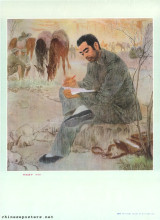

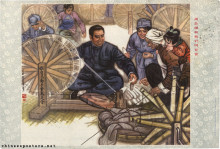

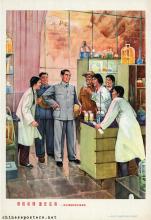

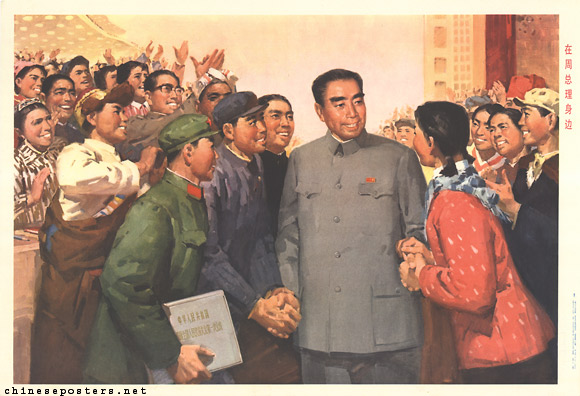

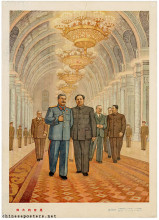

At the side of Premier Zhou, 1977

If Mao Zedong is considered as the founding emperor of the Communist dynasty, the suave and urbane Zhou Enlai (周恩来, 1898-1976) played the role of the loyal prime minister to perfection. As such, he is remembered more fondly by the people than any other leader of the so-called first generation. Zhou was born into an upper class family, but played a leading role in the student movement from a very early age on. His active participation in student demonstrations during the May 4th Movement (1919) led to his arrest and imprisonment. After his release, he joined a group of young intellectuals who went to France as worker-students. There he met countrymen who would play a defining role in the Communist Party, such as Deng Xiaoping and Zhu De.

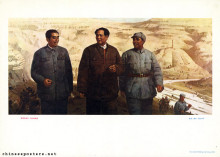

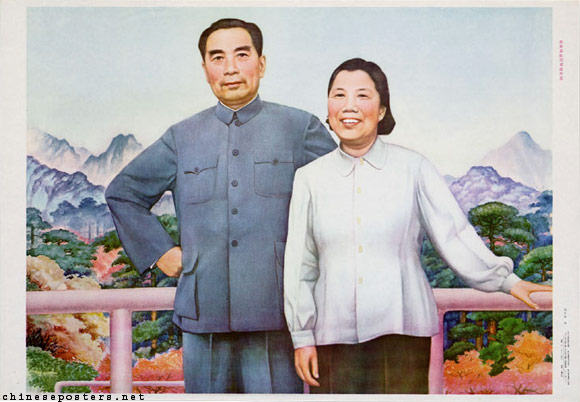

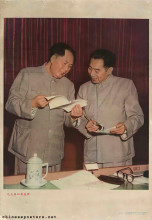

Comrades Zhou Enlai and Deng Yingchao, 1983

While in Europe, Zhou was active in setting up various branches of the CCP, which he joined in 1922. Upon his return to China in 1924, he became the director of the Political Department of the Whampoa Military Academy headed by Chiang Kai-shek. In 1925, he married Deng Yingchao in Tianjin. The couple remained childless, but adopted many orphaned children of "revolutionary martyrs"; one of the more famous ones was former Premier Li Peng.

During the Northern Expedition (of the New Revolutionary Army under Chiang Kai-shek which set out to liberate China from the various feuding warlords), Zhou was actively organizing workers' armed uprisings in Shanghai to prepare the ground for the take-over of the city. When the Guomindang, led by Chiang, turned against the CCP while marching into Shanghai in 1927, Zhou barely managed to escape the carnage which decimated the Communist ranks. Via Hong Kong and Moscow he rejoined Mao and the others in Jinggangshan. He participated in the Long March (1934-1935), and after the CCP set up its headquarters in Yan'an, Zhou became more or less responsible for the Party's external contacts. As such, he was the main negotiator with the Guomindang government during the various attempts to reach some form of cooperative agreement.

