Although its name may sound Chinese, the sport of table tennis (ping pong, Pīngpāng qiú, 乒乓球) did not originate in China; invented as an after-dinner diversion in late-19th century England, it made its way into China through the Western settlements via Japan and Korea only in 1901. Starting in the urban areas, it became popular elsewhere over the years.

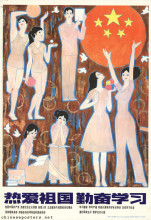

China has long been portrayed as "the sick man of Asia" and this image shaped Chinese attitudes towards sports, body and nationalism; it stood in dire need of being altered and refuted. In the public perception, the association between the fragile Chinese bodies and the humiliating past was often made. The photographs of imperial China that circulated both at home and abroad reinforced this perception, showing queued, effeminate, emaciated men with long fingernails and tired and expressionless faces in rundown, ramshackle surroundings. These images suggested that Chinese men lacked both the physical and emotional strength that the powerful imperialist Westerners exuded. Similarly, the long practices of binding women’s feet and relegating them to the inner household had obstructed the development of women’s strength and reflected negatively upon the nation. The weakness of the Chinese people thus was seen as one of the main causes of the crisis that beset the nation.

Taking their cue from the popular theory of Social Darwinism, reformers in the late Qing and Republican era saw the development of sports as a much-needed aspect of self-strengthening the nation as well as national pride. By 1911, modern, Western-inspired sports were no longer a phenomenon only seen in the treaty ports along the Eastern seaboard; they had become activities that were shared all over the Chinese territory. During the early years of the Republic, nationalism grew in importance to become the only thing that could save the nation from imperialism. Concurrently, debates were raised among Chinese intellectuals about military training and physical education in schools and the notion of a martial spirit became an essential educational principle. As a result, physical education and military training became overlapping physical activities in schools; they were to strengthen the nascent nation-state.

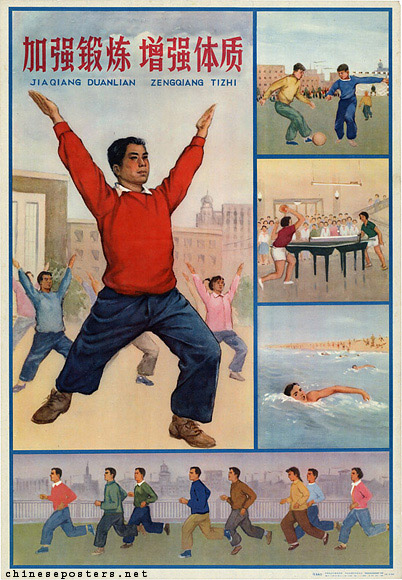

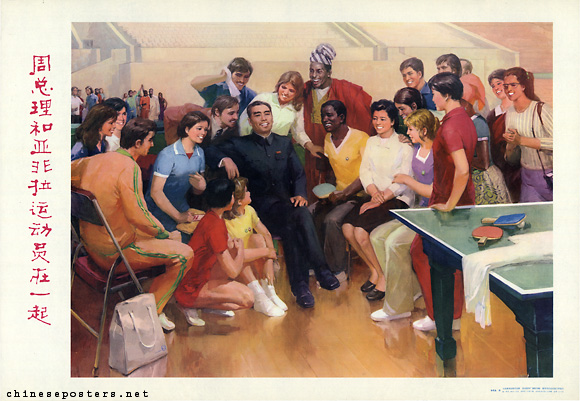

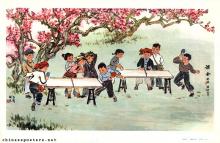

Strengthen training, enhance the physique, 1965

The movement was not without success: a renewed confidence in the people’s prowess can be read from the organization of the National Games, which started in 1910 and would continue until 1948. In international competitive perspective, Chinese athletes might not really have made the mark, yet, as the Chinese performances at the Far East Asian Games (1913-1934) indicated, but at least China was showing the world that Asia’s sick man was in the process of recuperating. As far as table tennis is concerned, Japan and the Philippines initially dominated the sports; only in the 8th edition of 1927, organized in Japan, was China able to take the medals. Once the Guomindang had succeeded in reestablishing some unified control over China in 1927, ‘training strong bodies for the nation’ continued to be of paramount concern, as can be seen from its inclusion in the Nanjing government’s New Life Movement (1934-1940). Table tennis was one of the sports played in the Jiangxi Soviet as well.

