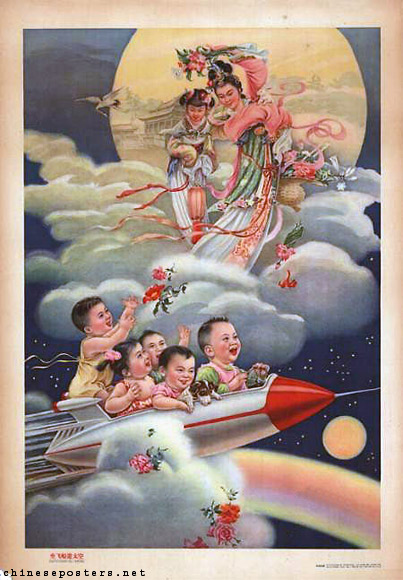

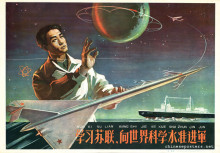

Roaming outer space in an airship, 1962

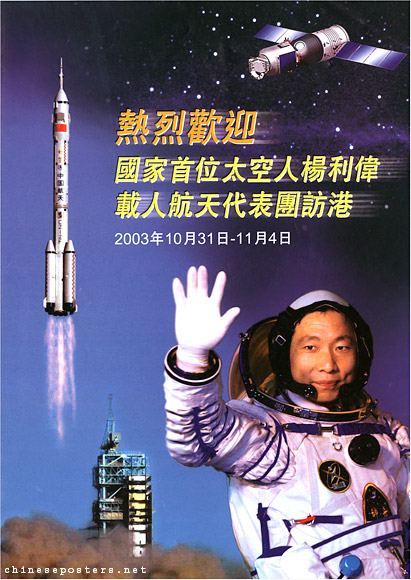

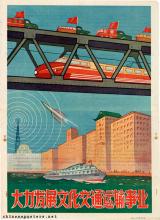

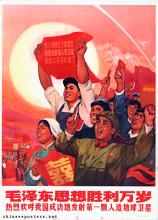

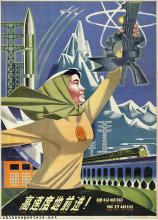

The succesful launching of the Shenzhou V (神舟五号), the Divine Vessel, on 15 October 2003, with taikonaut Yang Liwei (杨利伟) on board, marked a giant leap forward in the Chinese space program that saw its origins in the 1960s. With this result, China joined the club of space-travelling nations that previously had been limited to the United States and the Soviet Union/Russian Federation. A previous Chinese launching  , in 1970, had already brought a satellite into orbit that endlessly broadcast Dongfang hong (东方红, The East is Red), not the national anthem, but probably one of the best known Chinese tunes, eulogizing Mao Zedong. The success of this mission was solely ascribed to the genius of Mao Zedong Thought, which had guided the scientists and workers. In reality, Qian Xuesen (1911-2009), a rocket engineer formerly attached to the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, U.S., who had been expelled in the 1950s for suspected Communist sympathies, designed China's first missiles, earning him the accolade of being the father of the space program.

, in 1970, had already brought a satellite into orbit that endlessly broadcast Dongfang hong (东方红, The East is Red), not the national anthem, but probably one of the best known Chinese tunes, eulogizing Mao Zedong. The success of this mission was solely ascribed to the genius of Mao Zedong Thought, which had guided the scientists and workers. In reality, Qian Xuesen (1911-2009), a rocket engineer formerly attached to the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, U.S., who had been expelled in the 1950s for suspected Communist sympathies, designed China's first missiles, earning him the accolade of being the father of the space program.

