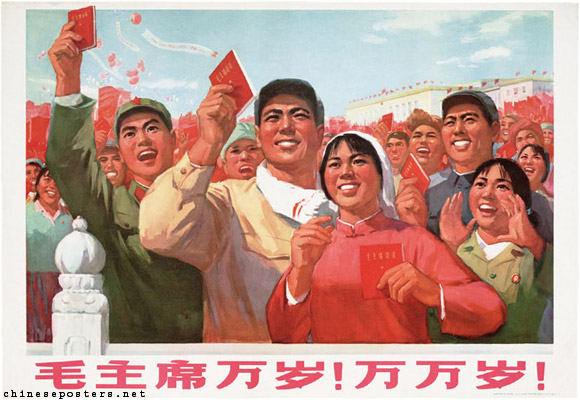

Comrade Mao Zedong is the greatest Marxist-Leninist of the present age, 1969

In 1962, Mao advocated the Socialist Education Movement (SEM), in an attempt to 'inoculate' the peasantry against the temptations of feudalism and the sprouts of capitalism that he saw re-emerging in the countryside. Large doses of didactic politicized art, whether figurative or literary, were produced as serum for this inoculation process. The Party organization saw the initiatives proposed by Mao and his even more radical followers as interfering with its successful program of economic rehabilitation that had started after the Great Leap Forward.

Given the scope of the problems, the Party preferred more technocratic solutions and was averse to Mao's millennial visions. There are no indications that open opposition to Mao actually existed, although the Chairman believed there was. He was truly convinced that the more moderate leaders were trying to steal his place in history by subverting the nature of the revolution he had fought for. In order to reclaim his rightful place at the apex of power and to oust those he perceived as revisionists, Mao turned towards the People's Liberation Army, the only organization he still deemed ideologically correct.

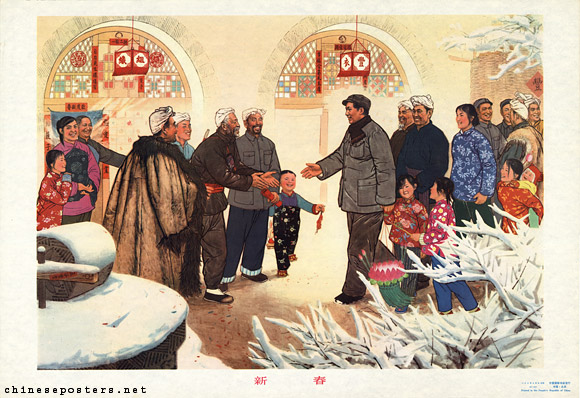

Chairman Mao gives us a happy life, 1954

Mao already had appeared prominently on propaganda posters as far back as the 1940s, despite his ambiguous warnings against a personality cult. The intensity of his portrayal in the second half of the 1960s, however, was unparalleled. Under Lin Biao, the PLA increasingly was employed to bolster the personality cult around Mao, and thus to produce art that would contribute to the construction of Mao's god-like image. All this took place with Mao's consent. Already before the compilation of the Quotations from Chairman Mao (Mao zhuxi yulu 毛主席语录, the 'Little Red Book', published in May 1964) for use by the armed forces, the PLA had been turned into "a great school of Mao Zedong Thought". The army became the driving force behind the campaign to study Mao's Quotations.

A study session with the Quotations "... supplied the breath of life to soldiers gasping in the thin air of the Tibetan plateau; enabled workers to raise the sinking city of Shanghai three-quarters of an inch; inspired a million people to subdue a tidal wave in 1969, inaccurate meteorologists to forecast weather correctly, a group of housewives to re-invent shoe polish, surgeons to sew back severed fingers and remove a ninety-nine pound tumor as big as a football."

Warriors love reading Chairman Mao's books most, 1966

The PLA also supplied most of the behavioural models that embodied the "spirit of a screw" (luosiding jingshen 螺丝钉精神) by blindly following the instructions from the Party and/or superiors and attachment to the larger group. The best known of these were model soldiers as Lei Feng, Wang Jie, Dong Cunrui, and Ouyang Hai.