Soon after the founding of the PRC in 1949, probably around 1952, Mao Zedong made ping pong the new national sport (guoqiu, national ball). He chose ping pong because it seemed like a sport that China could afford: no big expensive courts were necessary and the equipment could, when necessary, be easily and cheaply improvised. Added to that, table tennis required minimal physical effort and could be played by virtually everyone, young and old. Moreover, with table tennis China would be able to compete against other countries, and thus to break out of its isolation and to present its new-found national strength on the international stage. In the 1930s, the (Republican) Chinese Table Tennis Association had failed to join the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF), thus, due to the absence of Taiwan and its potential supporters, enabling the PRC to join it in 1953.

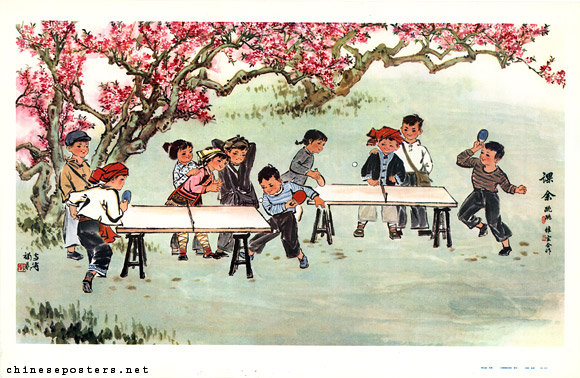

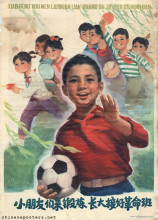

Female youngsters, go forth and play table tennis!, 1964

The opportunity to appear in the international arena gained added importance after 1958, when supra-national sports bodies such as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) started their boycott of the PRC in favor of membership of the Republic of China on Taiwan. On an ideological level, what also counted was that table tennis was not very popular in the world at the time; and especially important, the sport was not associated with elite participation as was the case with badminton, which had been considered before ping pong became the national pastime. The popularity of table tennis was further boosted by the fact that senior CCP leaders enjoyed playing it; Mao himself is known to have been an avid player. Moreover, ping pong was one of the ten sports that featured in the "Ten-Year Guidelines for Sports Development", promulgated by the State General Sports Administration in 1958.

China’s decision to embrace table tennis paid off well: the women’s team ranked high in 1956-1957, and in 1959, Rong Guotan made history as the first Chinese sportsman to win a world championship. From 1961-1965, Chinese domination continued, as shown by Zhuang Zedong who brought home the championship three times in a row.

But even successful sports like table tennis were subject to conflicting demands: on the one hand, they had to serve as an informal leisure activity, as practiced by the masses. But on the other, they were to "strengthen male and female bodies" and serve as "the performance of national strength". This was clearly the domain of organized sports organizations, training facilities and elite athletes, strongly supported by the state, imbued with and structured by extraneous goals and expectations. The conflict between mass activity and elite sport came to a head in 1968 after the Cultural Revolution had started. The Ministry of Sports under Marshal He Long and the sports commissions on every provincial and county level were disbanded, their responsibilities taken over by the military. Influential sports officials such as He Long and Rong Gaotang were accused of taking the capitalist road, neglecting the interest and health of the people, only concentrating on a small elite and on medals; the latter in particular was termed "cups and medals mania".

In the process, the training system was dismantled, sports schools were closed, sports competitions ceased, and Chinese teams stopped touring abroad. The table tennis team that had won 15 medals at the 1965 World Championships missed the 1967 and 1969 Championships. Provincial and local teams were broken up. Coaches and athletes were sent to the countryside and factories to do physical labor.

