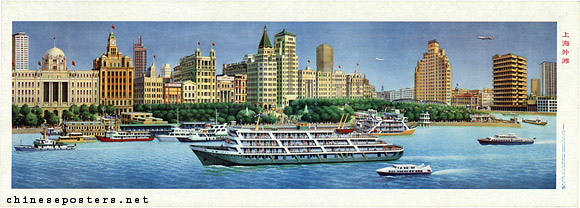

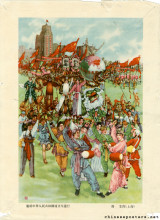

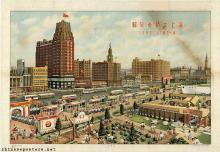

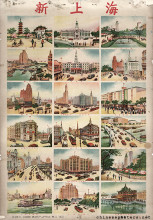

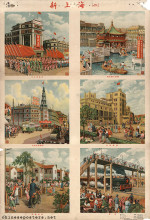

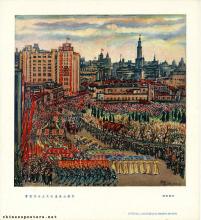

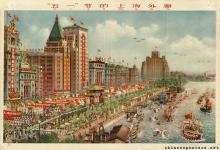

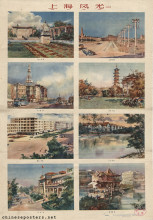

Shanghai’s Bund on a festive day, 1963

Shanghai (上海), the vibrant metropolis with over 25 million inhabitants, the world’s largest port and a global hub for finance and technology, was a relatively small town until around 1840. After the Opium Wars and the Treaty of Nanking of 1842, the city became a ‘trade port’, where foreigners were allowed to live and work. The British, French, American and Japanese traders and businessmen moved in and began to exploit the city’s favorable location near the mouth of the Yangzi river and the sea. They lived under their own national laws, protected by their own police forces. Around 1900, the city began to grow rapidly, with large numbers of peasants trying to find work in the harbor and factories. Living conditions were terrible, wages were low, the oppression of the workers by the foreign owners and managers was fierce. In Shanghai, China’s first urban proletariat came into being. The city became a nucleus for radical political movements.

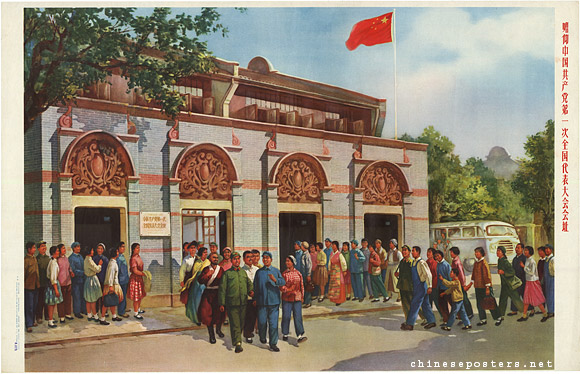

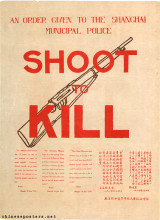

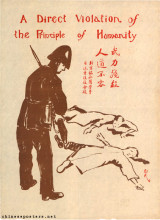

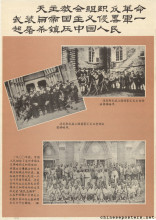

On 23 July 1921, the Chinese Communist Party was founded and held its First National Congress in Shanghai. Mao Zedong was among the delegates.  The building where this took place was preserved and became a museum, effectively a place of pilgrimage, under Communist rule. Other important events connected with the history of the Communist Party were the incidents on 30 May 1925, when police forces under British command opened fire on a Communist-supported demonstration on Nanjing Lu, killing thirteen, and giving rise to the ‘May Thirtieth Movement’, and the killing of thousands of communists in April 1927 by thugs under orders of Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Nationalist Party (Guomindang).

The building where this took place was preserved and became a museum, effectively a place of pilgrimage, under Communist rule. Other important events connected with the history of the Communist Party were the incidents on 30 May 1925, when police forces under British command opened fire on a Communist-supported demonstration on Nanjing Lu, killing thirteen, and giving rise to the ‘May Thirtieth Movement’, and the killing of thousands of communists in April 1927 by thugs under orders of Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Nationalist Party (Guomindang).

