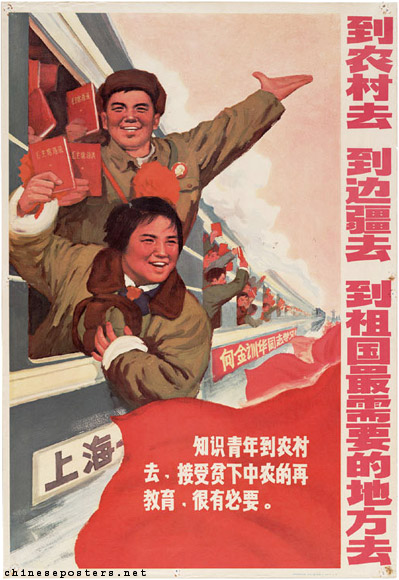

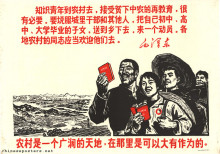

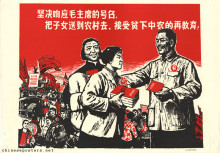

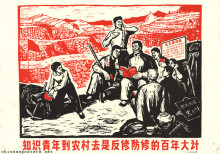

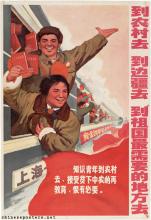

From December 1968 onward, millions of educated urban youth (zhishi qingnian, 知识青年), consisting of secondary school graduates and students, were mobilized and sent "up to the mountains and down to the villages" (上山下乡, shangshan xiaxiang), i.e. to rural villages and to frontier settlements. In these areas, they had to build up and take root, in order to be reeducated by the poor and lower-middle peasants, the lowest classes in China.

This relocation program was practiced first on a limited scale before the Great Leap Forward Movement, resumed in the early 1960s, and accelerated sharply by the late 1960s.

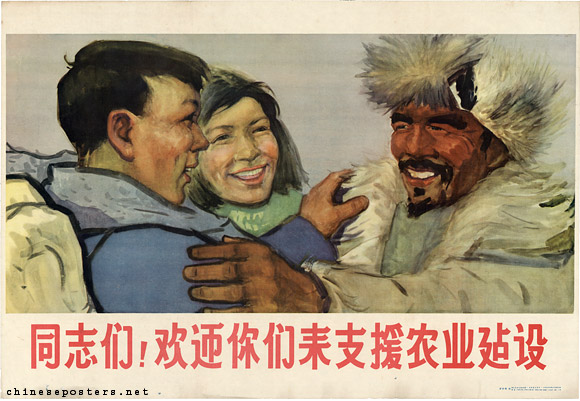

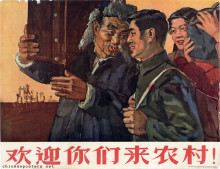

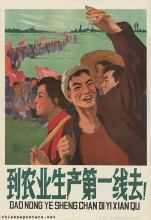

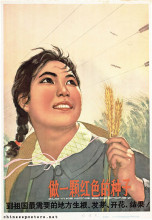

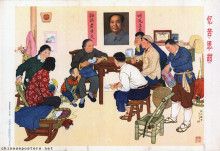

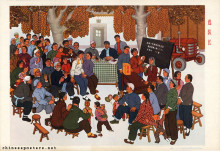

Comrades! You are welcome to support the construction of agriculture, 1958

While some 1.2 million urban youths were sent to the countryside between 1956 and 1966, no less than 12 million were relocated in the period 1968-1975; this amounts to an estimated 10% of the 1970 urban population. In principle, the program called for lifelong resettlement in the rural areas, but toward the end of, and in particular after the Cultural Revolution, many were finally able to find jobs or to be transferred back to the cities. A great number of them, however, had resigned themselves to their fate and decided to remain.

