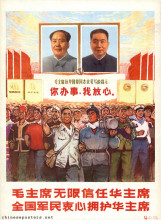

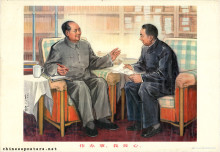

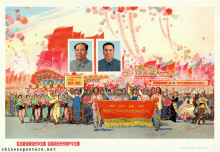

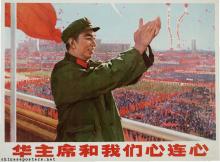

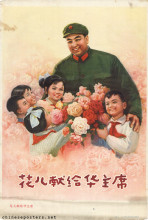

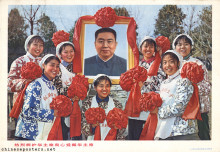

Chairman Hua's heart and ours beat as one, 1977

Hua Guofeng (华国锋, nom de guerre of Liu Zhengrong, 1920/1921-2008) was born in Jiaozheng county, Shanxi Province, in 1920 or 1921. As Mao Zedong's handpicked successor, he brought the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) to a close and prepared China for the process of economic reform and modernization that is usually associated with Deng Xiaoping's 1978 proposals.

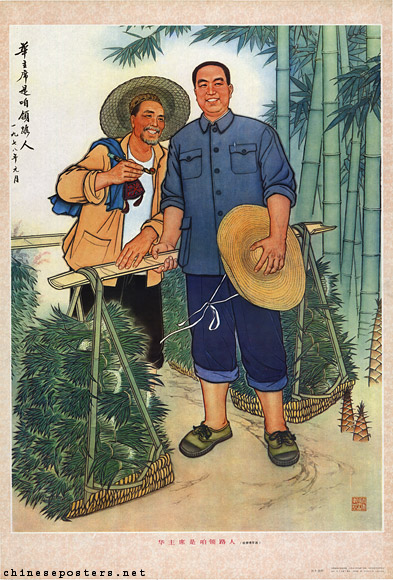

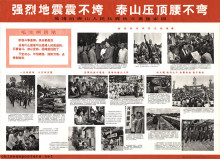

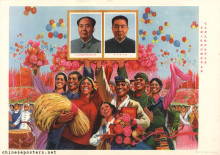

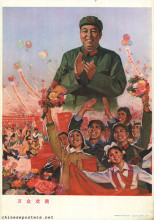

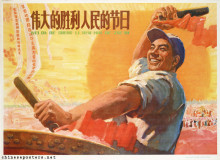

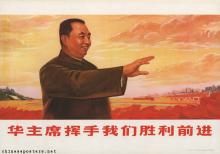

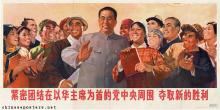

Chairman Hua shows us the way, 1978

Although the information concerning Hua's youth is scant, the details about his political career are well-documented. In the late 1930s, he joined the anti-Japanese guerrilla forces in his native county. By the mid 1940s, Hua had already become propaganda chief of the county Party committee. In the following years, he occupied ever higher rungs on the career ladder, taking on such responsibilities as the political commissariat of the county armed forces detachment. In 1949, he joined the People's Liberation Army troops moving southward in their liberation of China. After his arrival in Hunan Province in late 1949, he continued his bureaucratic and military advancement. Of great importance for his later career was his posting in Xiangtan, the native district of Mao Zedong. By personally overseeing various projects there (including an irrigation project in Shaoshan, Mao's native village), he was able to catch Mao's attention in an early phase.

By the early 1970s, Hua had not only become both first secretary of the Hunan provincial Party Committee and political commissar of the Canton military region, he had also joined the Party Central Committee. On the national level, his star rose rapidly. By 1971, he had become a "leading cadre" of the State Council with the rank of Vice-Premier. After his election to the Politburo in 1973, he became minister of public security in 1975. As recent history has shown time and again, this is an ideal starting point to prepare one's claims for the highest position of leadership. When Premier Zhou Enlai died in January 1976, Hua was his logical replacement. In the following months, with Mao's health deteriorating rapidly, a scramble for power started between Jiang Qing and her Gang of Four on the one hand, and Hua and his supporters on the other. In the end, Hua emerged victorious.

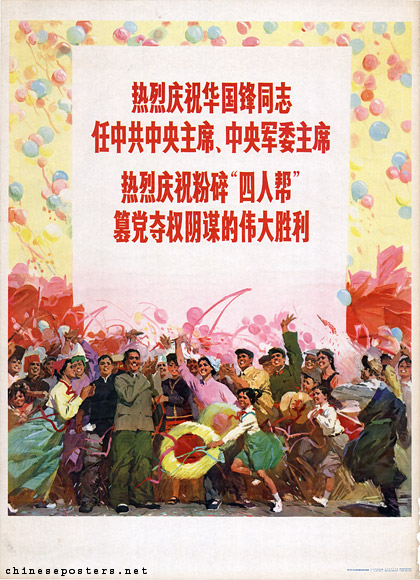

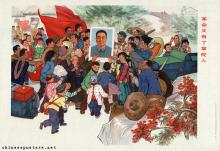

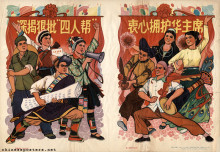

On 6 October 1976, within a month after Mao's death, Hua had the Gang of Four arrested. This bold move was supported by various old Party cadres and Army men, including Ye Jianying, Li Xiannian, Xu Xiangqian and Nie Rongzhen; Mao’s former bodyguard Wang Dongxing also played a major role. After the elimination of the Gang, the country rejoiced.

