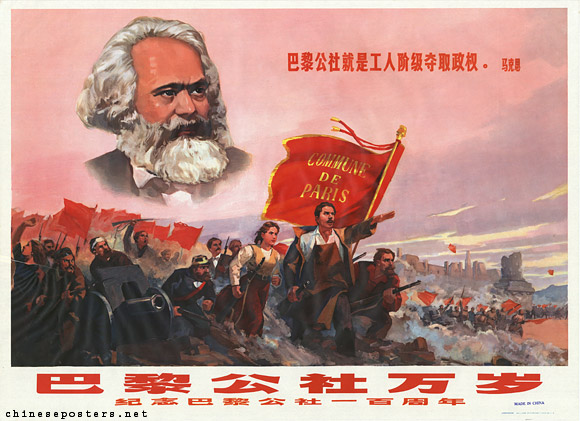

In January 1967, Mao instructed the rebel factions in Shanghai to seize power from party and government organizations. During what was to become known as the "January Storm", rebel organizations in the whole country followed Shanghai's example, throwing China into a state of great chaos. Once the various Red Guard factions had seized power, they had to be combined into a single administrative unit. This new governing body, with democratically elected office-holders, was to resemble the Paris Commune of 1871.

Long Live the Paris Commune--Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Paris Commune, 1971

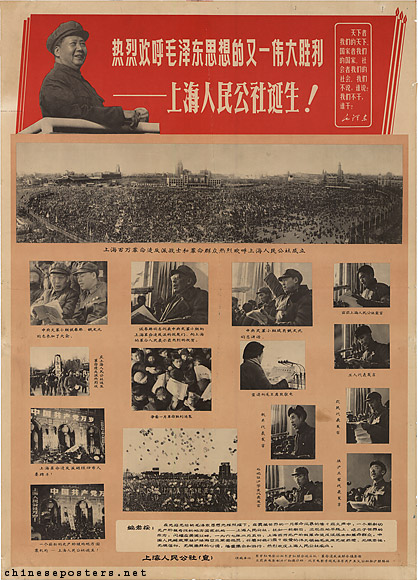

Zhang Chunqiao, member of the Gang of Four and the leader of the Workers' General Headquarters, the dominant faction in Shanghai, was supported in his bid for power by the Cultural Revolution Central Group in Peking. He saw the January Storm as an opportunity to clamp unity on Shanghai and grasp power in the process. He would head the Shanghai People's Commune (上海人民公社, Shanghai renmin gongshe), assisted by his Gang-member Yao Wenyuan. The Commune was to be formed officially on 26 January, but due to a number of reasons, this was delayed until 5 February. This delay caused the Shanghai People's Commune to become obsolete: another organizational model, the Revolutionary Committee, which was based on a "three-way alliance of Red Guards, Party cadres and army men", was preferred by the Centre.

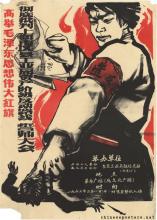

There is irrefutable evidence that the rotten heads of the United Departments plotted..., 1967

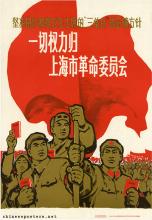

On 24 February, the Commune was officially suspended and renamed as the Shanghai Revolutionary Committee by Mao himself, who declared that it was too early to set up a Commune. Zhang Chunqiao remained in charge. By 5 September 1968, Revolutionary Committees were set up in all China, "coloring the entire country red". The Committees were abolished in 1979 and replaced by people's governments at all levels.

Beat the "United" countercurrent - defend the Shanghai Revolutionary Committee to the death!, 1967

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Neale Hunter, Shanghai Journal - An Eyewitness Account of the Cultural Revolution (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1988 [repr. 1969])

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1995)

Elisabeth J. Perry, "From Paris to the Paris of the East and Back: Workers as Citizens in Modern Shanghai", Comparative Studies in Society and History 41:2 (1999), 348-373

Michael Schoenhals (ed.), China’s Cultural Revolution, 1966-1969 - Not A Dinner Party (Armonk: M.E Sharpe, 1996)

Andrew G. Walder, Chang Ch’un-ch’iao and Shanghai’s January Revolution (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies/The University of Michigan, 1978)