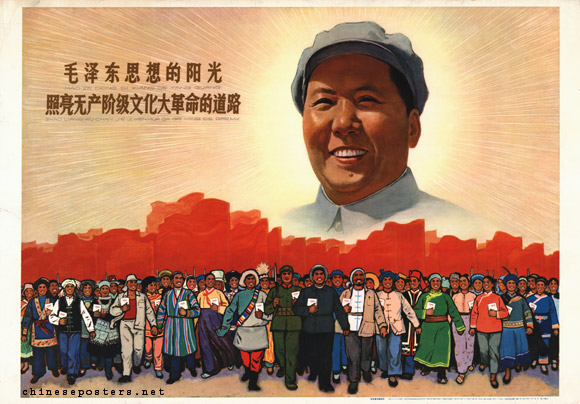

Logically, the Army became responsible for art. This art should unite and educate the people, inspire the struggle of revolutionary people and eliminate the bourgeoisie. Art had to be guided by Mao Zedong Thought, its contents had to be militant and to reflect real life. Proletarian ideology, communist morale and spirit, revolutionary heroism were the messages of a new type of hyper-realism that took precedence over style and technique and that differed in all aspects from art creation until then. In the PLA paintings of the time, the color red featured heavily; it symbolized everything revolutionary, everything good and moral; the color black, on the other hand, signified precisely the opposite. Color symbolism continued to be important in the following years, not only in visual propaganda, but in printed propaganda as well.

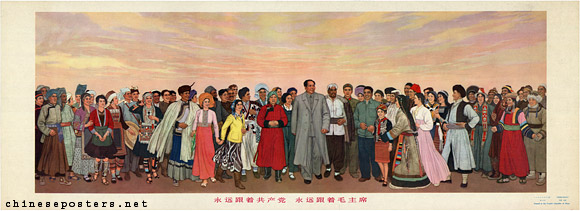

Follow the Communist Party for ever, follow Chairman Mao forever, early 1970s

Mao's wife Jiang Qing supported the artistic direction set by the PLA. The conceptual dogmas and theatrical conventions provided by the model operas (yangbanxi 样板戏) that she supported also became the standard in the visual arts. For the stage, she formulated the 'three prominences' (三突出, stress positive characters; stress the heroic in them; stress the central character of the main characters). In the arts, this was translated as: the subjects were to be portrayed realistically, and they were always to be in the centre of the action, flooded with light from the sun or from hidden sources. Moreover, when we look at the propaganda posters of these years, it always seems as if we, the spectators, are looking upward, as if the action is indeed taking place upon a stage.

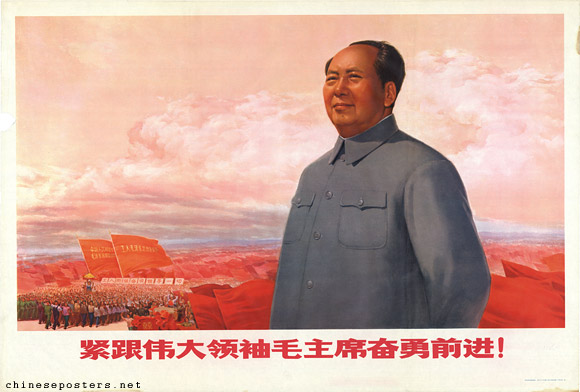

The subjects were represented hyper-realistically, as ageless, larger-than-life peasants, soldiers, workers and educated youth in dynamic poses. Their strong and healthy bodies functioned as metaphors for the strong and healthy productive classes the State wanted to propagate. In line with the egalitarian character of the Maoist culture of the body, the gender distinctions of the subjects were by and large erased - something that was also attempted in real life. Men and women alike had stereotypical, "masculinized" bodies; they were dressed in cadre grey, army green or worker/peasant blue; their hands and feet often were absurdly big in relation to the rest of their bodies; and their faces, including short-cropped hairdos and chopped-off pigtails, were done according to a limited standard repertoire of acceptable examples. Even in the many propaganda posters that featured Mao, the Chairman was subjected to these stylistic dictates. As a result, he appeared as a muscular super-person.

As the Great Teacher, the Great Leader, the Great Helmsman, the Supreme Commander, Mao came to dominate the propaganda art of the first half of the Cultural Revolution. His image was considered more important than the occasion for which a particular work of propaganda art was designed: in a number of cases, identical posters dedicated to Mao were published in different years bearing different slogans, i.e., serving different propaganda causes.

Reporting to Chairman Mao, 1974

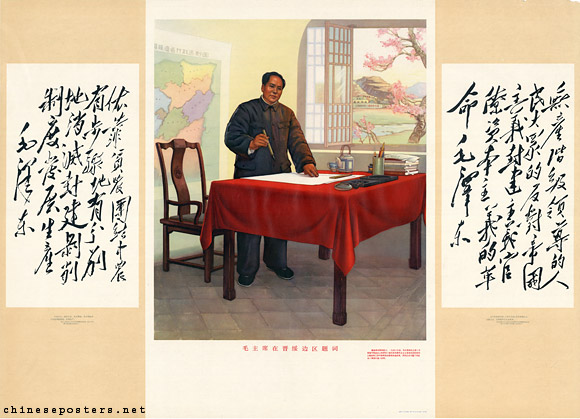

Mao could be depicted as a benevolent father, bringing the Confucian mechanisms of popular obedience into play. Or he was portrayed as a wise statesman, an astute military leader or a great teacher; to this end, artists represented him in the vein of the statues of Lenin, which had started to appear in the early 1920s in the Soviet Union. Another group of posters visually recounted the more illustrious of his historical deeds.