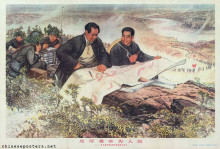

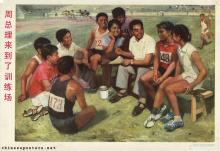

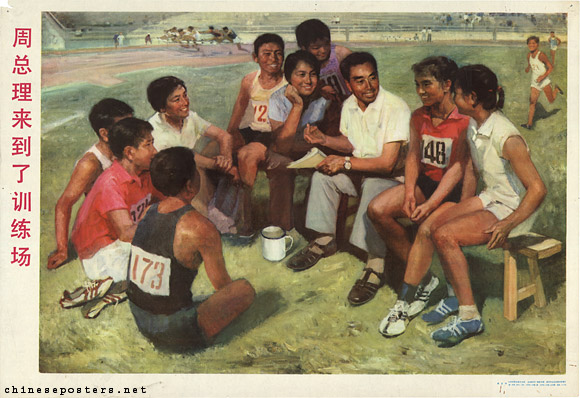

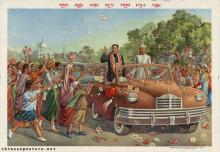

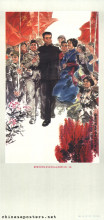

Premier Zhou has come to the training field, 1978

After the founding of the PRC in 1949, Zhou became Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs. In the latter capacity, he traveled widely to the growing number of countries in the Asia and Africa which recognized the new state. In 1955, during the first Conference of Non-Aligned Nations in Bandung (Indonesia), Zhou scored a great victory by having his "Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence" acknowledged as the basis for cooperation for Third World countries. Bandung implied that China was not merely a member of the communist block, but a Third World Country itself; the "Principles" moreover established China's credentials and earned the country much goodwill.

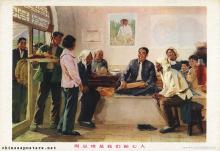

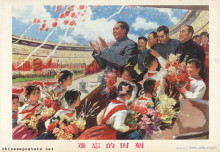

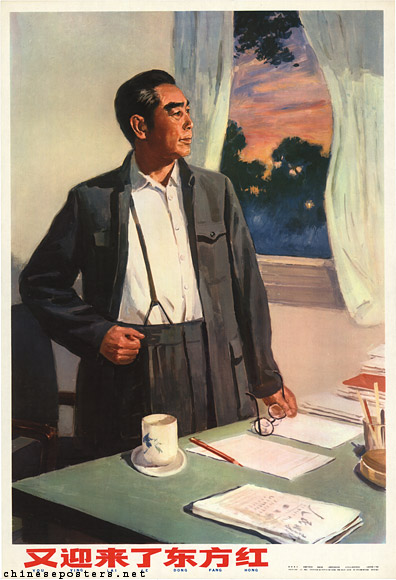

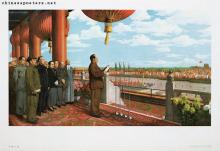

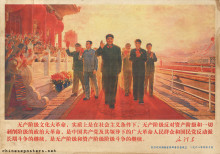

Once more welcoming the reddening of the East, 1978

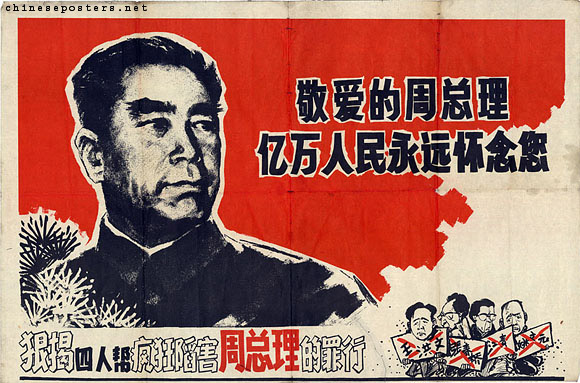

Zhou was not merely active on the international front. As Mao's policies become more and more radical in the 1950s (Great Leap Forward) and 1960s (Cultural Revolution), Zhou increasingly tried to maintain some semblance of normalcy in China, all the while remaining loyal to his superior. This earned him great sympathy from the population and great resentment from those who considered him an obstacle in their bids for power. During the Cultural Revolution, the "Campaign to Criticize Lin Biao and Confucius" (1974) that was inspired and organized by Jiang Qing and the Gang of Four, was in reality directed against Zhou. After all, Zhou had done his best to try and save many old comrades, cadres and colleagues from persecution. Moreover, he had been instrumental in the process of normalizing relations with the United States; this culminated in the famous 1972 visit of Richard Nixon to the PRC.

