To go on a thousand ‘li’ march to temper a red heart, 1971

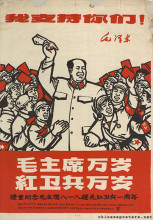

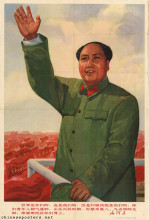

In the Summer of 1966, when the Cultural Revolution got underway, many emerging groups of Red Guards felt repressed in their revolutionary fervor by school and university authorities who attempted to keep the situation under control. The Red Guards wanted to go to Beijing and Chairman Mao to look for justice and sympathy, and to share their experiences with other groups. This formed the beginning of a period of revolutionary networking (chuanlian 串联) which lasted from August 1966 until March 1967. While many came by train and car, thus overburdening the transport infrastructure, those who walked all the way to Beijing were considered to be truly demonstrating their revolutionary credentials.

Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou together with us, 1977

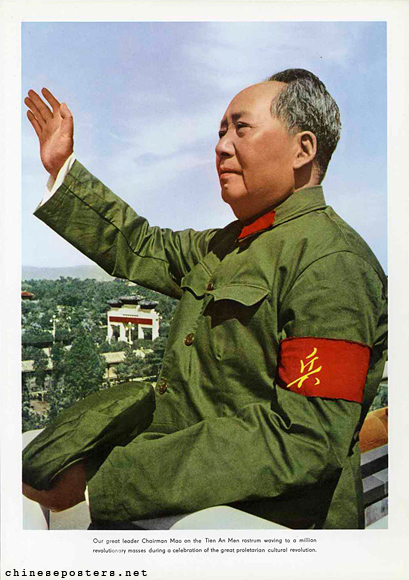

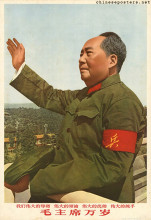

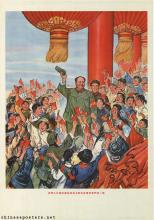

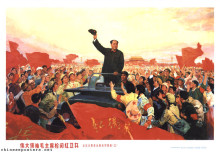

Beijing was the center of the networking movement. Millions of Red Guards piled into the city. Classrooms and university dormitories were turned into reception stations. The networkers received free meals, for they were "guests of Chairman Mao". The Red Guards also were given free transport passes within the city and free admission to parks. The greatest reward, of course, was to catch a glimpse of Mao. To this end, ten "audiences" were organized, on 18 and 31 August, 15 September, 10 and 18 October, and 3, 10, 11, 25 and 26 November 1966, where Mao ‘inspected’ millions of Red Guards. These mass receptions contributed to the further worship and deification of Mao, and helped him to vanquish local political and Party resistance to the Cultural Revolution.

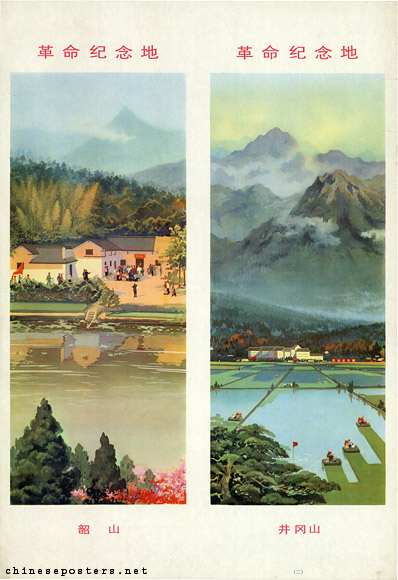

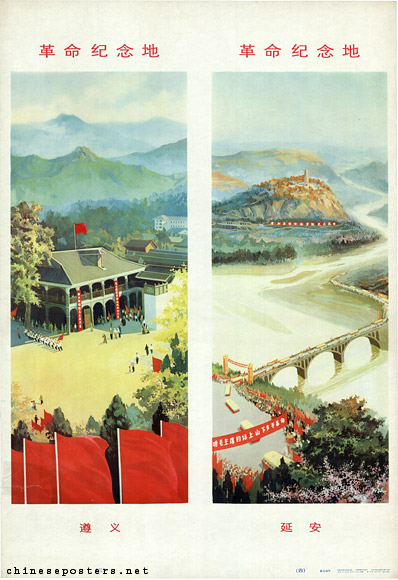

After having visited Beijing, the Red Guards swarmed out all over the country. Some went to Mongolia, others to Xinjiang, or Guilin, or Shanghai. But the places where the Long March had passed through provided great drawing power for many youngsters who considered themselves to be on a Long March of their own. These destinations, so-called "Memorial Places of Revolutionary History", included Shaoshan (Mao’s birth place), Jinggangshan (the cradle of the Communist Party), Zunyi (where Mao had become the leader of the Party), Luding Bridge (where a heroic crossing over the Dadu River took place), and Yan’an (the revolutionary base area where the Party’s policies had emerged and matured during the 1930s and 1940s).

Commemmorative places of the revolution - Shaoshan, Jinggangshan, 1974

Commemmorative places of the revolution - Zunyi, Yan’an, 1974

However, all this travelling of millions of people led to an enormous congestion. By the end of 1966, the Central Committee sent out calls to terminate the movement, and the Red Guards were urged to return home and continue conducting the Cultural Revolution there. By February 1967, all reception stations and liaison offices were closed. The movement was seen as having served its political purpose. For many youngsters, however, this had been the first time they had been able to travel and see their country.

Gao Yuan, Born Red - A Chronicle of the Cultural Revolution (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987)

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Li Zhensheng, Red-Color News Soldier - A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey through the Cultural Revolution (London: Phaidon Press, 2003)

Lu Xing, Rethoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution - The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture and Communication (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2004)

Rudolf G. Wagner, "Reading the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Peking: The Tribulations of the Implied Pilgrim", Susan Naquin & Chün-fang Yü (eds), Pilgrims and Sacred Sites in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992)

Wu Hung, Remaking Beijing - Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005)

Yan Jiaqi & Gao Gao (translated & edited by D.W.Y. Kwok), Turbulent Decade - A History of the Cultural Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1996)

Yang Kelin (ed.), 文化大革命博物馆 [Museum of the Cultural Revolution] (Hong Kong: Dongfang chubanshe youxian gongsi, Tiandi tushu youxian gongsi, 1995)