Going to live and work in a production team to wage revolution, 1969

The May 7 Cadre Schools were set up in late 1968, in accordance with Mao Zedong’s May 7 Directive, which was released on May 7, 1966. In this directive, Mao suggested setting up farms, later called cadre schools, where cadres and intellectuals, "sent down" from the cities, would perform manual labor and undergo ideological reeducation. "Sending down" cadres was first put into practice during the Great Leap Forward Movement in 1958. Cadres would take turns to go the villages or grass-roots levels to gain first-hand experience in productive work.

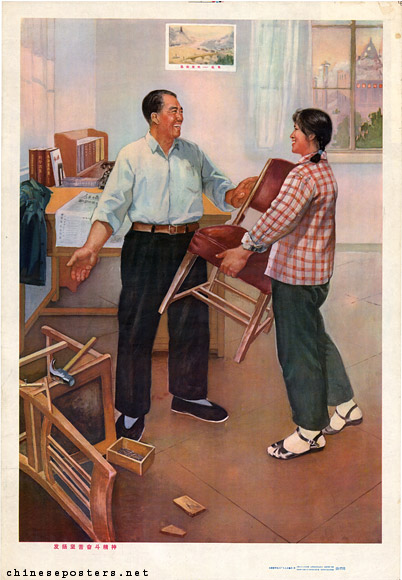

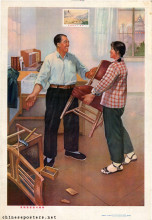

Develop the spirit to wage bitter struggle, 1975

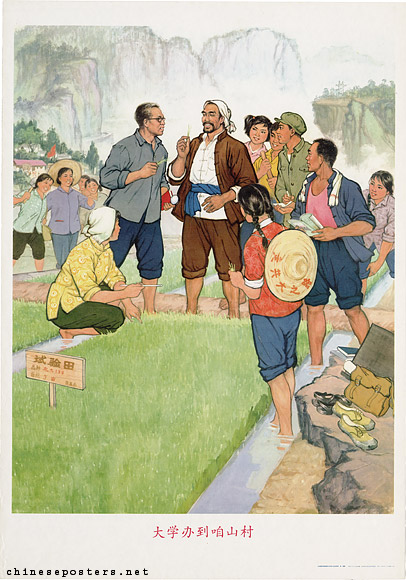

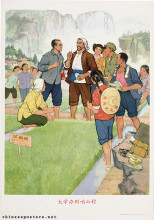

The university takes care of our mountain village, 1976

During the Cultural Revolution, "transferring cadres to lower levels" became a favored method to remove unyielding cadres and intellectuals from the cities. The Central Committee and the State Council built 106 May 7 cadres schools, scattered over eighteen provinces. Over 100,000 officials from the central government,including Deng Xiaoping, and 30,000 family members were sent there. Lower-level government offices set up tens of thousands more cadre schools, where an unknown number of middle- and lower-ranking cadres was sent for reeducation.

Advance courageously along the great glorious road of Chairman Mao’s ‘May 7 Directive’, 1971

The living conditions in these schools were usually quite bad. The cadres, used to a less strenuous life, had to do manual work, growing their own food. The aim of the schools was to become self-sufficient in food; usually, however, basic rations had to be brought in by the units to which the cadres belonged. Moreover, the goal of learning from the poor and lower-middle level peasants was no success either: many peasants living in areas where a cadre school was set up resented their arrival, and saw the cadres, who in their eyes did not amount to much in terms of labor power, as a threat to their own survival. Many cadres and intellectuals could not deal with the harsh life and died in the process of reeducation.

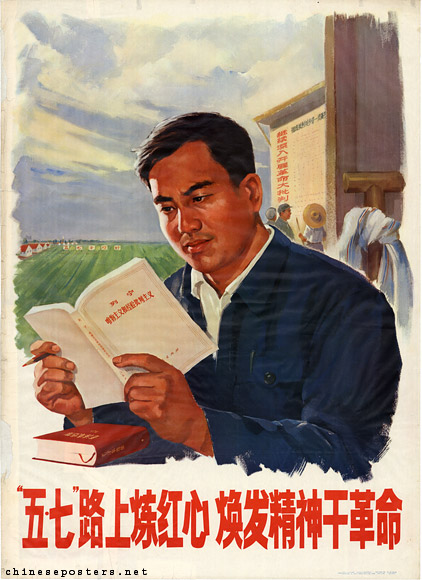

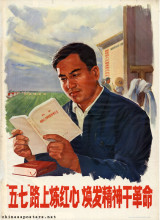

Walk the road of the May 7 Cadre Schools to persevere in continuing the revolution, 1976

Going up the mountains and down to the villages is glorious, 1974

After Lin Biao fell from power in 1971, the cadres and intellectuals, as well as their dependents, were allowed to return to the cities and resume their work. One by one, the May 7 cadre schools were closed down; they ceased to exist after the Cultural Revolution.

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Yang Jiang, A Cadre School Life - Six Chapters (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing Company, 1982)

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1995)

Li Zhensheng, Red-Color News Soldier - A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey through the Cultural Revolution (London: Phaidon Press, 2003)

Lu Xing, Rethoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution - The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture and Communication (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2004)

Michael Schoenhals (ed.), China’s Cultural Revolution, 1966-1969 - Not A Dinner Party (Armonk: M.E Sharpe, 1996)

Yang Kelin (ed.), Wenhua dageming bowuguan [Museum of the Cultural Revolution] (Hong Kong: Dongfang chubanshe youxian gongsi, Tiandi tushu youxian gongsi, 1995) [in Chinese]