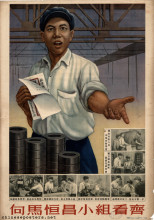

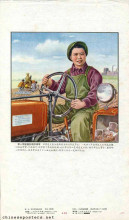

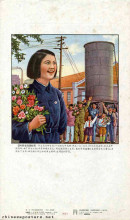

Zhao Guilan at the conference of outstanding workers, 1952

The use of models figured prominently in the political thought of Mao Zedong. He was convinced that everybody constantly had to be made aware of what was correct behaviour, and what conduct was deemed unacceptable; correct ideas would automatically follow from proper behaviour. This was not something Mao had invented. It was based on ideas that had been developed over the centuries by Chinese (political) philosophers: that people could be formed and transformed as if they were clay puppets.

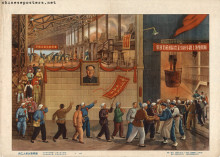

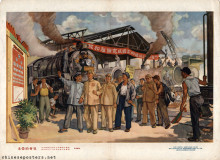

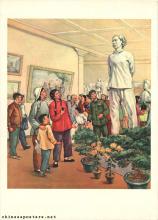

Chairman Mao meets with Model Workers, 1964

According to Mao, when an ordinary person is confronted with a model of ideal behaviour, he will feel a desire to remake himself. This results in a contradiction between the existing values of that person and the new ones he compares himself with. The struggle between these two leads to a new equilibrium, in which the new values are internalized. But the process does not stop there: When confronted with a new model, the equilibrium gives way to a new contradiction. In this way, an eternal cycle of confrontation, internalization and renewed confrontation is created, leading to ever-higher levels of human perfection. Propaganda posters were just one way of presenting models to the masses.

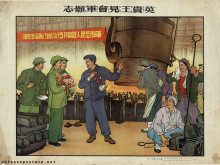

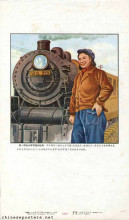

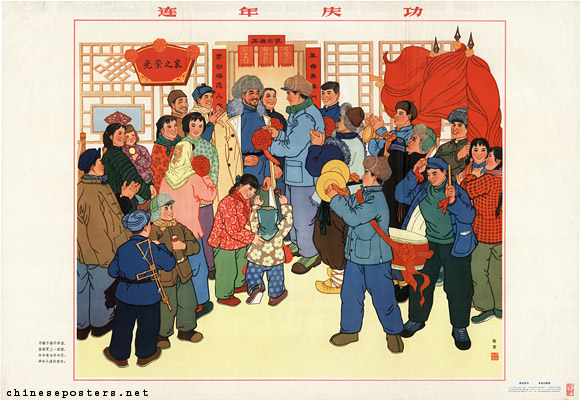

Victories year after year, 1965

Various people of flesh and blood have had the good fortune to become a model; many examples sacrificed themselves for the revolution, like Liu Hulan. Other models merely embodied the "spirit of a screw" by blindly and obediently following superiors. In the 1950s, Party functionaries were held up for study, because they demonstrated boundless love for the people, sacrificed everything they had for the ideals of the party, and were loyal and obedient to boot. Jiao Yulu is a typical example of such a model cadre. Other models included soldiers who had died a martyr’s death in the struggle for power that in the end led to the foundation of the PRC (Dong Cunrui) or who had fallen on the battlefield in Korea.

In the 1960s, the number of soldier-models increased. Among them were Ouyang Hai and Wang Jie, but the best known of them all was Lei Feng. But models could also be non-human. Various production brigades, production processes, break-throughs, historical events, etc. have been seen as models worthy of emulation through the decades.

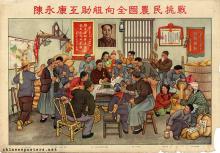

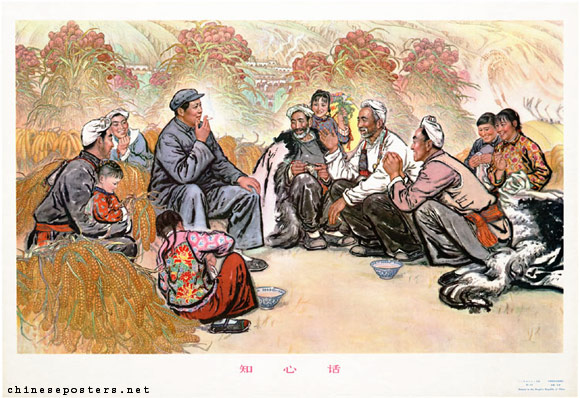

Heart-to-heart talk, early 1970s

Content-wise, the figure of Mao Zedong, as the Great Teacher, the Great Leader, the Great Helmsman, the Supreme Commander, his revolutionary role and his Thought, dominated propaganda in the first half of the Cultural Revolution. Mao, of course, already had appeared prominently on posters dating back as far as the 1940s, despite his warnings against a personality cult. The intensity of his portrayal in the second half of the 1960s, however, was unparalleled. Mao simply was everywhere; his official portrait even hung in every home, often occupying the central place on the family altar.

Mao, then, seemed to be the only permissible subject of the era, the only model displaying behaviour that could be emulated. His image was considered more important than the occasion for which the propaganda poster was designed: in a number of cases, identical posters were published in different years bearing different slogans, in other words, serving different propaganda causes.

