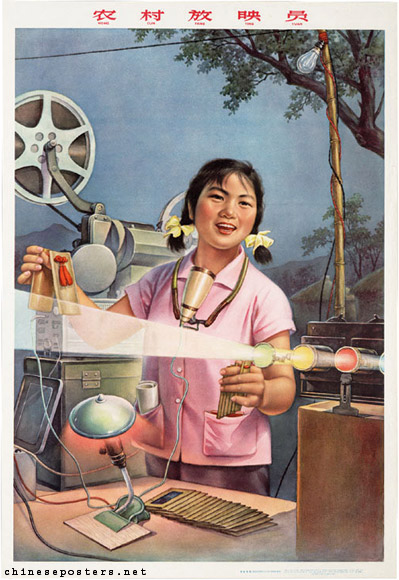

The projectionist of the village, 1966

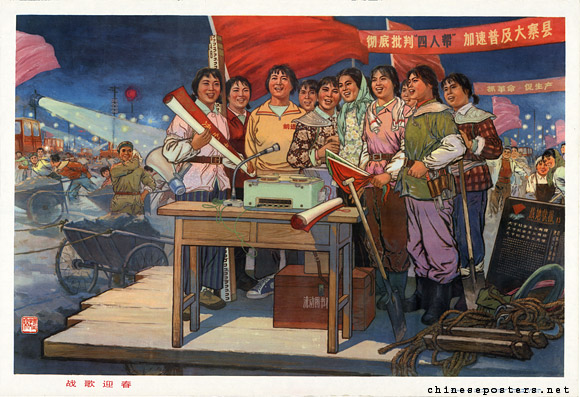

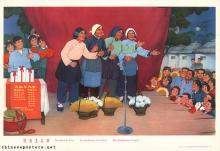

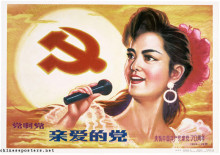

On many occasions, both younger and elder women were shown on posters while praising the accomplishments of socialism. Within the framework of what was considered appropriate during the high tide of Maoism in terms of demeanor and dress, these images did succeed in conveying a certain amount of joy, although they were a far cry from the frivolous ladies of the advertising posters of earlier times.

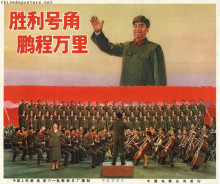

Battle songs to welcome spring, 1977

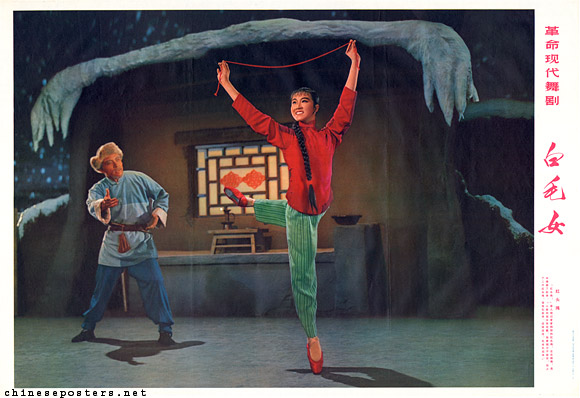

A special section of women-as-entertainers as they were used for propaganda purposes, consisted of posters based on scenes from the revolutionary model works that were supported by Jiang Qing during the Cultural Revolution. These posters, which mainly reproduced the more important themes from these operas, came in the form of ‘stills’ of noteworthy scenes, or in the form of multi-image, scene-by-scene renditions of the complete librettos of the plays.

