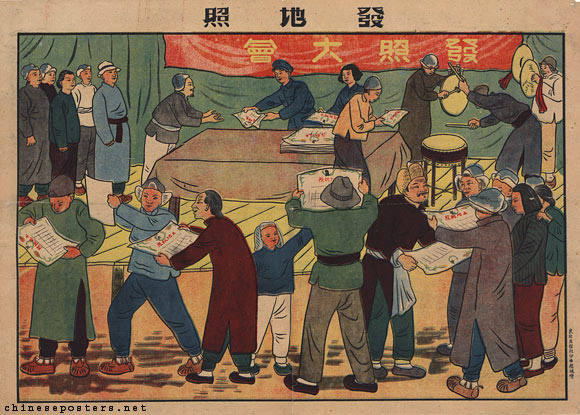

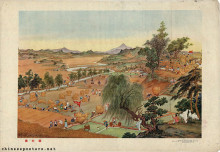

Long before the Land Reform Law was promulgated on 30 June 1950, the CCP had been experimenting with measures to return the land to the vast numbers of peasants. These experiments, which had taken place wherever the party had been able to maintain a stronghold, including the Jiangxi Soviet and Yan'an, had known various radical aspects, but boiled down to the abolishment of landownership by the landlord class and the introduction of peasant landownership. As a result, many peasant households held the deed for their piece of land for the first time ever. A new element that was introduced in 1950 was the provision that the development of agricultural production resulting from this would pave the way for the industrialization of China.

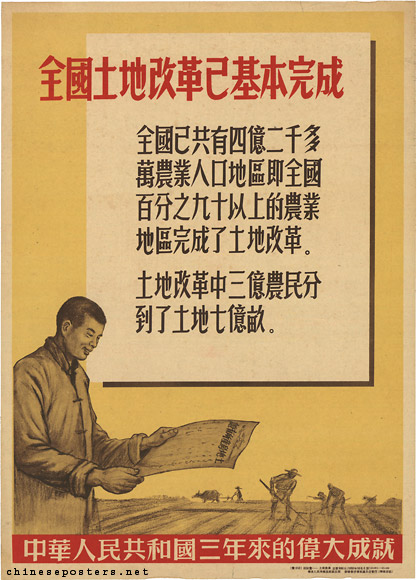

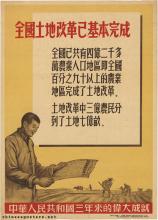

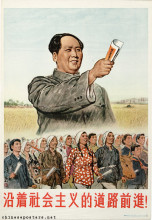

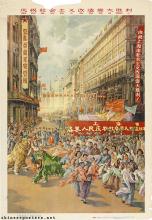

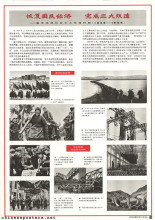

Nationwide agicultural reforms took place from 1950 until the spring of 1953. In some places, the law was executed with more force than was called for, leading to the mistreatment of former landlords. In all, about one million of them were executed. Although the poster above, published in 1952, boasts that land reform basically had been completed, this was only accomplished in 1953. In all, 700 million mu of land (1 mu is .0667 hectares) and various means of production were redistributed among 300 million peasants who had been landless before. Only the areas inhabited by the minority nationalities had not been touched by the Law yet.

Despite the centrality of Land Reform in the party's policies, publication data from 1949 indicate that less than two percent of the total poster production was devoted to typical rural topics, including methods to improve production. This suggests even more strongly the extent to which posters were intended to support other types of mobilizational techniques. It may also point to important shifts that emerged in the political agenda. Shortly after the fields had been turned over to the tiller, preparations began to familiarize the peasantry with the next step in agricultural reform.