Chairman Mao writes an inscription in the Jinsui Border Area, 1972

The working class must exercise leadership in everything, 1970

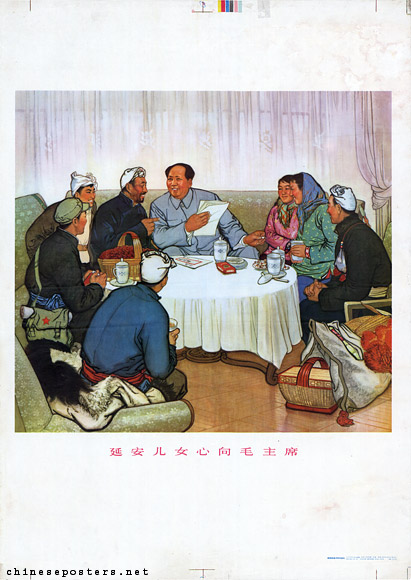

But no matter how Mao was depicted, he had to be painted hong, guang, liang (红光亮, red, bright, and shining); no grey was allowed for shading, and the use of black was interpreted as an indication that the artist harbored counter-revolutionary intentions. His face was painted usually in reddish and other warm tones, and in such a way that it appeared smooth and seemed to radiate as the primary source of light in a composition. In many instances, Mao's head seemed to be surrounded by a halo which emanated a divine light, illuminating the faces of the people standing in his presence.

The hearts of the sons and daughters of Yan'an go out to Chairman Mao, 1974

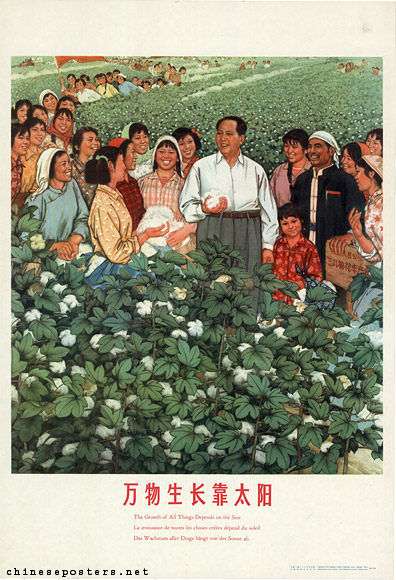

As a super model, every detail of his representations had to be preconceived along ideological lines and invested with symbolic meaning. An extreme example of this is the painting-turned poster Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan. As a consequence of these creative rules governing the depiction of Mao, the more god-like and divorced from the masses he became to be portrayed, often hovering above those masses. And yet, despite this apparent distance, there was something in the Mao images that struck a chord with the people, something recognizable that turned him into an EveryMao. Mao somehow remained united with the people, whether he inspected fields, shook hands with the peasants, sat down with them, and shared a cigarette with them; whether he inspected factories or infra-structural works, joked with the workers, and possibly shared a cigarette with them; whether he was dressed in military uniform, discussing strategy with military leaders, inspected the rank-and-file, or mingled with contingents of Red Guards; whether he stood on the bow of a ship, dressed in a terry cloth bathrobe after an invigorating swim in the Yangzi River; whether he headed a column of representatives of the national minorities; or received a delegation of foreign visitors.

As the Cultural Revolution unfolded, Mao became a regular presence in every home, either in the form of his official portrait, or as a bust or other type of statue. Not having the Mao portrait on display indicated an apparent unwillingness to go with the revolutionary flow of the moment, or even a counter-revolutionary outlook, and refuted the central role Mao played not only in politics, but in the day-to-day affairs of the people as well. The formal portrait often occupied the central place on the family altar, or at least the spot where that altar had been located before it had been demolished by Red Guards in the early days of the Cultural Revolution. This added to the already god-like stature of Mao as it was created in propaganda posters.

Respectfully wish Chairman Mao eternal life!, 1968

The days were structured around the ritual of "asking for instructions in the morning, thanking Mao for his kindness at noon, and reporting back at night". This involved bowing three times, the singing of the national anthem, reading passages from the Little Red Book in front of Mao's picture or bust, and would end with wishing him 'Ten thousand years'. In the mornings, everybody would announce what efforts they would make that day for the revolution. In the evenings, people would report on their accomplishments or failures and announce their resolutions for the next day. The rituals were often accompanied by dancing the 'loyalty dance' (zhongzi wu 忠字舞), which did not involve much more than stretching one's arms from the heart to Mao's portrait. The movements, originating from a folk dance popular in Xinjiang, was accompanied by the song "Beloved Chairman Mao".

