The author of this text is Dong Zhengyi (董正谊, 1917-1989; in this publication the transcription 'Tung Cheng-yi' is used). He was one of the best known peasant painters from Huxian. His most famous picture was The commune's fishpond.

This text was published in Peasant paintings from Huhsien County of the People's Republic of China (Los Angeles : US-China Peoples Friendship Association, 1977).

I grew up before Liberation. In the old society no one taught me to paint, nor did I have any political ideas. I just painted in my spare time, copying things. At primary school I was forced to learn the three-character classics of Confucius. In this book were some illustrations and I liked the book because I could copy from them and draw in their style. But our family was very poor and I had only one brush, which had to last for several years and which I used for writing as well.

Because my family had suffered so much I was filled with discontent at society. I was often infuriated at the sight of poor people being beaten. Owing to the fact that I was personally oppressed I expressed my feelings by drawing like the poets, hermits, and recluses who retreated from society.

When Liberation came I was given some land and some animals. During the land reform I was made leader of the land distribution group. I was very delighted with Liberation because the land was returned to me and I was filled with affection for the Party and for Chairman Mao and I realized that China had at last returned to the hands of the Chinese people.

I was very happy and content to engage in agriculture until I953 when the county Party Committee organized a short course to create a “Fine Arts Backbone Force." During the course I studied Chairman Mao's Talks at the Yenan Forum. It was also the time the Party called on us to transform nature. With every revolutionary movement I would engage in creative work that was closely connected with the movement's aim.

We artists paint the future and also the revolutionary ideal, not just things as they are. In our village the fishpond is not exactly like this ; there's a wall round it. But in order to reflect the bright future I took out the wall. To express the bumper harvest, all the fish are jumping, all their scales are bright and shining. The little fish are escaping from the net. The net lets them through. The little fish are the new generation growing up. This is intended to show development; we don't eat up all the fish.

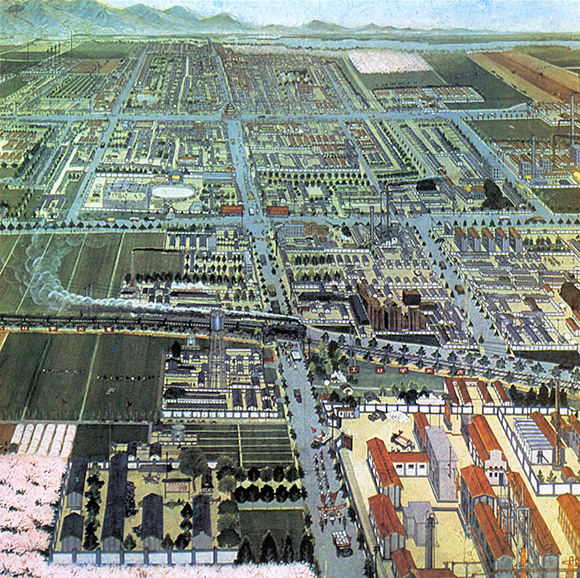

My painting New Look of Huhsien was chosen to go on exhibition at the Afro-Asian writers' conference. The painting, done in 1953, was a contrast and repudiation of the old society compared with the new. Compared with the terrible state of the old town, which was often ransacked by warlords and impoverished by the landlord families until it looked like nowhere on earth, the town now was relatively rich, with communes and factories, and the situation was excellent. The people who lived at the foot of the mountain used to live only in thatched huts. By I970 the people there had very spacious houses with two rooms, three rooms, and even six rooms. The peasants there used to be oppressed by four landlord families and had only ragged clothes of coarse cloth. Now they have better clothes than the landlords had. All the houses have tiled roofs. With the development of agriculture the brigade has forestry and fisheries projects.

From that time on all my pictures have been painted on the basis of the three great revolutionary movements - the class struggle, the struggle for production, and scientific experiment. In I958 all the people in our country were mobilized to make more iron and steel. I painted how the people were smelting iron and steel.

Thousands and thousands of people were changing the mountains and rivers - I painted that too. By the end of I973 I had painted over two hundred pictures.