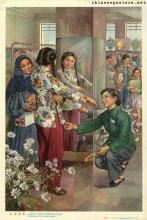

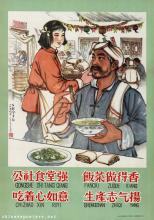

New view in the rural village, 1953

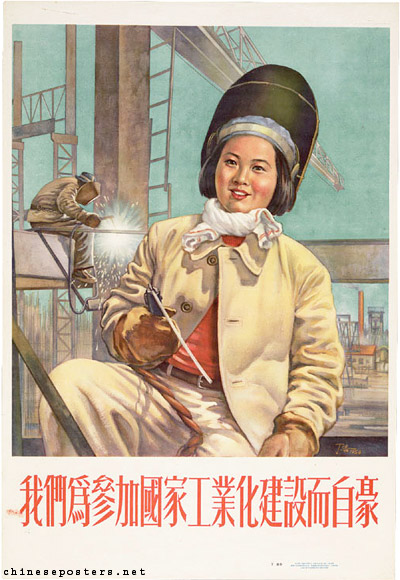

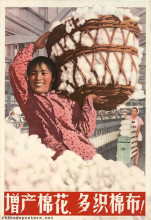

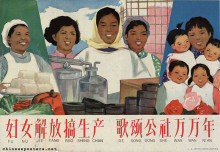

As a result of the double agenda pertaining to the emancipation of women, their participation in production, made visible in posters, was seen as one of the basic keys to bring about their liberation. Although posters of women working as welders or in other industrial activities do appear in the first one and a half decade of PRC-posters, most of their activities in this period remain located in agriculture.

We are proud to participate in the industrialization of the nation, 1954

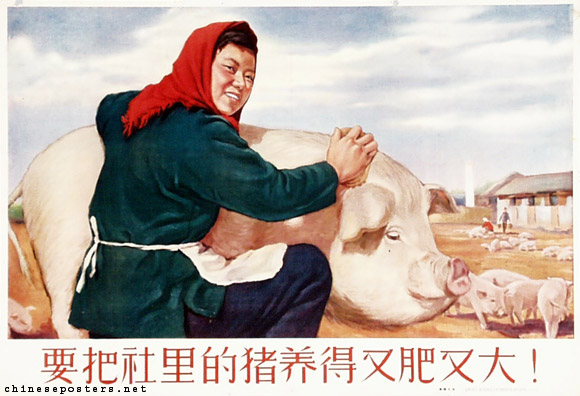

The hogs of the commune must be raised to be fat and big!, 1956

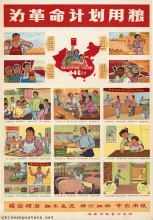

Their work in this sector ranged from working in the fields to raising livestock. During the campaigns where the setting up of sideline occupations was stressed, women in particular played an important role. The pervading message in these campaigns seemed to be that women still had plenty of time and energy left to engage in sideline activities after they had returned from spending a long day of backbreaking work in the fields.

Everybody strives to become a red standard bearer, commemorate 8 March, Women’s Day, 1960

By the late 1950s, when the policies designed to mechanize agriculture actually resulted in more mechanized equipment becoming available in the rural areas, the tractor was gradually introduced in posters. More often that not, posters showed how this piece of modern heavy-duty equipment was operated by a woman. The propaganda intention of the posters featuring these tractor girls seemed to be two-fold: it illustrated both the increases in the availability of farm machinery (and the successes of the Party in making all this possible) and the ability of women to actually operate these machines. In reality, however, the tractor operator usually was a man.

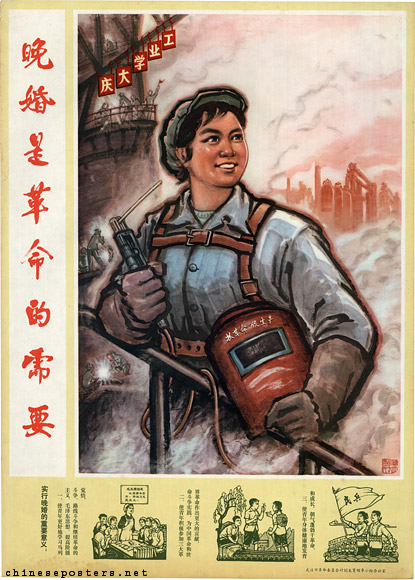

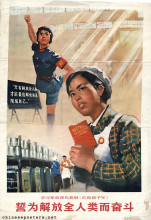

It is a revolutionary requirement to marry late, early 1970s

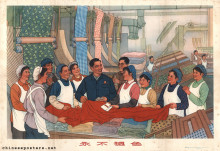

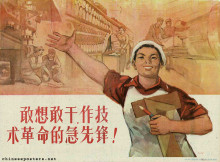

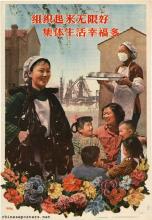

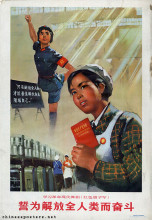

By the time of the Cultural Revolution, this trend of showing women taking on types of work generally associated with men was continued. In particular during the time when the movement to learn from the agricultural model commune of Dazhai was at its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, the muscular and energetic female team members, "imitation boys" (jia xiaozi) or "iron women" (tie nüren) working under commune leader Chen Yonggui, played an enormously influential function as role models for women. Iron girls inspired women to take on the most difficult and demanding tasks.

