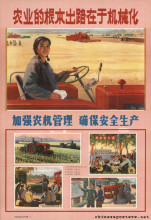

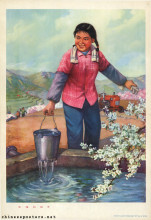

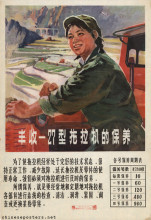

From the early 1950s on, the female tractor driver was one of the most frequently seen symbols of Chinese socialist modernity. Known as the nüjie diyi (女界第一) model workers, the ‘female-kind-first’, they were part of the group of ‘the first’ women to be trained in work involving heavy machinery. Liang Jun (below), one of China’s first female tractor drivers, was introduced to Chinese audiences in 1953 in posters, anthologies and school texts. She even appeared on the 1 yuan banknotes, issued in 1962.

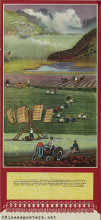

The occupational choice of many of these first women to become tractors drivers had been influenced very much by the many photographs of Soviet women taking part in production, and by Soviet films about mechanized agriculture that circulated in China in those days. Male Soviet advisors and Soviet models also played an important role in the actual training programs on Chinese soil.

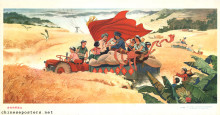

In the many (auto-) biographical materials devoted to these ‘New women’ in the early 1950s, a pattern clearly emerges. First, the female body needed to be strengthened, in order to be physically up to this new type of work that bore no semblance to the labor more tradionally associated with women. Secondly, once the workings of the equipment were mastered, a symbiotic relationship emerged between the body and the machinery. By not giving in to physical discomfort, women liberated themselves from historical, familial and economic oppression.

