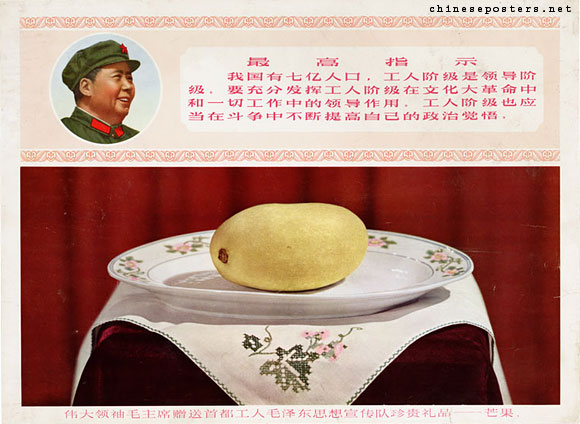

In August 1968, Mao Zedong received a delegation from Pakistan, headed by the foreign minister. At that occasion, he was presented with a basket of mangoes. According to some stories, Mao actually disliked mangoes, but the fruits were given an important and symbolic role in the complex political situation of the Cultural Revolution. For Mao did not eat the mangoes himself, but presented all seven of them to a corresponding number of Worker-Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Teams that were active in the capital. These Teams had been sent to universities and factories to restore order and bring an end to the intense and bloody factional struggles between various groups of Red Guards. The media at the time reported that the gift was intended to mark the second anniversay of Mao’s own big-character-poster Bombard all Headquarters. In reality, the mangoes served to indicate that Mao had become dissatisfied with the Red Guards, and henceforth would support the Teams. The Red Guards subsequently were sent to the countryside to learn from the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants in the Up to the mountains, down to the villages-campaign.

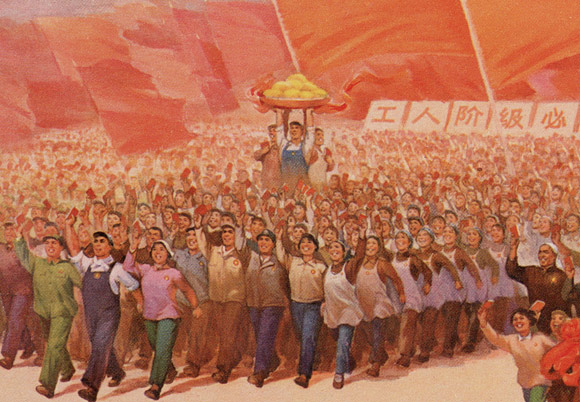

Detail from poster ’Forging ahead courageously while following the great leader Chairman Mao!’, 1969

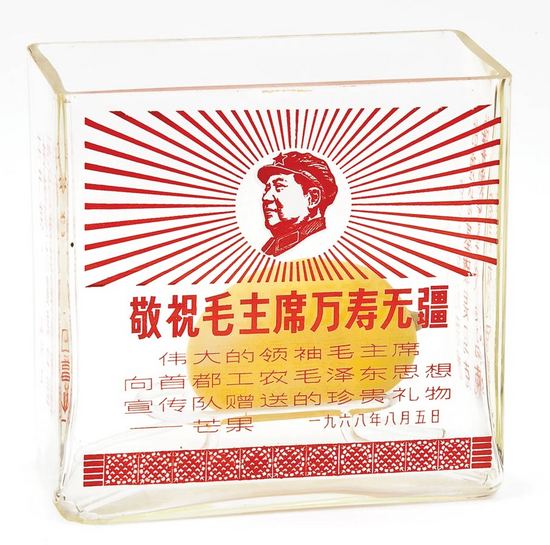

The factories and universities that received the mangoes were overfilled with joy at this Great, Greatest, Happiest of Events. Many became obsessed with the question how to preserve the gift. In one case, the mango was put in a small glass box, engraved with an inscription and an image of Mao with rays of sunshine emanating from his head. The Beijing People’s Printing Agency, on the other hand, decided to place the mango in a jar of formaldehyde, to preserve it for all eternity (according to later reports, this particular mango unfortunately turned black and shriveled). In still another case, the mango was put in a huge tank of water; all employees of the factory were given a small amount of that water to drink and to be literally filled with the spirit of Mao. Although the media had a field day, although pages were filled with mango mania and even posters were published, there is no mention anywhere of someone actually eating one of the fruits. After all, nobody would have been worthy of this privilege but Mao himself. But the fact of the gift itself was celebrated and commemorated.