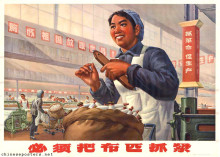

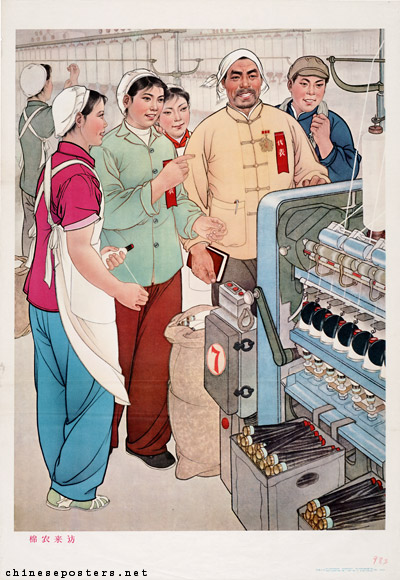

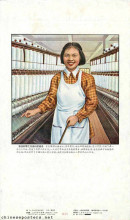

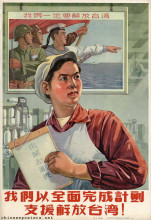

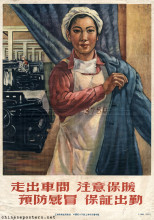

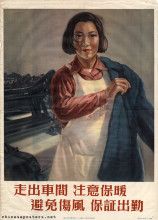

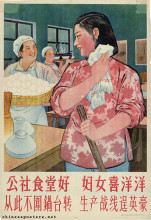

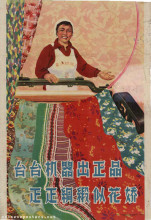

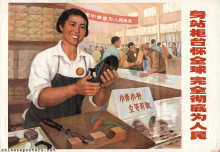

Generally speaking, then, women were confined to agriculture. Women in the forefront of industrial production only became a poster theme from the Great Leap Forward onwards. The trend was continued in Cultural Revolution posters, when women increasingly were represented while at work in factories. This was not necessarily limited to the textile industries, which were traditionally seen as typical places where women ought to work.

Drilling and training for the revolution, spinning and weaving for the people, 1974

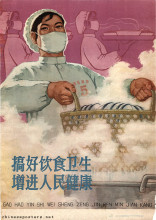

Although not explicitly visible in propaganda posters, female members of the urban work force were employed along unstated gender lines. Men usually were given technical jobs, and women were assigned non-technical, auxiliary and service jobs, regardless of their educational level.

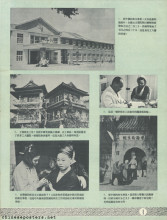

A cotton grower comes to visit, 1965

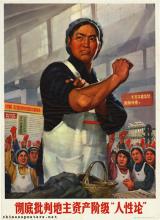

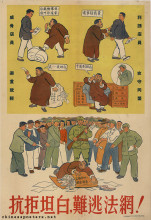

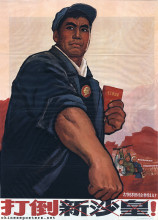

Thoroughly criticize the ‘theory of human nature’ of the landlord and capitalist classes, 1971

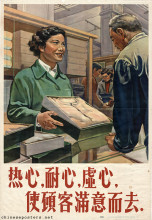

While women who in preceding decades often were depicted while engaging in typically masculine pursuits, strong pressure was exerted on them in the 1980s to return to their traditional, more ‘feminine’ roles of servants/waitresses, mothers and child-rearers. Paralleling the changes in thinking among the leadership, the need was no longer felt in official art to urge women to break through the traditional assumptions of gender inferiority.

The seaport of the nation, 1974

Instead of going out to work, they were exhorted more and more often to return to the stove and engage in home making. Such exhortations were voiced with renewed vigor in the late 1990s, when female workers who had been made redundant by the ever larger number of bankrupt State-owned industries were called upon to take on the responsibility for the domestic side of family life. A number of women on maternity leave even saw their legally granted period of absence extended indefinitely. On the other hand, the large numbers of women migrating from rural areas looking for employment in industry, the so-called ‘working girls’ (打工妹 dagongmei), constitute a relatively cheap female labor force that is exploited relentlessly in the name of economic development.

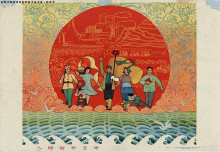

Move forward with great speed! To build up the nation, to defend the nation, 1978

More posters featuring working women:

Tina Mai Chen, "Female Icons, Feminist Iconography? Socialist Rhetoric and Women’s Agency in 1950s China", Gender & History, vol. 15, No. 2 (August 2003), pp. 268-295

Emily Honig and Gail Hershatter, Personal Voices - Chinese Women in the 1980s (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988)

Liu Meng & Lin Aibing, "Shichanghua yu funü diwei" [The evolution of the market and the position of women], Lin Aibing, Chen Liyun, Wang Xingjuan, Liu Meng (eds), Shehui biange yu funü wenti - laize funü rexiande sikao[Social transformation and the women’s question - Reflections based on the Women’s hotlines] (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 2001) [in Chinese]

Pun Ngai, "Becoming Dagongmei (Working Girls): The Politics of Identity and Difference in Reform China", The China Journal, No. 42 (July 1999)

Wang Zheng, "Gender, employment and women’s resistance", Elisabeth J. Perry & Mark Selden (eds), Chinese Society - Change, Conflict and Resistance (London, etc.: Routledge, 2000), pp. 62-82

Yu Fawu (ed.), Xiagang zhigong laodong guanxi wenti toushi [Perspectives on questions relating to labor relations of unemployed workers] (Beijing: Jingji kexue chubanshe, 2000) [in Chinese]

![The great significance of implementing [the policy of] marrying late and birth control](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/e15-180.jpg?itok=cd_PADVQ)