Modern revolutionary ballet--The White-haired girl, 1973

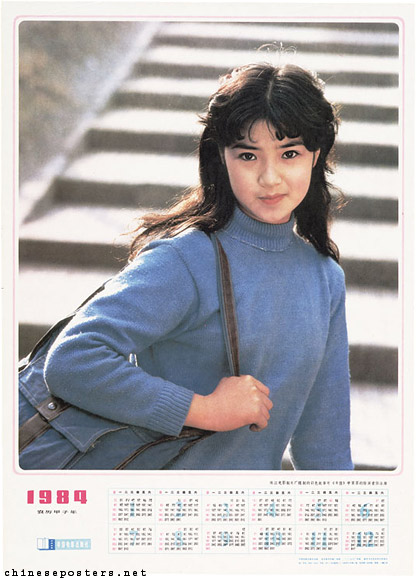

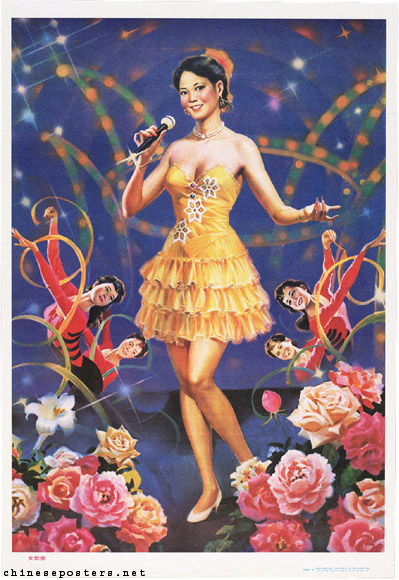

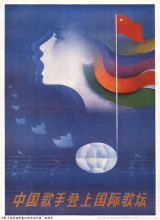

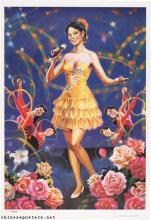

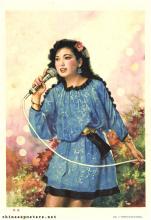

Once the modernization policies got underway, and the more or less conspicuous consumption of material goods became a way of defining one’s personality, the women represented in posters seemed to have returned to their earlier functions of providing entertainment and showing of. The erotic costumes worn by the ballerina’s in the classic Cultural Revolution ballet "Red Women’s Detachment" have been superseded, via demure pin-ups, by more explicit, if less titillating, images. An example of this complete turnaround can be found in the genre of the starlet poster. They became a fixture once the publication of cheap, single-sheet calendars featuring photographs of actresses started in the 1980s. Most of them were devoted to film and entertainment celebrities from Hong Kong and Taiwan. They have evolved gradually into forms that are comparable to the posters from the 1930s: Movie actresses and female television personalities have joined forces once more with advertising agencies to endorse products. The commodification of the female body has become a given in Reform China.

Ren Yexiang, 1984 calendar, 1983

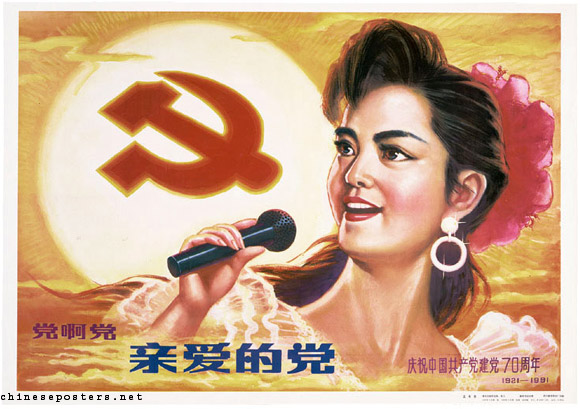

Reflecting the social realities of the reform era, which had given rise to mushrooming numbers of karaoke bars and massage parlors that usually employed good-looking young women to increase their turnover, women reappeared as entertainers on posters as well. In some cases, this was done with the explicit purpose of showing the target audiences that times had changed and that the desire to have fun was no longer to be frowned upon. Seen from another perspective, they made clear to the more conservatively oriented party officials what was deemed permissible, in order to avoid local crackdowns. In other cases, the CCP itself made use of such representations in an attempt to promote its own modernized image.

Chang Yuliang, "A Semiotic Analysis of Female Images in Chinese Women's Magazines", Social Sciences in China 31:2 (2010), 179-193

Tamara Perkins, "The Other Side of Nightlife: Family and Community in the Life of a Dance Hall Hostess", CHINA: An International Journal 6:1 (2008), 96-120

Zheng Tiantian, "Complexity of Life and Resistance: Informal Networks of Rural Migrant Karaoke Bar Hostesses in Urban Chinese Sex Industry", CHINA: An International Journal 6:1 (2008), 69-95