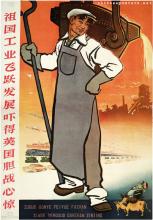

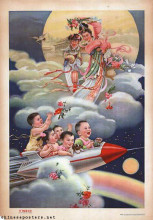

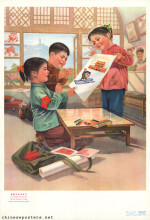

Little guests in the Moon Palace, early 1970s

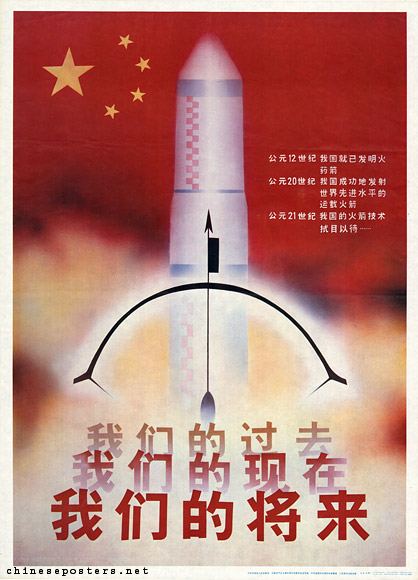

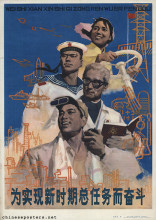

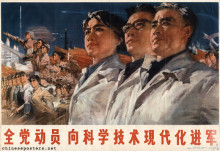

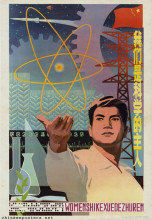

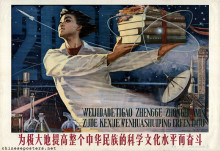

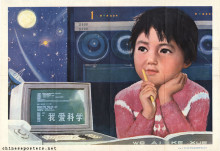

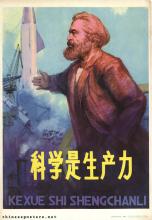

In the early 1970s, the Chinese space program was brought to a halt as a result of the political turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. After Deng Xiaoping returned to power in the later 1970s, the program was revived in the 1980s. Clearly, the military industrial complex also benefitted greatly from this development, thus enabling the People's Liberation Army to demonstrate how well it responded to the political demands to modernize. Space also appealed to the popular imagination, as can be seen from the relatively abundant use of space-related imagery in posters published in the 1980s and 1990s.

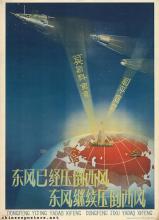

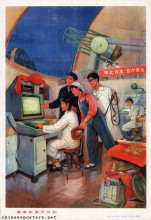

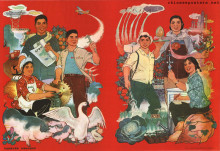

Our past, present and future, 1987

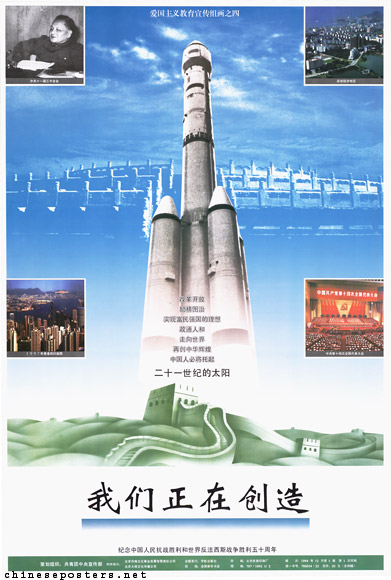

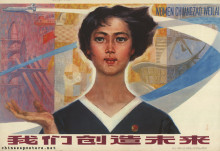

We are in the process of creation, 1994

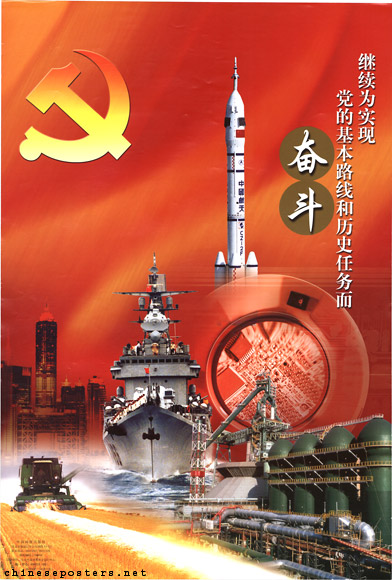

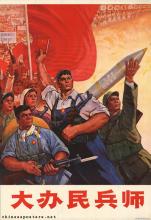

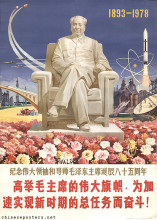

Under Jiang Zemin, however, the program, now named the 921 project, really took off in the 1990s. Successes in space exploration are very much seen as results of the CCP's support for advanced scientific projects that is part and parcel of his theory, the "Three Represents". The Party has appropriated the space mission rather as another justification for its continued rule, and attempts to use it even further to fan patriotism. In this patriotic discourse, space activities are another indication that demonstrate that China has shaken off the humiliation it has suffered in the past at the hands of the Western imperialist powers and is becoming a nation once more to be reckoned with.

