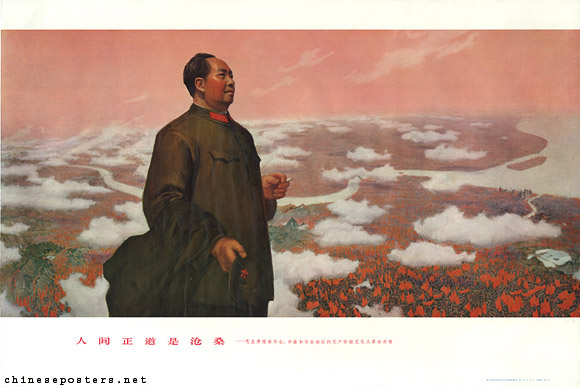

Man’s world is mutable, seas become mulberry fields, 1967

During the 1967-1968 Red Sea Movement, the whole nation was called upon to paint Mao portraits and cover the nation with them; this included professional and amateur artists alike. The Red Sea Movement was not necessarily meant to make people to engage in specific behavior; rather, it intended to turn the Leader into an embodiment of the Revolution.

There is no better way to illustrate this movement than with the famous fresco turned painting turned propaganda poster entitled ’Man’s world is mutable, seas become mulberry fields: Chairman Mao inspects the situation of the Great Proletarian Revolution in Northern, South-Central and Eastern China’ (Renjian zhengdao shi cangsang - Mao zhuxi shicha Huabei, Zhongnan he Huadong diqude wuchan jieji wenhua da geming xingshi, 人间正道是沧桑-毛主席视察华北、中南和华东地区的无产阶级文化大革命形势), published in 1967. The title quotes the last line from Mao’s poem ‘The People’s Liberation Army Captures Nanking’, from April 1949. It is a reference to a world in which everything is changing. Foregrounding the figure of Mao hovering over the nation, it represents the type of propaganda designed during the movement.

According to Zheng Shengtian, one of the three artists involved in its creation, it originally was painted in 1967 as a unique fresco outside of the Hangzhou Steel Factory in Hangzhou. Zheng, although considered ‘a bourgeois intellectual amenable to reform’ at the time and therefore of questionable political trustworthiness, was made responsible for the total composition. The other artists who participated, Zhou Ruiwen and Xu Junxuan, were considered more dependable ideologically; they were ordered to paint Mao’s face and body, respectively. Despite their different political labels, all three agreed on the bold way in which the Change hinted at in Mao’s poem needed to be visualized: they opted for a romanticized style that was not very common at the time. Moreover, they employed stylistic elements from traditional landscape painting (shanshui 山水) that was then under attack for being a traditional art form. In a 2016 interview, Zheng recounts how he painted

...Mao standing above the clouds, where he could see all of China from the sky. And the ground was covered with red flags. On the ground, you can recognize cities; I made Hangzhou the largest [...] Shanghai is there, and you can also see Jinggangshan and Shaoshan in Hunan, where Mao was born.

Hangzhou

Shaoshan

Zheng was partial to Hangzhou; the city at the time was considerably smaller than Shanghai. According to Zheng, hundreds of thousands of copies were made and distributed in journals and magazines; they were reprinted as large-format posters, or in smaller formats. It found its way onto biscuit tins, mirrors, and postage stamps. It was reproduced on huge billboards. Although it resonated with the popular audience, when a friend of Zheng showed it to Mao’s wife Jiang Qing in May 1968, she expressed her dislike for it. She interpreted Mao’s 1967 trip to which the image alluded as an implicit criticism of her own policies. According to Zheng, Jiang thought that Mao’s chin had not been painted so well, and remarked that

[P]eople may like this painting, but I don’t. I don’t think Mao’s likeness is strong, and Mao never carried a coat like this.

Mao’s chin

It was only later, after the end of the Cultural Revolution when much pertinent documentation about the period was released, that Zheng and his fellow artists understood how Jiang’s feeling of being criticized by Mao had been the reason behind the sudden drop in high-level support for an image that generally seemed so well-liked.

Thomas J. Berghuis, ‘History and community in contemporary Chinese art’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 1:1 (2014)

Mao Zedong, ‘The People’s Liberation Army Captures Nanking -- a lü shih, April 1949’, www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/poems/poems19.htm

Zheng Shengtian, ‘Art and Revolution: Looking Back at Thirty Years of History’, in Art and China’s Revolution, ed. Melissa Chiu and Zheng Shengtian (Asia Society/Yale University Press, 2009)

Zheng Shengtian, ‘China – The Red Sons: A Screening and Conversation with Zheng Shengtian’, China Institute, New York, 3 May 2016, www.aaa-a.org/programs/china-the-red-sons-a-screening-and-conversation-with-zheng-shengtian/  )

)