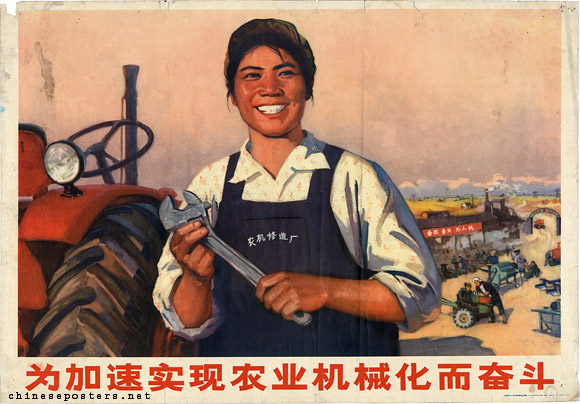

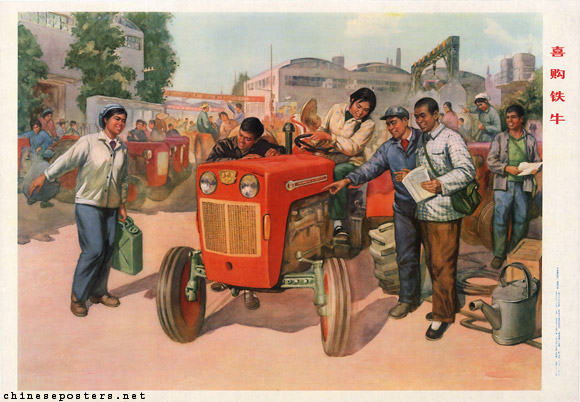

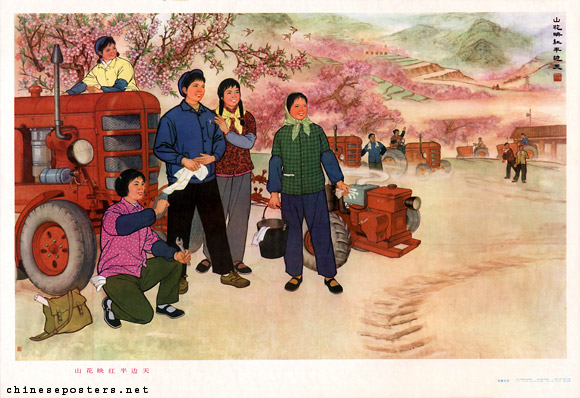

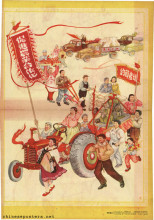

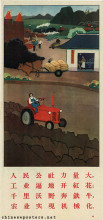

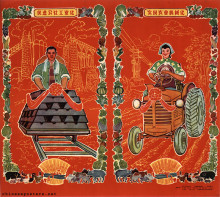

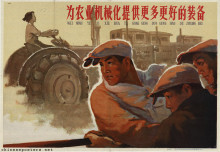

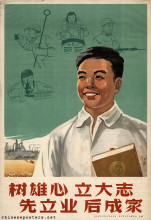

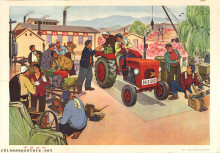

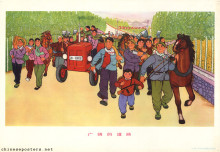

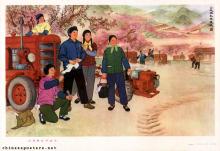

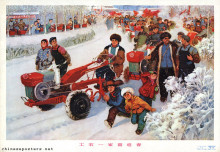

Obviously, the location of the ‘new woman’ in propaganda posters was in the working class and in close proximity of equipment. She was no longer a mere country girl (农村姑娘, nongcun guniang) but had become a woman-worker (劳动妇女, laodong funü) by taking part in training and mastering machinery. She represented the group of new productive members of society that had been proletarianized and had broken out of the confines of domestic work.

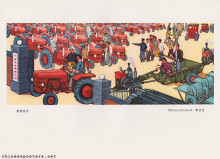

Struggling to speed up the realization of mechanized agriculture!, 1971

The fact that the tractor girls more often than not wore white shirts strengthened the message that they had joined the proletariat. The white shirt, with its connnotation of education, stood for the ideal of the advanced red and expert worker. Even when a tractor girl was situated as laboring in the countryside, the white shirt suggested external knowledge that helped to improve labor efficiency.

Although these ‘first women’ were largely undifferentiated in physical appearance from the idealized male body of the period, the qualifyer ‘female’ rarely failed to appear in the slogan, thus reminding the reader that women could and should assume such proportions and occupations. Equally important, however, was the message that socialism demanded such reshaped bodies.

These constant visual reminders of women taking part in work traditionally seen as within the male domain served an obvious purpose, even later on. When Liang Jun entered the tractor driver program in Heilongjiang in 1948 as the only woman in the group, she encountered resistance from classmates and teachers. The hostile environment only inspired her to persevere in her unconventional choice of work.

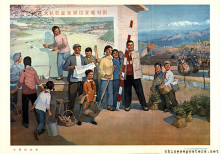

Mountain flowers shine red on the new women, 1974

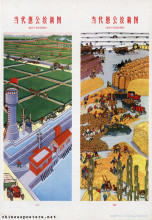

The images made a number of things clear: a woman should take part in production, whether in the factory or in agriculture, and in doing so, should not be excluded from operating machinery. Moreover, they firmly placed the woman in the proletariat. And finally, they indicated that leadership positions should be as open to women as to men. In reality and in practice, however, this largely remained utopian.

Learning English sentences by pictures, 1979

As in industry and agriculture, the operation of tractors and other mechanized equipment by and large remained within the domain of the male workers. Women were confined to operating machines used for planting rice shoots and threshing, and to the machinery in textile factories. The urgency with which female participation in mechanization intially was represented gave way to an idealized reality where women operated non-essential machines.

Little Red Guard tea stop, 1974

Tina Mai Chen, "Female Icons, Feminist Iconography? Socialist Rhetoric and Women’s Agency in 1950s China", Gender & History, vol. 15, No. 2 (August 2003), pp. 268-295

Tina Mai Chen, "Proletarian White and Working Bodies in Mao’s China", positions, vol. 11, no. 2 (Fall 2003), pp. 361-393

Daisy Yan Du, "Socialist Modernity in the Wasteland: Changing Representations of the Female Tractor Driver in China, 1949-1964", Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 29, no.1 (Spring 2017), pp. 55-94.