Apart from table tennis, gymnastics and athletics teams, most national teams were disbanded. Outstanding athletes were condemned as sons and daughters of the bourgeoisie, their coaches were denounced and prosecuted. Three internationally acclaimed table tennis players, Fu Qifang, Jiang Yongning and Rong Guotang, originally from Hong Kong, were accused of being spies and beaten up, eventually leading to their suicides in 1969.

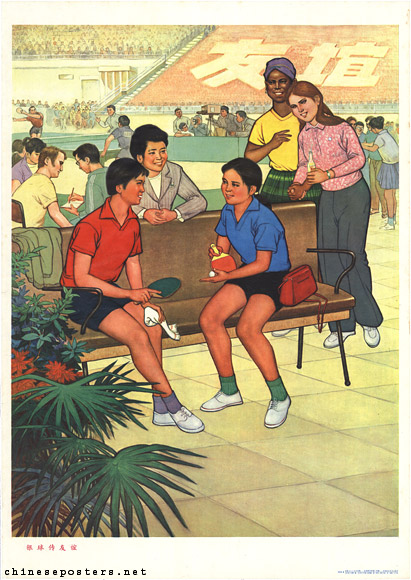

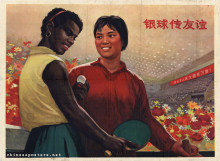

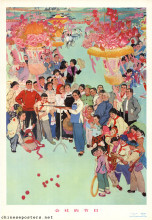

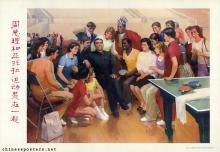

Table tennis spreads friendship, 1972

Once the internal situation seemed to have somewhat normalized after 1969 and the CCP leadership had the breathing space to reassess the global strategic situation and the potential external threats to China, it was decided to try and normalize relations with the United States. One of the attempts to signal this to the American side was to invite Edgar Snow, the American journalist and author of Red Star over China (1938), to attend the 1 October Parade in 1970. The highly symbolic image of Snow standing next to Mao on the rostrum of Tian’anmen failed to draw the attention of the American side.

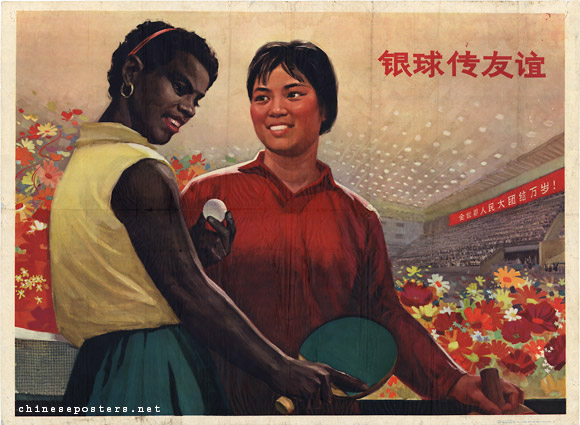

The silver ball conveys friendship, 1973

The second occasion that presented itself was the 31st World Table Tennis Championships in Nagoya, Japan, between 25 January and 3 February 1971. China had returned to playing international level table tennis at the Scandinavian Open Championship in Sweden in November 1970, marking the first time that Chinese teams faced international competition since the Cultural Revolution had started. China had been specifically invited to attend the Nagoya meet by the organizer, the Japanese Table Tennis Association. While the PLA-dominated sports-bureaucracy hemmed and hawed, Mao signaled his approval, personally setting out the principles of participation for the Chinese team: friendship first, competition second. The Chinese team went and acted on the following instructions: "If you meet the U.S. team do not initiate communication, but do not refuse to communicate. If you compete with the U.S. team, do not exchange flags, but shake hands instead." During the meeting, the American and Chinese players became friends. After the Americans found out that the Chinese had invited Britain, Australia, Canada, Colombia and Nigeria to visit China after the Championships, the Chairman of the American Table Tennis Association asked whether they could visit China too. Mao agreed and within days, the era of ‘Ping-Pong diplomacy’ had started. On 14 April 1971 the US players were received by Zhou Enlai at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. The table tennis match was held in the Capital Gymnasium (or Capital Indoor Stadium), watched by an audience of 18.000 Chinese.

