autonomy or Assimilation? (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1989)

Hsieh Jiann, The CCP’s Concept of Nationality and the Work of Ethnic Identification Amongst China’s Minorities (Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1987)

Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, National Minorities Policy and its Practice in China (Beijing, 1999)

James Leibold, "More Than a Category: Han Supremacism on the Chinese Internet", The China Quarterly 203 (2010), 539–559

Li Yu, Representations of Ethnic Minorities in Chinese Propaganda Posters 1957-1983

Colin Mackerras, "What is China? Who is Chinese? Han-minority relations, legitimicay, and the State", Peter Hays Gries & Stanley Rosen (eds), State and Society in 21st-century China - Crisis, Contention, and Legitimation (New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004)

Thomas S. Mullaney, "Ethnic Classification Writ Large -- The 1954 Yunnan Province Ethnic Classification Project and Its Foundations in Republican-Era Taxonomic Thought", China Information 18:2 (2004), 207-241

Barry Sautman, "Myths of Descent, Racial Nationalism and Ethnic Minorities in the People’s Republic of China", Frank Dikötter (ed.), The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan - Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (London: Hurst & Company, 1997)