Forging ahead courageously while following the great leader Chairman Mao, 1969

In the early 1970s, the extreme and more religious aspects of Mao's personality cult were being dismantled. In propaganda posters, proxies such as Lei Feng - or one of his reincarnations - and Chen Yonggui (the model Party secretary of Dazhai Commune) often replaced Mao himself. This did not diminish the adulation of Mao, who continued to lead the CCP as it was being rebuilt. The excesses committed by the people during the heyday of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s, including the embarrassing habit of "3,000 years of emperor-worshipping tradition" which Mao himself had consciously promoted and in which he himself had basked, were attributed to Lin Biao, who had - quite literally - fallen from grace in 1971. Similarly, the Army, the former "great school of Mao Zedong Thought", no longer functioned as a model for the people. Instead, the "fine work style" of the CCP and the masses were what the army needed to learn from.

The growth of all things depends on the sun, early 1970s

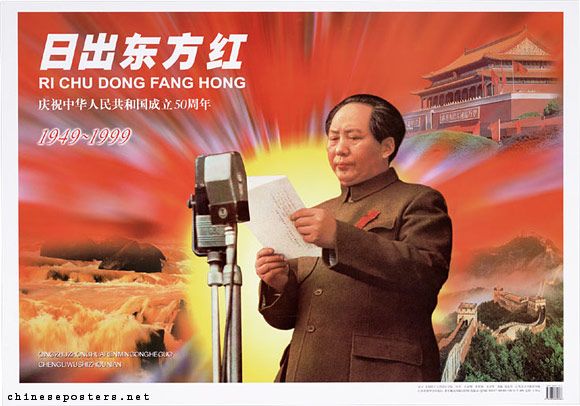

After the Cultural Revolution, the propagation of the divine presence and the accomplishments of the supreme leader would never again be repeated in the same intensity, sophistication, and mind-numbing density. In the China of economic reforms and Open Door policy, the production of posters containing ideological exhortations was replaced more and more in the 1980s by those stressing economic construction, or even ordinary commercial advertisements. In the early 1990s, a resurgence of the popular belief in the protective qualities of a truly god-like Mao did take place. This MaoFever coincided with the marking of the centenary of his birth. The continued importance of Mao as a political symbol is attested to by the issuance of a new 100-yuan bank note in 1999 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the PRC: the image of a youngish Mao graces the bill. He moreover appeared in a special series of posters, also showing Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin (the so-called "three generations of leaders"), to mark the occassion.

More posters on the Mao Cult:

David Apter & Tony Saich, Revolutionary Discourse in Mao's Republic (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1994)

Geremie Barmé, Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe 1996)

Dachang Cong, When Heroes Pass Away - The Invention of a Chinese Communist Pantheon (Lanham MD, etc.: University Press of America, 1997)

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham, etc.: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Stefan Landsberger, "The Deification of Mao: Religious Imagery and Practices during the Cultural Revolution and Beyond", in Woei Lien Chong (ed.), China's Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution: Master Narratives and Post-Mao Counternarratives (Asia/Pacific/Perspectives) (Lanham MD, etc.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2002), pp. 139-184

Daniel Leese, Mao Cult - Rhetoric and Ritual in China's Cultural Revolution (Cambridge, etc.:Cambridge University Press, 2011)

Li Zhensheng, Red-Color News Soldier - A Chinese Photographer's Odyssey through the Cultural Revolution (London, etc.: Phaidon Press, 2003)

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao - The Memoirs of Mao's Personal Physician (London, etc.: Random House, 1996)

Lu Xing, Rethoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution - The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture and Communication (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2004)

Helmut Martin, Cult & Canon - The Origins and Development of State Maoism (Armonk, NY, etc.: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 1982)

Melissa Schrift, Biography of a Chairman Mao Badge - The Creation and Mass Consumption of a Personality Cult (New Brunswick, etc.: Rutgers University Press, 2001)

Frederick C. Teiwes, Politics and Purges in China - Rectification and the Decline of Party Norms, 1950-1965 (Second Edition) (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe 1993)

Frederick Teiwes and Warren Sun, The Tragedy of Lin Biao - Riding the Tiger During the Cultural Revolution 1966-1971 (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press 1996)

Ross Terrill, Madame Mao - The White-Boned Demon (Toronto, etc.: Bantam Books 1984)

Roxane Witke, Comrade Chiang Ch'ing (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1977)

Yan Jiaqi & Gao Gao (translated & edited by D.W.Y. Kwok), Turbulent Decade - A History of the Cultural Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press 1996)

Yang Kelin (ed.), 文化大革命博物馆 [Museum of the Cultural Revolution] (Hong Kong: Dongfang chubanshe youxian gongsi, Tiandi tushu youxian gongsi 1995)

The 110 commemoration of Mao Zedong's birth (December 2003) [in Chinese]