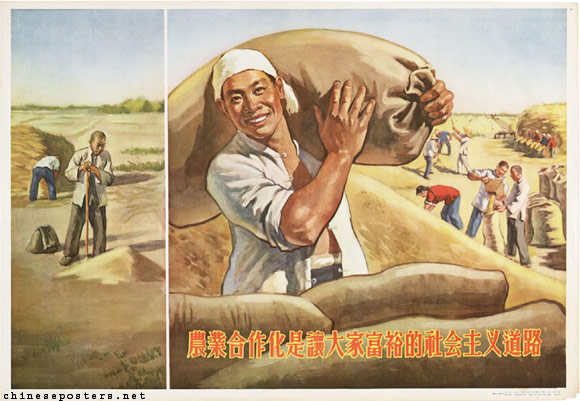

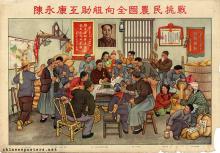

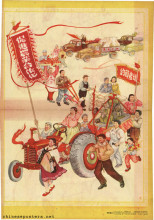

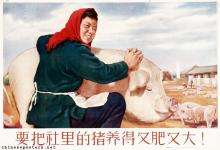

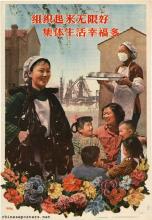

Joining the mutual aid teams is walking the road to common prosperity, 1954

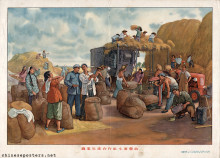

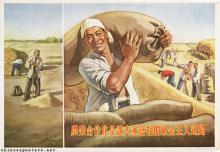

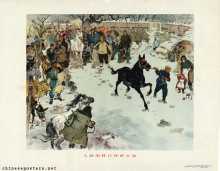

Goods have been delivered in the cooperative, 1954

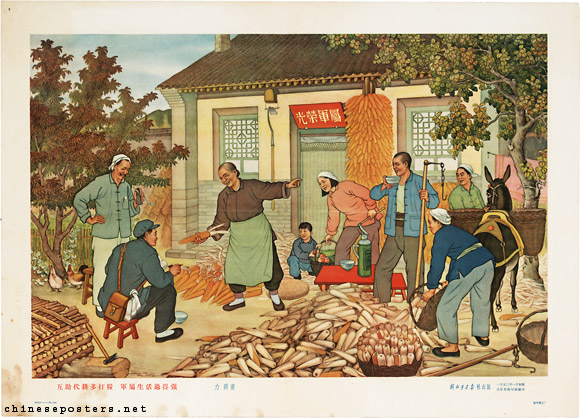

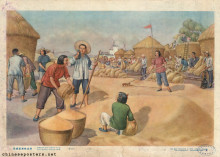

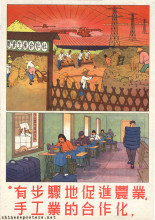

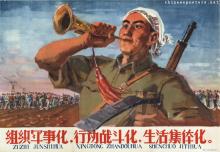

Before long, the land that had been handed out to the peasants was slowly returned to the state. In a process of collectivization that started in 1953, the farmers were first organized in so-called mutual help teams. These were gradually merged into lower agrarian cooperatives. During the Great Leap Forward, these lower forms of cooperatives would be merged into huge People's Communes.

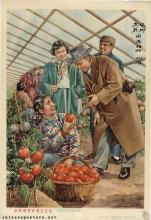

Agricultural cooperativization is the socialist course that makes everybody prosperous, 1956

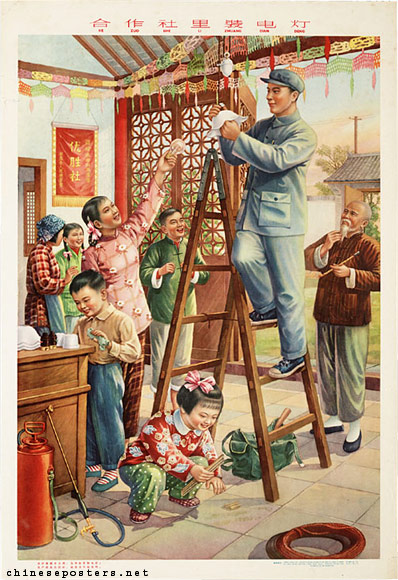

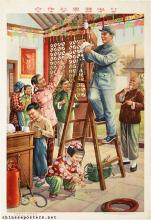

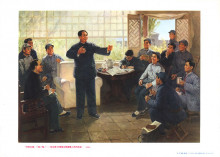

As a result of the collectivization of the countryside, certain amenities and services that had until then been reserved for city dwellers, now came within reach of the rural population. The "electrification of the countryside", in combination with the mechanization of agriculture, was among these. Judging by the poster below, the availability of these amenities was apparently used to entice the people to join such collectives.

Shuo Chen & Xiaohuan Lan, "There Will Be Killing: Collectivization and Death of Draft Animals", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9:4 (2017), 58–77

Jian An, "Yijiuwuling nian nianhua gongzuode jixiang tongji" [Some statistics on New Year print production in 1950], Renmin meishu (2) (April 1950) [in Chinese]

E. Stuart Kirby (ed.), Contemporary China 1955 (London: Oxford University Press, 1956)

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press 1995)

Peter J. Seybolt, Throwing the Emperor from His Horse - Portrait of a Village Leader in China, 1923-1995 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996)