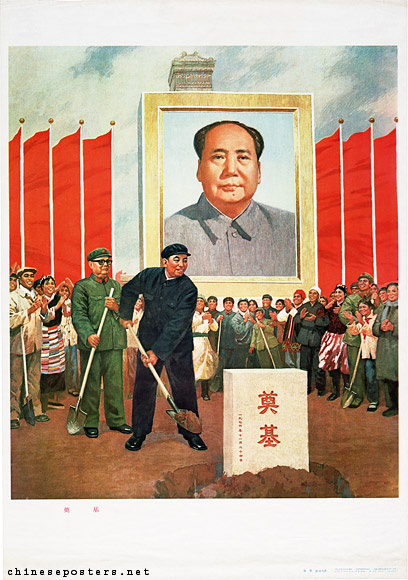

Once the decision was made that a mausoleum was to be constructed to house Mao's embalmed remains, Hua again was able to dominate much of the attention devoted to this event. This ranged from posters recording the laying of the foundations of the mausoleum to the moment the structure was officially opened for the masses to pay their respects to the departed leader.

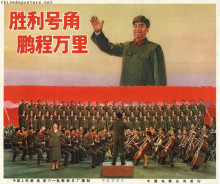

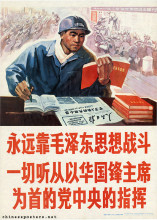

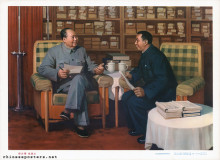

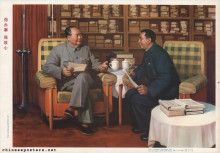

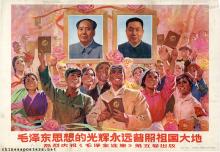

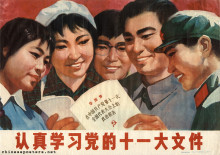

With Hua Guofeng in power, the styles and themes that had been instrumental in propagating Mao and his ideas continued to dominate Chinese propaganda art, even though Mao had died and the Cultural Revolution had been formally called to a close in 1976. Hua not only tried to take over Mao's political legacy by uncritically adopting most of his policies by stating that "We firmly uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and we unswervingly adhere to whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave". He further presented himself as the officially legitimated interpreter of Mao's ideological behest by acting as the editor of the fifth volume of the Selected Works of Mao Zedong, which appeared in 1977. Moreover, he also tried to groom his image as much as possible to resemble Mao, even adopting his predecessor's swept-back hairdo.

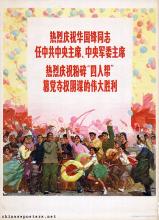

A personality campaign was started to promote him as the ultimate leader, by which he claimed part of Mao's position as object of reverence: both Mao's and Hua's formal portraits hung side by side in rooms and offices in the late 1970s, often with Hua identified by name so people would know who he was. Enormous numbers of posters were published to "push" Hua. At the same time, a number of posters clearly showed who actually held political power. This is obvious from the numerous posters that showed Hua with Ye Jianying closely behind him (as on the 1977 poster 'Laying the foundation').