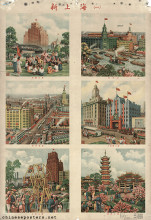

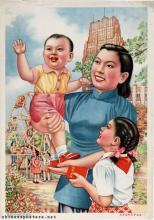

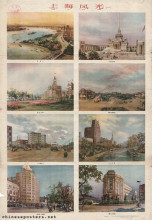

In the West, Shanghai was better known for its other face: that of a decadent, exotic, glamorous, fast-paced metropolis, where fortunes were quickly made in business and lost even faster at the racecourse, where jazz-bands played and pretty girls danced all night - a playground for the rich, the ‘Paris of the East’. The Bund, along Huangpu river, represented Shanghai’s wealth, with its banks and commercial buildings - most of them built by Westerners who had made their money in the opium trade. Shanghai boasted the largest department stores and the most luxurious hotels of the East. The ‘Shanghai Style’ in architecture, arts, design and fashion blended Eastern and Western elements, especially Art Deco. As for posters, Shanghai was home to the largest printing, advertising and publishing companies, both for traditional New Year prints and commercial advertising posters. Most famous were the calendar posters with elegant Chinese women, often advertising cigarettes, designed by excellent artists such as Zheng Mantuo, Xie Zhiguang, Ni Gengye, Jin Meisheng and Hang Zhiying, in whose studio Li Mubai and Jin Xuechen worked.

In the West, Shanghai was better known for its other face: that of a decadent, exotic, glamorous, fast-paced metropolis, where fortunes were quickly made in business and lost even faster at the racecourse, where jazz-bands played and pretty girls danced all night - a playground for the rich, the ‘Paris of the East’. The Bund, along Huangpu river, represented Shanghai’s wealth, with its banks and commercial buildings - most of them built by Westerners who had made their money in the opium trade. Shanghai boasted the largest department stores and the most luxurious hotels of the East. The ‘Shanghai Style’ in architecture, arts, design and fashion blended Eastern and Western elements, especially Art Deco. As for posters, Shanghai was home to the largest printing, advertising and publishing companies, both for traditional New Year prints and commercial advertising posters. Most famous were the calendar posters with elegant Chinese women, often advertising cigarettes, designed by excellent artists such as Zheng Mantuo, Xie Zhiguang, Ni Gengye, Jin Meisheng and Hang Zhiying, in whose studio Li Mubai and Jin Xuechen worked.

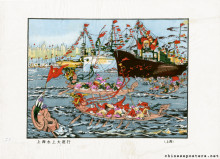

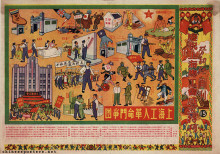

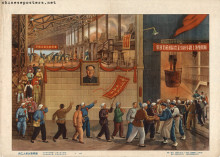

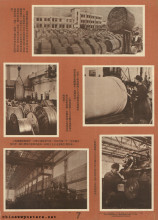

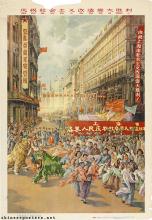

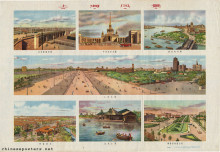

After the communist takeover in 1949, Shanghai was ‘purged’ - not just of crime, prostitution, drugs and private enterprise, but also of its cosmopolitan style and Western influences. But the poster design and publishing industry remained. Private commercial companies were merged into the East China People’s Publishing House (Donghua renmin chubanshe - 东华人民出版社), later renamed as Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House (Shanghai renmin meishu chubanshe - 上海人民美术出版社). This would remain China’s largest and most important poster publishing house for decades. What also remained were the landmark buildings. With their Western style and connections to capitalism and decadence, they could not be used as prominent subjects on propaganda posters. But how to depict Shanghai without these buildings? So they became a backdrop for correct behaviour and political events: a parade to celebrate the victory of ‘socialist transformation’, May Day celebrations, workers and foreign delegates strolling along the Bund, an anti-American demonstration.

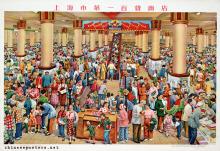

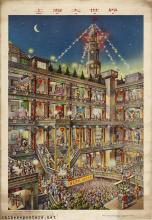

Shanghai’s famous racecourse became the People’s Park, with a playground for children. Some of the famous capitalist enterprises from the 1920s and 1930s re-opened under state control. The former Sun Company became the ‘Shanghai No.1 Department Store’. Its original escalator, Shanghai’s first and for a long time only operational public one, was an attraction in itself. The Great World Entertainment Center, a multi-storied building with scores of rooms for all kinds of performances, gambling, fortune-telling, etc., started business again in 1954. The entertainment now was strictly in line with the puritanical demands of the Party.

Still, Shanghai was perceived as a decadent city, corrupting the true revolutionary spirit, and that was one of the reasons that the central government kept the city on a tight leash. To show how to deal with these dangers, the soldiers of the Eighth Company of the PLA were put forward as a role model. In 1949, the Eighth Company was stationed in an old warehouse on Nanjing Road (Nanjing lu - 南京路), Shanghai’s busiest shopping street. And here they stayed, patrolling for acts of crime, bravely resisting the tempations around them, wearing their old uniforms until they were absolutely worn out, mending the soles of their shoes themselves. Their image on posters is that of an armed, alert soldier detached from the glitter and glamour surrounding him. In 1959 a national campaign started to ‘emulate the Good Eighth Company of Nanjing Road’, which resulted in posters, songs, films, a play, and even a poem by Mao Zedong.