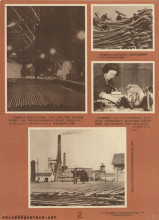

Industry learns from Daqing-Agriculture learns from Dazhai, 1974

Already in the early 1970s, proxies such as Lei Feng and Chen Yonggui (Party Secretary of Dazhai Commune, Shanxi Province; later Vice-Premier) replaced Mao. Other posters were devoted to the ‘new things’ that were seen as the victories of the Cultural Revolution. They featured heroic images of workers, peasants and soldiers waving the Little Red Book and cheering on whatever mass movement was taking place at that moment. Or they highlighted the successes of mass mobilization and self-reliance (by showing the Red Flag Canal), in industry (by showing the industrial model of the Daqing Oilfield) and agriculture (by showing the agricultural model commune of Dazhai), and other models of production. At some point, having one’s own model reflected the power and influence of any leader. Even Jiang Qing succeeded in selecting her own model for emulation in 1974: the village of Xiaojinzhuang, near Tianjin.

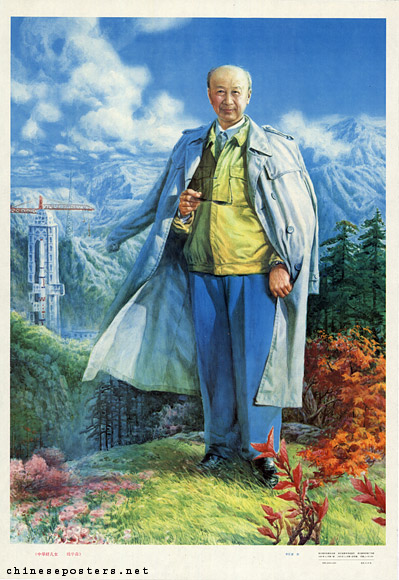

Things changed with Deng Xiaoping’s ascendancy to power in 1977. China embarked on a course of economic modernization and reform. Logically, a new type of model was needed for emulation. These models no longer had to sacrifice themselves for the success of the ‘Four Modernizations,’ but they were held up for the concrete contributions they made to this process. In order to portray such subjects convincingly, models were employed who were relatively prominent in some aspect, but not as perfect and free from shortcomings and errors as before.

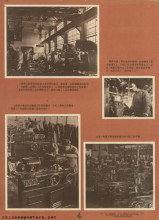

Register of Heroes of the Four Modernizations, 1984

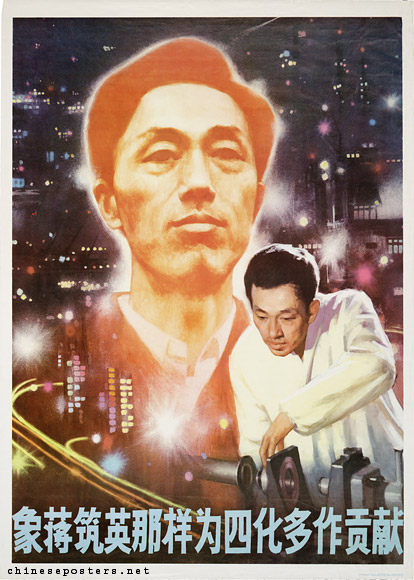

Make many contributions to the Four Modernizations in the same manner as Jiang Zhuying, 1983

The new heroes, reflecting the trend toward diversity and pluralism that became the undercurrent in the China of the 1980s, strove to improve their country and its international position. They valued learning and they contributed to the urgent task of building a socialist spiritual civilization. Perhaps most significantly, they did not necessarily belong to the former pillars of society (workers, peasants or soldiers), but could also be intellectuals or students. Invariably, they are the ones wearing lab coats and glasses. But it lasted all the way to 2003 before the leadership finally indicated that martyrdom was not a necessary prerequisite to become a hero.

In propaganda aimed at intellectuals, elderly, male intellectuals played a major role. The optics specialist Jiang Zhuying, who died in 1982, served as an important intellectual model in the early 1980s. Later, the father of the Chinese space program, Qian Xuesen, became the most well-known intellectual appearing in propaganda posters. In an ironic twist of fate, the Shanghai plumber Xu Hu, who repairs toilets in his spare time, became a national model in the late 1990s.

Jeremy Brown, "Staging Xiaojinzhuang: The City in the Countryside, 1974-1976", in Joseph W. Esherick, Paul G. Pickowicz, Andrew Walder (eds), The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006)

Chiang Chen-ch’ang, "The New Lei Fengs of the 1980s", Issues and Studies (March 1984), 22-42

He Xiaozhong, "Survey Report on Idol Worship Among Children and Young People", Chinese Education and Society 39:1 (2006), 84–103

Chang-tai Hung, "The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China", Journal of Contemporary History 43:2 (2008), 279–304

Donald J. Munro, The Concept of Man in Contemporary China (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1977)

Lucian W. Pye, The Mandarin and the Cadre: China’s Political Cultures (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies/University of Michigan, 1988)

Peter J. Seybolt, Throwing the Emperor from His Horse - Portrait of a Village Leader in China, 1923-1995 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996)

Shao Wu et al. (eds), 共和国群英谱 [Gongheguo qunyingpu - Register of heroes of the Republic] (Beijing: Zhongguo shaonian ertong chubanshe, 2003) [in Chinese]

James L. Watson, "The Renegotiation of Chinese Cultural Identity in the Post-Mao Era,", in Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom and Elizabeth J. Perry (eds), Popular Protest and Political Culture in Modern China: Learning from 1989 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992)

Xu Yan, 80 wei gongchandang rende gushi [The stories of 80 Communist Party personages] (Beijing: Jiefangjun wenyi chubanshe, 2001) [in Chinese]

Elya J. Zhang, "To Be Somebody: Li Qinglin, Run-of-the-Mill Cultural Revolution Showstopper", in Joseph W. Esherick, Paul G. Pickowicz, Andrew Walder (eds), The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006)

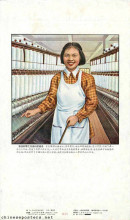

![[Model workers]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/d91-103.jpg?itok=opm33aH8)