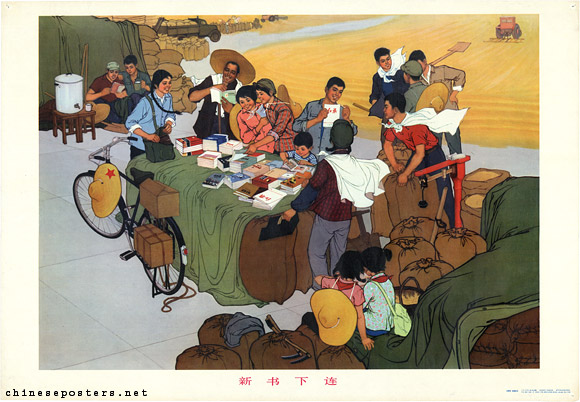

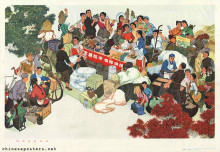

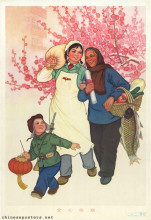

New books come down to the fields, 1974

Entrepreneurs, of course, always have been considered politically problematic in China. The traditional Confucian class division of society saw the entrepreneurs, or merchants, as less desirable than intellectuals, peasants, workers or even soldiers. This struck a chord with the Marxist-Leninist type of class analysis practiced by the CCP, which considered entrepreneurs, or merchants, or capitalists, as exploiters of the urban and rural working classes.

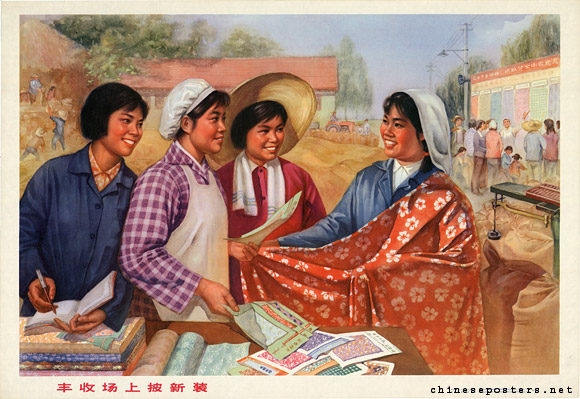

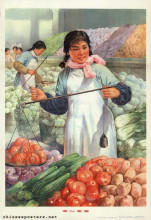

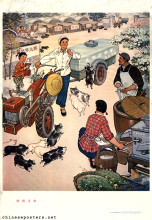

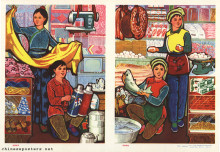

Spreading out new clothes on a bumper harvest market, 1976

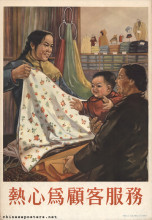

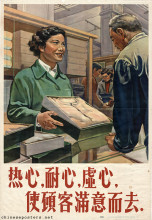

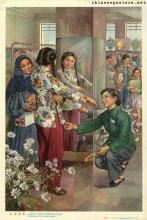

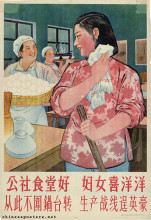

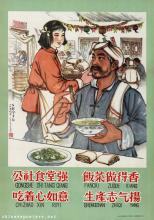

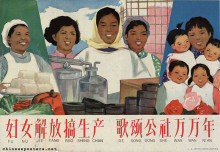

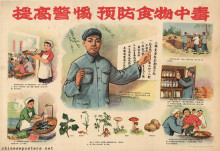

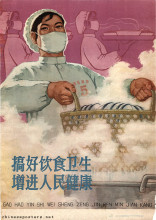

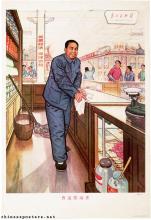

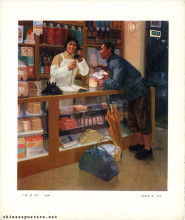

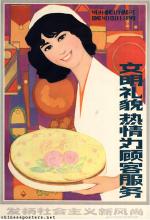

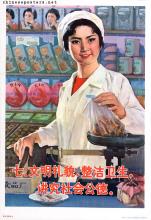

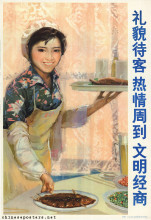

Even though many women might have been active as stall keepers or small shop owners, in short as entrepreneurs, before the founding of the PRC, this was definitely not seen as a desirable occupation after 1949. Despite the claims that women had been liberated, their economic activities should take place within what was politically acceptable. At best, they were allowed to function as shop assistants or waitresses, in which capacities they often appeared in poster materials in the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s. Although employed in what can be termed the service sector, this did not mean that these women could be bossed around. As a matter of fact, during the Cultural Revolution in particular, rude behavior towards service personnel was seen as an expression of feudal thought. Rude behavior by service personnel against customers, on the other hand, was seen as the result of having been liberated, and having shaken off the slave mentality. Being insulted and yelled at became the norm for many Chinese shoppers.