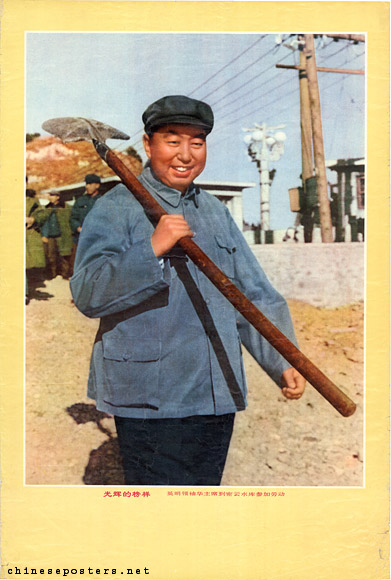

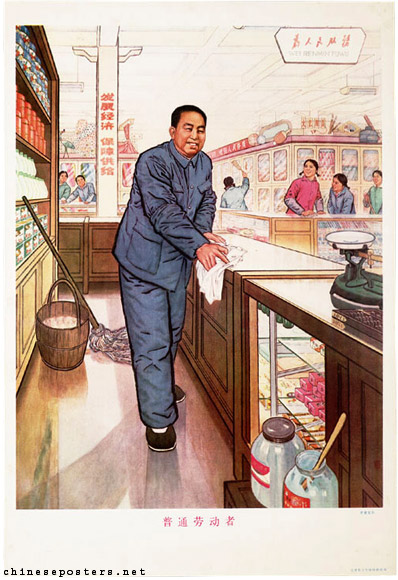

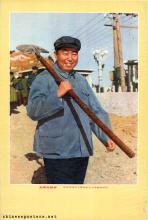

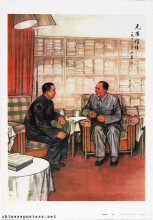

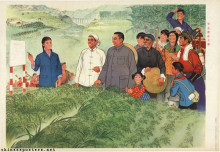

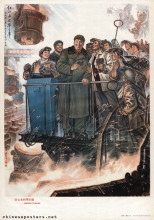

Under Hua's leadership, posters were made that showed him in identical situations as where the Great Helmsman had demonstrated his support. For example, where Mao had put in hard labor at the Ming Tombs in the late 1950s, Hua was shown to do likewise at the Miyun Reservoir in the late 1970s; where Mao was depicted on visits to Dazhai, accompanied by Chen Yonggui and others, Hua was seen to do the same.

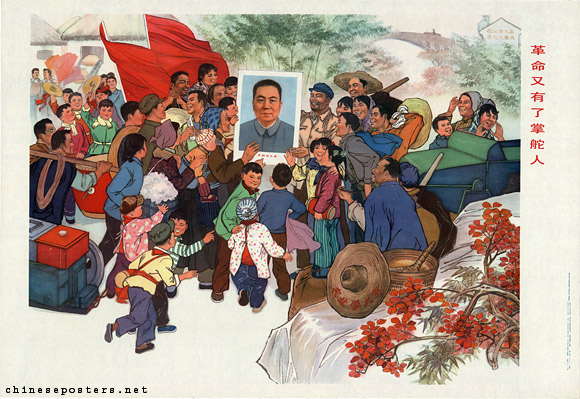

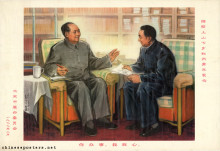

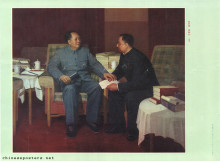

The revolution still has a helmsman, 1977

Hua understandably needed the artistic idiom that previously been centred around Mao to bolster his own claims to power, and in some cases he succeeded in stealing some of the limelight formerly reserved for his predecessor. In other cases, Hua took over the spot in works of art that had until then been reserved for Mao. This seems quite obvious in the 1977 poster 'The revolution still has a helmsman'.

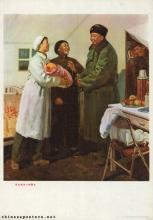

Despite the indications that Mao's policies would continue, Hua's term of office did witness the beginnings of a massive rehabilitation of all those artists and intellectuals who had been prosecuted during the 'ten years of chaos' and even earlier. Many of the artists who had continued painting in the idiom called for by the times, however, found it difficult to shake off the style they had been forced to work in during the Cultural Revolution. Several of them "... complained that their eyes were ruined by the red-hued palette they used throughout the decade".

Dissatisfaction with Hua's political pseudo-alternatives grew rapidly; his ability and wisdom were lambasted as mediocre. By the early 1980s he had lost most of his positions to Deng Xiaoping and the latter's supporters; Hu Yaobang replaced him as Party secretary, Zhao Ziyang took over as Premier, while Deng himself headed the CCP Military Commission. Many 'ordinary' Chinese subscribe to the view that the PLA again was instrumental in this development and even today, they do not hesitate to spontaneously lament Hua's unfair treatment - or "betrayal", as some put it more forcefully - by the PLA elders. Hua retained his membership of the Central Committee. Until his death in August 2008, he led a retired life in Beijing. His calligraphy is greatly admired by connoisseurs.

Dachang Cong, When Heroes Pass Away - The Invention of a Chinese Communist Pantheon (Lanham: University Press of America, 1997)

Ding Wang, Chairman Hua - Leader of the Chinese Communists (London: C. Hurst & Company, 1980)

John Gardner, Chinese Politics and the Succession to Mao (London: The Macmillan Press Ltd, 1982)

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao - The Memoirs of Mao's Personal Physician (London: Random House, 1996)

Hao Li-Ogawa, "Hua Guofeng and China’s transformation in the early years of the post-Mao era", Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies (2022), 1-19

Helmut Martin, Cult & Canon - The Origins and Development of State Maoism (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 1982)

Rudolf G. Wagner, "Reading the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Peking: The Tribulations of the Implied Pilgrim", Susan Naquin & Chün-fang Yü (eds), Pilgrims and Sacred Sites in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992)

Yan Jiaqi & Gao Gao (translated & edited by D.W.Y. Kwok), Turbulent Decade - A History of the Cultural Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1996)

华国锋纪念网 (www.chairmanhua.org)