During the Cultural Revolution, Shanghai showed its radical side again. It was here that Mao withdrew to after being severely criticized by his peers for the failure of the Great Leap Forward; it was here that Jiang Qing, who knew the city well from her years as an actress in the 1930s, launched her first attacks on the arts scene, and formed what would become the Gang of Four. In January 1967, Mao instructed the rebel factions in Shanghai to seize power from party and government organizations. During what was to become known as the "January Storm", rebel organizations in the whole country followed Shanghai’s example, throwing China into a state of great chaos. Once the various Red Guard factions had seized power, they had to be combined into a single administrative unit. This new governing body, with democratically elected office-holders, was to resemble the Paris Commune of 1871, and became known as the Shanghai People’s Commune. The Commune was to be formed officially on 26 January, but due to a number of reasons, this was delayed until 5 February, causing the Shanghai People’s Commune to become obsolete: another organizational model, the Revolutionary Committee, which was based on a "three-way alliance of Red Guards, Party cadres and army men", was preferred by the Centre.

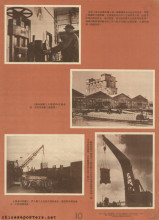

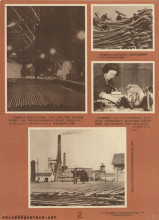

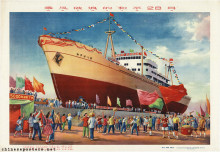

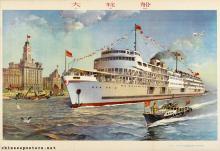

Shanghai was one of the last cities that was to profit from the economic liberalizations that were introduced after the Cultural Revolution. Because of its decadent and radical past, it remained under suspicion until well into the 1980s. But once given the opportunity to develop, the city regained its position as China’s most important trading port. The shipbuilding industry recovered, the shopping streets came to life again. Pudong (浦东), the area on the eastern bank of the Huangpu river, was declared a Special Economic Zone in 1990. That meant less bureaucracy, lower taxes, and more possibilities for foreign investments and joint ventures with Western companies. What had been an area of old wharves, old factories and farmlands became the world’s largest building site, where one could see skyscraper after skyscraper rising up at breakneck speed. One of the signature buildings is the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, 457 meters high. Pudong became China’s showcase of the future, to be admired from the walking boulevard along the old Bund. Jiang Zemin, one of the highest local party leaders during much of this period, succeeded Deng Xiaoping to become President of the People’s Republic in 1989. The pre-war competition with Hong Kong for preeminence as a financial and business center is slowly but surely tilting in Shanghai’s favor. The city hosted the 2010 World Expo, which was not just a symbolic milestone. Shanghai has become an example for China - perhaps now more than ever.

Yomi Braester, ""A Big Dying Vat". The Vilifying of Shanghai during the Good Eighth Company Campaign", Modern China 31:4 (2005), 411-447

Yomi Braester, "The Political Campaign as Genre: Ideology and Iconography during the Seventeen Years Period", Modern Language Quarterly 69:1 (2008), 119-140

Szu-Wei Chen, "The rise and generic features of Shanghai popular songs in the 1930s and 1940s", Popular Music 24:1 (2005), 107–125

Sherman Cochran (ed.), Inventing Nanjing Road: Commercial Culture in Shanghai, 1900-1945 (Cornell East Asia Series) (Ithaca: Cornell East Asia Series No. 103, 1999)

Andrew Field, Shanghai’s Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Urban Politics, 1919-1954 (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010)

Andrew Field, Shanghai Nightscapes: The Nocturnal Biography of a Global Metropolis, 1912-2012 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015)

Denise Y. Ho, Curating Revolution – Politics on Display in Mao’s China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018)

Xuelei Huang, "Deodorizing China: Odour, ordure, and colonial (dis)order in Shanghai, 1840s–1940s", Modern Asian Studies 50:3 (2016), 1092–1122

Ellen Johnston Laing, Selling Happiness: Calendar Posters and Visual Culture in Early Twentieth-Century Shanghai (Honolulu: University of Hawai'ï Press, 2004)

Hanchao Lu, "Becoming Urban: Mendicancy and Vagrants in Modern Shanghai", Journal of Social History 33:1 (1999), 7-36

Hanchao Lu, "Bourgeois Comfort under Proletarian Dictatorship: Home Life of Chinese Capitalists before the Cultural Revolution", Journal of Social History (2018), 1–27

Scott Minick & Jiao Ping, Chinese Graphic Design in the Twentieth Century (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 1990)

Wenming Xiao & Yao Li, "Building a ‘Lofty, Beloved People’s Amusement Centre’: The socialist transformation of Shanghai’s Great World (Dashijie) (1950-58)", Modern Asian Studies (2020), 1-42