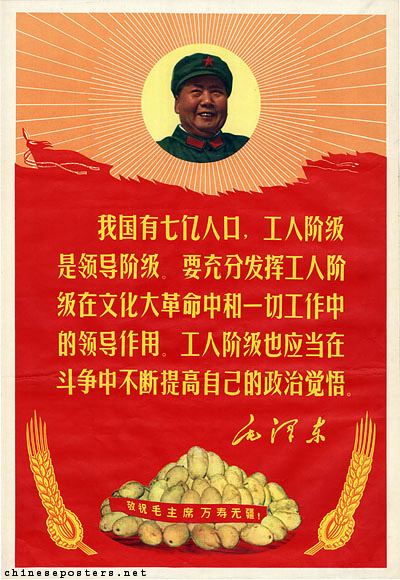

Our country has 700 million people ..., ca. 1969

Mangoes feature on buttons and posters of the period, as ornament or carried on dishes. Mango reliquaries with wax or plastic mangoes were mass produced. These can now be found for sale on antique markets and on websites - although most probably do not date from around 1968.

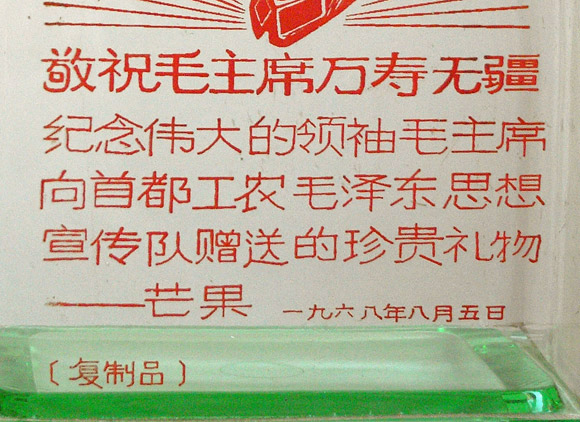

Mango reliquary, believed to date from around 1970, from the auction catalog ‘Mao and the Arts of New China’, Bloomsbury Auctions, London, 5 November 2009 ![]() . The inscription reads ‘Respect and Wishes to Chairman Mao for a Long Life, Commemorate Great Leader Chairman Mao who gave this cherished gift - Mango - to Capital Workers Peasant Mao Tse-tung Thought Propaganda Team’.

. The inscription reads ‘Respect and Wishes to Chairman Mao for a Long Life, Commemorate Great Leader Chairman Mao who gave this cherished gift - Mango - to Capital Workers Peasant Mao Tse-tung Thought Propaganda Team’.

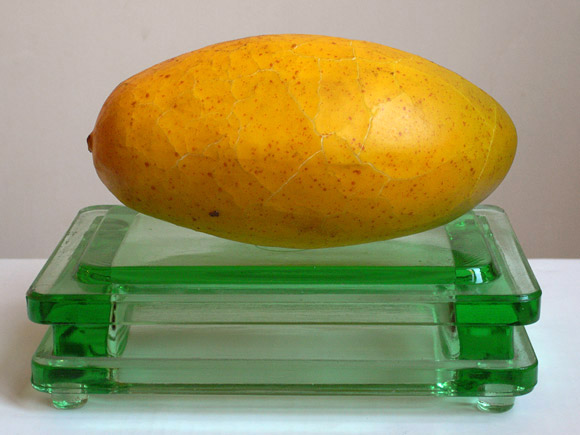

Mango reliquary from the Landsberger collection.

The text is similar to the contemporary reliquary shown above, but states (between brackets) that this is a modern replica.

The mango.

Robert Benewick, "Icons of Power: Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution", in Harriet Evans and Stephanie Donald (eds), Picturing Power in the People’s Republic of China - Posters of the Cultural Revolution (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1999), 123-137

Adam Yuet Chau, "Mao’s Travelling Mangoes: Food as Relic in Revolutionary China", Past and Present (2010), Supplement 5, 256-275

Alice de Jong, "The Strange Story of Chairman Mao’s Wonderful Gift", Reminiscences and Ruminations - China Information Anniversary Supplement 9:1 (1994), 48-54

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao - The Memoirs of Mao’s Personal Physician (London: Random House, 1996)

Alfreda Murck, "Golden Mangoes - The Life Cycle of a Cultural Revolution Symbol", Archives of Asian Art, vol. 57 (2007), 1-21

Alfreda Murck, Mao’s Golden Mangoes and the Cultural Revolution (Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2013)

Melissa Schrift, Biography of a Chairman Mao Badge - The Creation and Mass Consumption of a Personality Cult (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2001)