This time, the hint was understood by the American government; within a matter of days, changes in US policy towards the PRC were announced, including the lifting of the trade embargo that had been in place for 21 years and a cessation of the opposition to the PRC’s attempts to regain China’s seat in the United Nations and the Security Council. After that, both sides moved quickly to establish a rapprochement, culminating in Richard M. Nixon’s historical visit to China in February 1972.

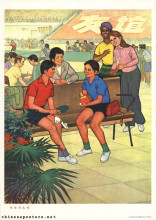

Premier Zhou with athletes from Asia, Africa and Latin America, 1979

’Ping pong diplomacy’ was not only a means to effect a normalization of relations with the US. As strong proof of the PRC’s understanding of the use of sports as "soft power", other countries were courted by table tennis in a similar way. The resumption of diplomatic relations with Japan in 1971 can be seen as resulting from China’s participation at Nagoya. In the mid-1970s, China re-established formal ties with India, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia as a result of table tennis meets.

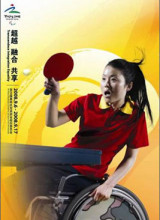

The international dimensions of playing ping pong strengthened its popularity in China. When the Mass Sports Movement was inaugurated in 1972, table tennis was one of the activities included. Due to its broad player base and intensive training systems, China increasingly succeeded in dominating global table tennis. This situation did not change once China opened up to the world after 1977; indeed, with more opportunities to compete globally, more tournaments could be won. The Chinese chain of victories lengthened even further once the country (re)joined international sports associations such as the IOC (1979) and once more started taking part in global events such as the Olympic Games.

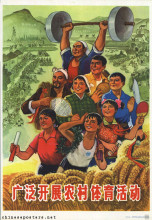

Make a good start to train the body, participate in out-of-school activities, 1982

At the same time, table tennis, while still considered one of the Chinese ‘stronghold events’, has started to lose some of its pre-eminence and popularity. Soccer (football) has emerged as an even more broadly played mass sport, while basketball has gained more and more fans among the increasingly more globalized younger generations of players and spectators. As a physical activity denoting typical "Chineseness", ping pong has been replaced on a global scale by martial arts. Sports as a function of nationalism, as part of nation building, of identity formation, has made way for sports as a global business enterprise, in China as well as elsewhere.

Smash All Old Things! SIGHTINGS NO.3: PING PONG DIPLOMACY (23 June 2012) (http://smashalloldthings.blogspot.nl/2012/06/sightings-no3-ping-pong-diplomacy.html)

Fan Hong, "Not all bad! Communism, society and sport in the great proletarian cultural revolution: a revisionist perspective", The International Journal of the History of Sport 16:3 (1999)

Fan Hong, Ping Wu & Huan Xiong, "Beijing Ambitions: An Analysis of the Chinese Elite Sports System and its Olympic Strategy for the 2008 Olympic Games", The International Journal of the History of Sport 22:4 (2005)

Dong-Jhy Hwang, Sport, Imperialism and Postcolonialism: A Critical Analysis of Sport in China 1860-1993, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Sterling, 2002

Tony Hwang & Grant Jarvie, "Sport, Nationalism and the Early Chinese Republic 1912–1927", The Sports Historian, 21:2 (2001)

Lu Zhouxiang, "Sport, Nationalism and the Building of the Modern Chinese Nation State (1912–49)", The International Journal of the History of Sport, 28:7 (2011)

Andrei S. Markovits, "The Global and the Local in Our Contemporary Sports Cultures". Society 47 (2010)

Andrew Morris, "’To Make the Four Hundred Million Move’: The Late Qing Dynasty Origins of Modern Chinese Sport and Physical Culture", Comparative Studies in Society and History 42:4 (2000)

Nils Viktor Olsson, Ping-Pong Politics - How Table Tennis Became The National Sport of The PRC and Its Role in Modern Chinese Politics, (2010) (http://www.ittf.com/museum/ping%20pong%20politics.pdf)

Shaoguang Wang, "The politics of private time: changing leisure patterns in urban China", Davis, Kraus, Naughton, Perry (eds), Urban spaces in contemporary China – The potential for autonomy and community in post-Mao China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995)