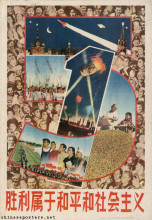

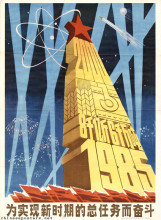

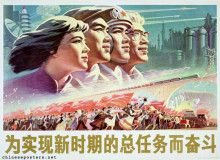

Continue the struggle to realize the basic strategy and the historic duty of the Party, 2002

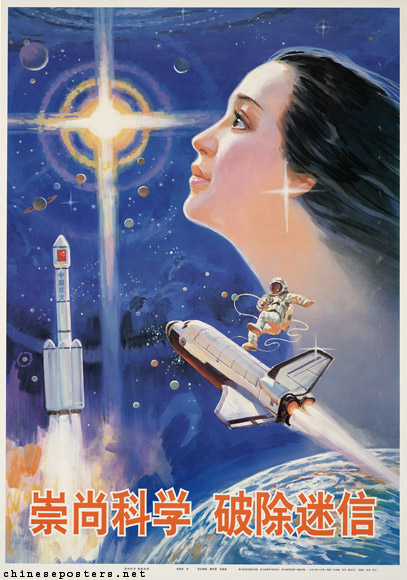

Moreover, space exploration and scientific research in general are part of the Party strategy to combat specific religious behavior that it sees and terms as superstition. Even in materials aimed at Falun Gong adherents, space imagery has been used in an attempt to bring them back into the fold.

Uphold science, eradicate superstition, 1999

Aside from the numerous benefits for the CCP's legitimacy, military developments and further space exploration, it stands to reason that the Shenzhou-mission will be exploited endlessly for propaganda purposes. Colonel Yang, for example, immediately was turned into an instant hero. According to media reports, 10.2 million sets of commemorative stamps have been issued. Unfortunately, no commemorative posters seem to have been published! In their absence, I reproduce some earlier artists' impressions of Chinese space travel below.

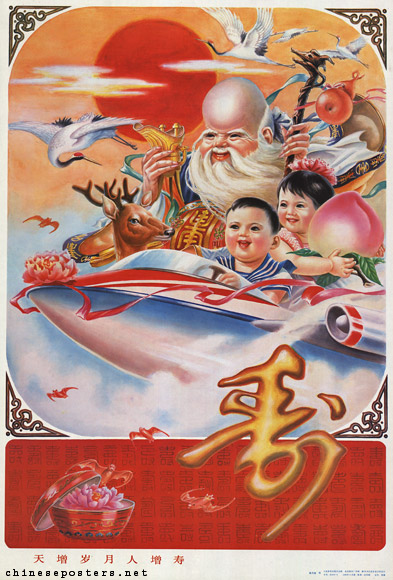

Heaven increases the years, man gets older, 1989

Aside from the political use of the space mission, its success really has struck a chord with the people. They feel proud and consider China's joining of the space family as another indication that the country is regaining some of the splendor and importance it had during its imperial past. As a result, a number of Chinese companies have included the Chinese conquest of space in their printed and television advertising. Jianlibao, a sports drink, already featured a Chinese taikonaut walking on the moon in one of its television commercials broadcast in early 2003.

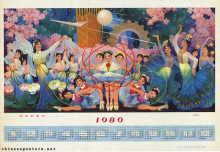

Bringing his playmates to the stars, 1980

On 12 October 2005, China launched its second manned spacecraft, the Shenzhou VI, for a multi-manned, multi-day mission. Colonels Fei Junlong (mission commander) and Nie Haisheng (mission operator) embarked on a flight that took four days, during which they undertook a number of scientific experiments. The launch was part of a more encompassing space program that includes space walks, the docking of a capsule with a space module and the launch of a permanent space lab. Moreover, in 2006, China started with the selection of women astronauts.

Leonard David, Shenzhou Secrets: China Prepares for First Human Spaceflight

Matthew Forney, "Great Leap Skyward", Time Asia, vol. 162, n. 12 (29 September 2003)

Eric Hagt & Matthew Durnin, "Space, China's Tactical Frontier", Journal of Strategic Studies 34:5 (2011), 733-761

Michael Sheehan, "‘Did you see that, grandpa Mao?’ The prestige and propaganda rationales of the Chinese space program", Space Policy 29 (2013), 107-112

Stacey Solomone, "The Culture of China's Space Program: A Peking Opera in Space", Journal of Futures Studies 11:1 (2006), 43-58

Stacey Solomone, "China’s Space Program: the great leap upward", Journal of Contemporary China 15:47 (2006), 311–327

Zheng Zhongyang, "The origins and development of China’s manned spaceflight programme", Space Policy 23 (2007), 167–171

Biography of Yang Liwei (in Dutch)

China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology

China National Space Administration

Chinese Academy of Space Technology

China's Space Activities--PRC Government White Paper of 22 November 2000