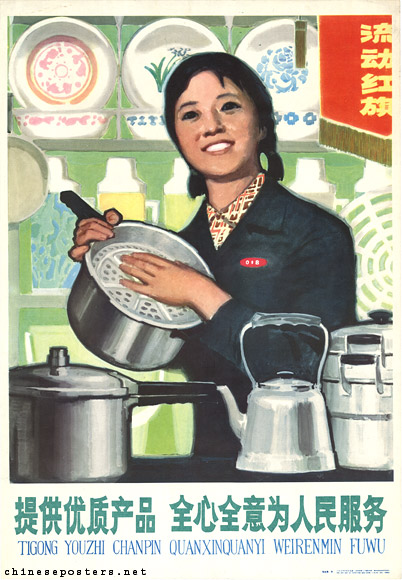

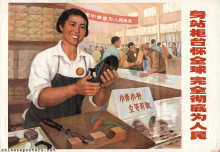

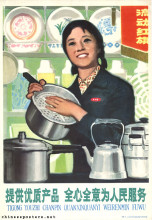

Supply high grade products, serve the people wholeheartedly, 1978

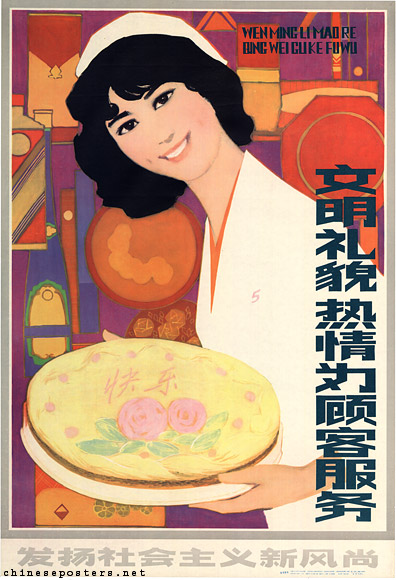

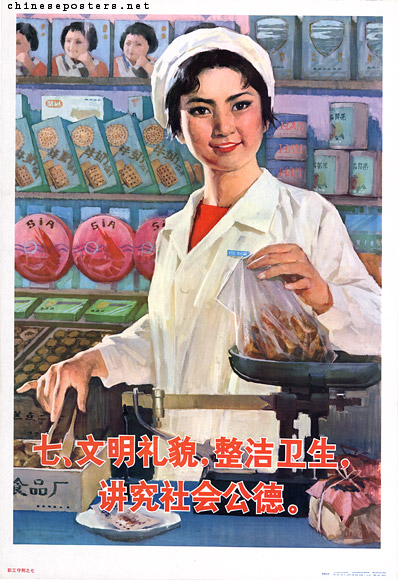

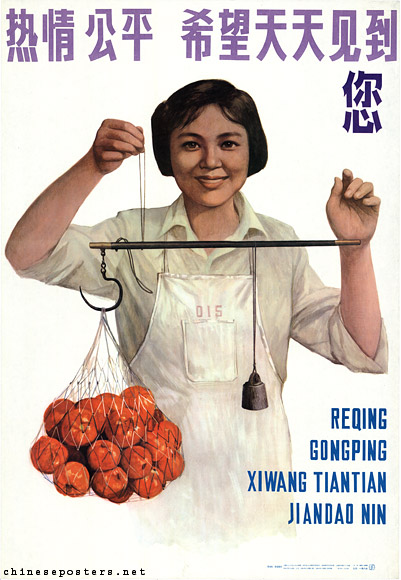

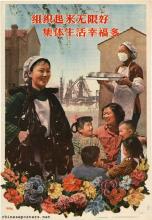

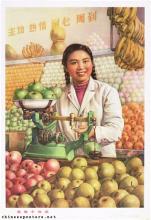

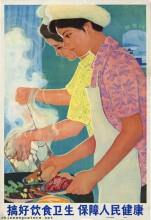

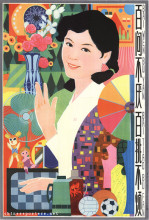

Women thus became the logical addressees of the posters that accompanied the numerous courtesy-campaigns of the early 1980s that attempted to restore some level of civility to society. These posters featured women who worked in the service trades and exhorted them to be more user-friendly and to adopt a fair attitude towards customers. The various women who were portrayed while being active in tertiary sector work, whether as sales persons or in other capacities, do not give the impression of being harassed by the demands of their customers or charges, and as such contrasted sharply with reality. Indeed, their relaxed posture no doubt had to contribute to the civilized and courteous behaviour that was sought through their use as carriers of that specific message.

Serve customers in a cultured, civilized and enthusiastic manner--Develop new socialist habits, 1982

Cultured and civilized, tidy and hygienic, practice social morality, 1983

Only towards the 1990s, and very much echoing the increasingly frequent social phenomenon of becoming a private entrepreneur, entrepreneurial women on posters replaced the service workers in the tertiary sector. As a matter of fact, average urban women started to consider jobs in the service sector as demeaning, as these were increasingly taken up by the large masses of migrant laborers moving into the cities from the poor countryside. In particular after Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 Southern inspection tour, starting one’s own business, or xiahai (下海, ‘to jump into the sea [of doing business]’), became extremely popular. By that time, however, posters had ceased to function as important media to publicize this fundamental change in occupational roles open to women.

Minglu Chen, "The way to entrepreneurship: female entrepreneurs’ education and work experience in Jiaocheng County, Shanxi Province, the People’s Republic of China", PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies 3:2 (2006)