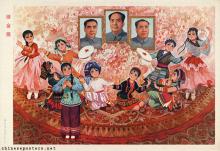

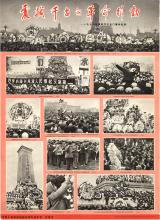

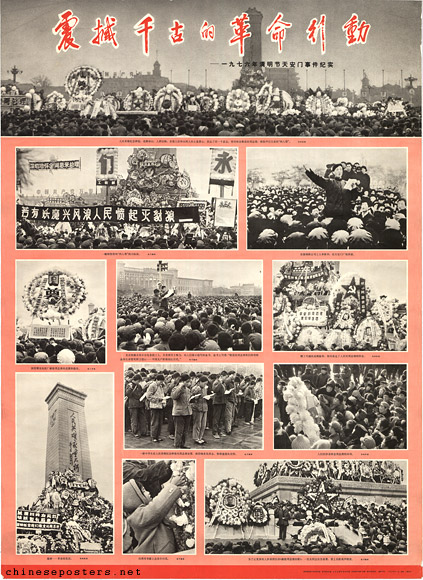

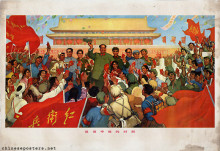

A revolutionary movement that vibrates through the ages, 1978

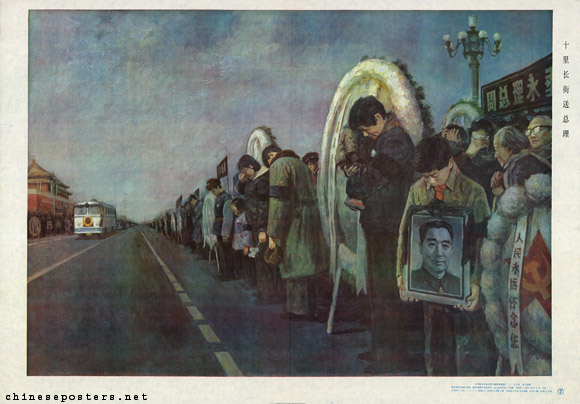

When Zhou Enlai died from cancer (and exhaustion) in January 1976 and the people were not given the opportunity to publicly mourn "the beloved Premier", the popular resentment this created led to the "first Tiananmen Incident" of April 1976.

The 10-mile long road says farewell to the premier, 1988

While alive, Zhou never became the object of a personality cult; as the perfect Premier, he had to remain in the shadow of Mao. Only after his death, and after the end of the Cultural Revolution, Zhou became a regular subject on posters. This had much to do with the claims to legitimacy of both Hua Guofeng and Deng Xiaoping. Deng in particular styled himself very much as the successor of Zhou. The "Four Modernizations", the plan to modernize and reform China, which Deng was able to have adopted in December 1978, for example, was directly attributed to Zhou.

As proof of his everlasting contribution to the Chinese revolution, one of the four memorial rooms that were added in December 1983 to the Memorial Hall where Mao's remains were on display was dedicated to Zhou.

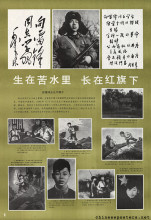

In 1998, the centenary of Zhou's birth was celebrated with the release of a number of posters featuring him. The China Art Gallery in Peking mounted a photo exhibition which contained many interesting images of Zhou meeting with various deceased leaders.

David Apter & Tony Saich, Revolutionary Discourse in Mao’s Republic (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1994)

Gao Wenqian, Zhou Enlai - The Last Perfect Revolutionary (New York: PublicAffairs, 2008)

Dachang Cong, When Heroes Pass Away - The Invention of a Chinese Communist Pantheon (Lanham MD, etc.: University Press of America, 1997)

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham, etc.: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao - The Memoirs of Mao’s Personal Physician (London, etc.: Random House, 1996)

Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Volume III: The Coming of the Cataclysm (Columbia University Press 1999)

Rudolf G. Wagner, "Reading the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Peking: The Tribulations of the Implied Pilgrim", Susan Naquin & Chün-fang Yü (eds), Pilgrims and Sacred Sites in China (Berkeley, etc.: University of California Press, 1992)

Yan Jiaqi & Gao Gao (translated & edited by D.W.Y. Kwok), Turbulent Decade - A History of the Cultural Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1996)

David Zweig, "A Photo Essay of a Failed Reform -- Beida, Tiananmen Square and the Defeat of Deng Xiaoping in 1975-76", China Perspectives [Online], 2016/1 (http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/6893); DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.6893

![[Zhou Enlai]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/e17-114.jpg?itok=e0BUvosm)