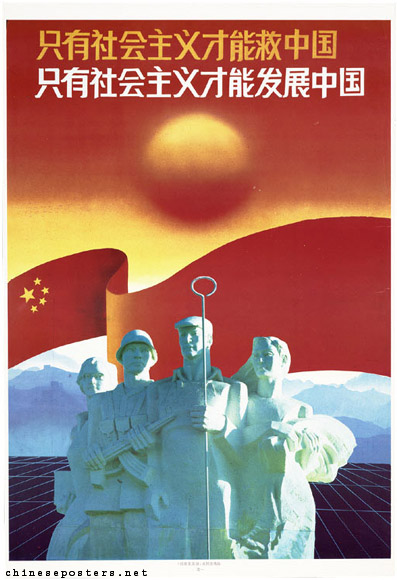

When looking at the PRC, the concept of political reform seems to be non-existent. But when Deng Xiaoping had the Four Modernizations adopted in December 1978, a measure of political reform that would flank the developments in the economy was quite high on the agenda. Aside from attempts to delink Party and government, which were closely associated with Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, most reform initiatives in the political sphere stranded in the face of resistance from Party conservatives. Once Hu and Zhao had been removed from the scene, and in particular after the Tiananmen Incident of June 1989, political reform became a taboo. The poster reproduced below, entitled "Only socialism can help China, only socialism can develop China" and showing the official answer to the 1989 demonstrators’ Goddess of Democracy, nicely encapsulates the political atmosphere that existed in China in the early 1990s.

Only socialism can help China, only socialism can develop China, 1989

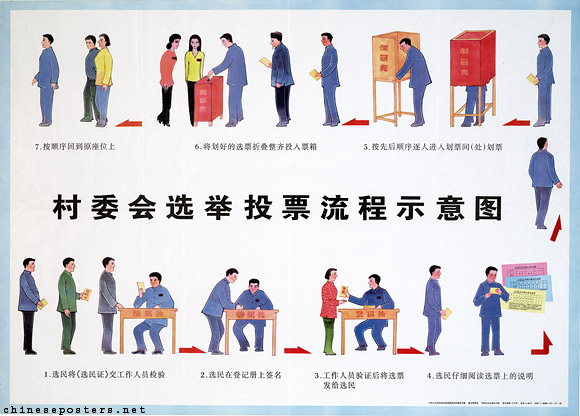

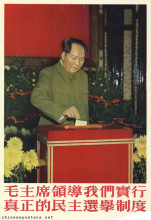

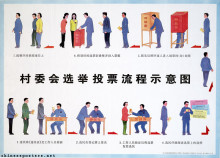

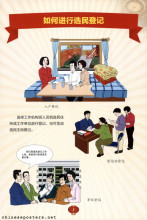

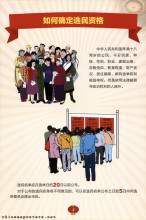

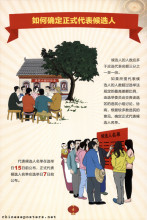

Despite the prevailing sentiment, some measure of political reform has been slowly taking shape. In 1982, the Constitution for the first time legitimized villagers’ self-government. By 1987, the provisional Organic Law on Villagers’ Committees was enacted by the National People’s Congress. On the basis of this legislation, the Ministry of Civil Affairs started experimenting with direct, competitive village elections in that same year. The initiative did not derive from a sudden love for democratic procedure, but rather from the necessity to reestablish Party control in the countryside in the aftermath of the destructive policies of the Great Leap Forward (1958-1961) and the Cultural Revolution (1967-1976). The idea was that unpopular policies (birth control, taxes) would be easier to accept when they were carried out by locally elected rather than appointed officials.

Officially, the Party can veto nominees, thus ensuring that politically reliable cadres are elected. At the same time, the fact that villagers now have the opportunity to choose their own leaders seems to have given them a sense of accountability and greater control over their own lives. Representatives are no longer elected on the basis of their political purity, but whether they can improve the economic conditions in the village. Until early 1999, such elections were strictly limited to the villages, although elections on higher administrative levels have been promised for a number of years already. Such an election did take place once, on the next higher level of the township, and was immediately declared illegal by the Party while it lauded the use of democratic procedures. After the initial official criticism, however, movements are underfoot to indeed expand the principle of democratic elections at the township level. It may be a slow process, but things are definitely changing: in Spring 2000, it was announced that the process of direct elections would be expanded to the neighborhood residents’ committees in the urban areas. In 2005, Premier Wen Jiabao reaffirmed his and the Party’s commitment to the election process.

Merle Goldman, "In Rural China, a Brief Swell of Electoral Waters", The Washington Post, 21 February 1999, p. B02

Thomas Heberer, "Urban Elections in the People's Republic", IIAS Newsletter, No. 39 (December 2005), p. 15

Jiang Wandi, "Fostering Political Democracy from the Bottom Up", Beijing Review, March 16-22, pp. 11-14

Daniel Kelliher, "The Chinese Debate over Village Self-Government", The China Journal, No. 37 (January 1997)

Lianjiang Li, "The Two-Ballot System in Shanxi Province: Subjecting Village Party Secretaries to a Popular Vote", The China Journal, No. 42 (July 1999)

Building of Political Democracy in China, Government White Paper, October 2005