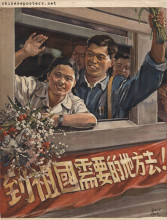

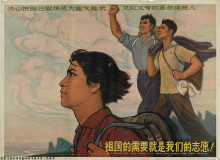

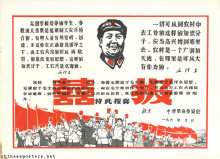

Making a collective report to the mother university, 1965

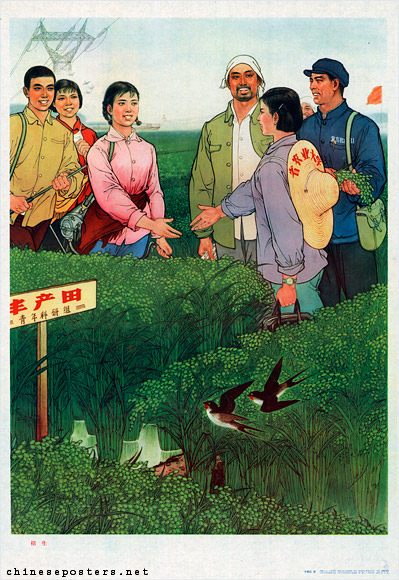

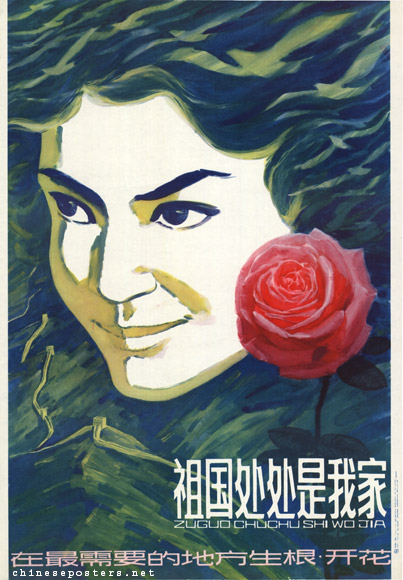

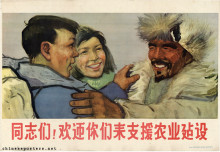

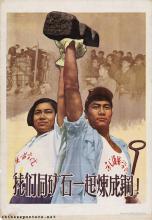

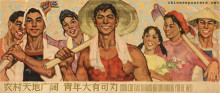

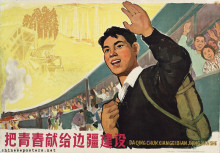

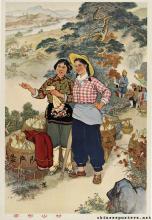

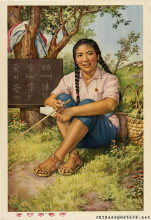

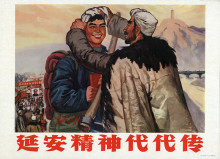

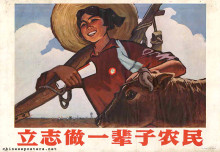

Judging from the many posters that were dedicated to shangshan xiaxiang, showing idyllic rural scenes, the youngsters all enjoyed the wholesome life in the countryside, and thrived under the stern but correct ideological guidance provided by the peasants. All this should transform them into "new-style, cultured peasants". The young intellectuals were also seen as conveyor belts for technology transfer, as bringers of new knowledge to the rural villages.

In reality, and similar to the May Seven cadre school program, however, many peasants living in the areas where urban youths were resettled resented their arrival. They often saw the youngsters from the cities, who in their eyes did not amount to much in terms of labor power, as a threat to their own survival. Many students could not deal with the harsh life and died in the process of reeducation.

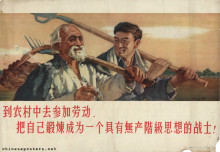

Spring breeze in Yangliu, 1975

The main reason behind the acceleration of the relocation program in 1968 was an attempt to bring the Red Guards under control and to halt the intense factional struggle and civil strife. With the schools still closed, the government did not know what to do with the millions of urban young. One way to solve the problem was to send the students away to the rural areas and let them fend for themselves. Over the years, many of those who were sent away slowly started to realize this. Although the resentment this created found something of an outlet during the "Beijing Spring Movement" of 1978-1980, it contributed to a general decline of support for the Party and apathy for all things political.

Despite the negative experiences of many, the government reintroduced a reallocation program in the 1980s - an elective one, this time. Few people were interested, unless they managed to secure extra allowances or hardship pay. Some rare exceptions aside, most urban youth prefer to remain in the cities.

Thomas P. Bernstein, Up to the Mountains and Down to the Villages: The Transfer of Youth from Urban to Rural China (New Haven: Yale University Press 1977)

Michel Bonnin, Génération perdue. Le mouvement d’envoi des jeunes instruits à la campagne en Chine, 1968-1980 (Paris: Editions de l’EHESS, 2004)

David Davies, "Old Zhiqing Photos: Nostalgia and the 'Spirit' of the Cultural Revolution", The China Review 5:2 (2005), 97-123

David Davies, "Visible Zhiqing: The Visual Culture of Nostalgia Among China's Zhiqing Generation" in Guobin Yang & Ching Kwan Lee (eds.), Re-envisioning the Chinese Revolution (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), 166-192

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Yarong Jiang & David Ashley (eds.), Mao's Children in the New China - Voices from the Red Guard Generation (London: Routledge, 2000)

Anne McLaren, "The Educated Youth Return: The Poster Campaign in Shanghai From November 1978 to March 1979", Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 2 (1979), 1-20

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People's Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press 1995)

Li Zhensheng, Red-Color News Soldier - A Chinese Photographer's Odyssey through the Cultural Revolution (London: Phaidon Press, 2003)

Political Department of the Heilongjiang Production and Construction Corps (ed), Zhishi qingnian zai Beidahuang [Educated youth in the Great Northern Wilderness] (Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe, 1973) [in Chinese]

Michael Schoenhals (ed.), China's Cultural Revolution, 1966-1969 - Not A Dinner Party (Armonk: M.E Sharpe, 1996)

Peter J. Seybolt, Throwing the Emperor from His Horse - Portrait of a Village Leader in China, 1923-1995 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996)

Bin Xu, "Historically Remaining Issues: The Shanghai-Xinjiang Zhiqing Migration Program and the Tangled Legacies of the Mao Era in China, 1980-2017", Modern China (2021), 1-33

Elya J. Zhang, "To Be Somebody: Li Qinglin, Run-of-the-Mill Cultural Revolution Showstopper", in Joseph W. Esherick, Paul G. Pickowicz, Andrew G. Walder (eds), The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006)

Old Pictures from China  , taken by Herbert Chang who was sent to the countryside in 1968. In 1999, he returned and has photographed scenes for comparison.

, taken by Herbert Chang who was sent to the countryside in 1968. In 1999, he returned and has photographed scenes for comparison.