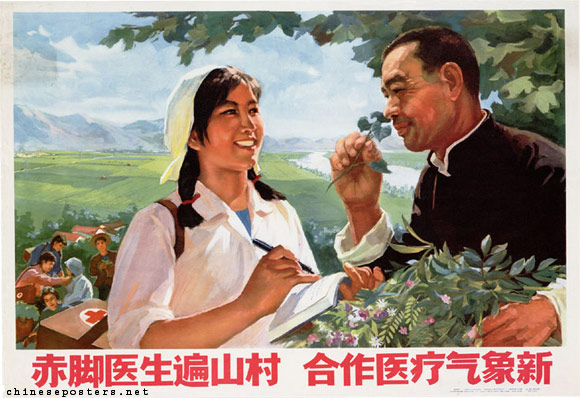

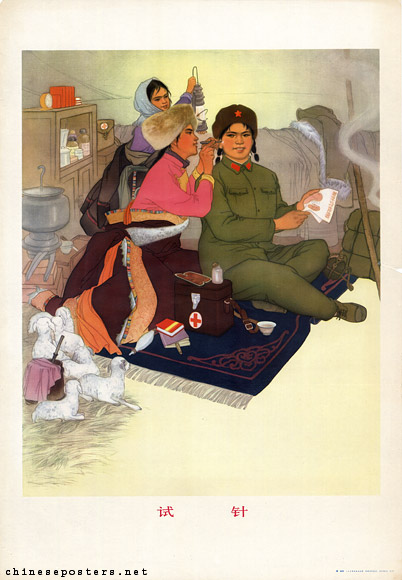

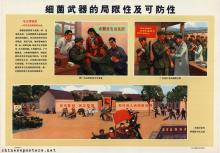

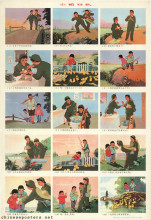

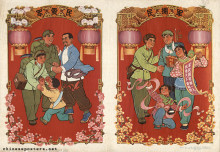

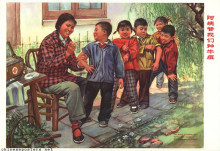

When the rural communes were set up during the Great Leap Forward (1958), health care was organized in health stations at the commune level. The people employed by these stations were part-peasant, part-doctor. As they wore no shoes most of the time, they became known as barefoot doctors (赤脚医生, chijiao yisheng), a title that was made official in 1968.

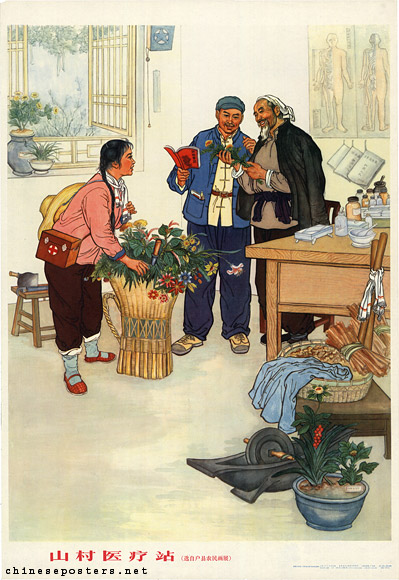

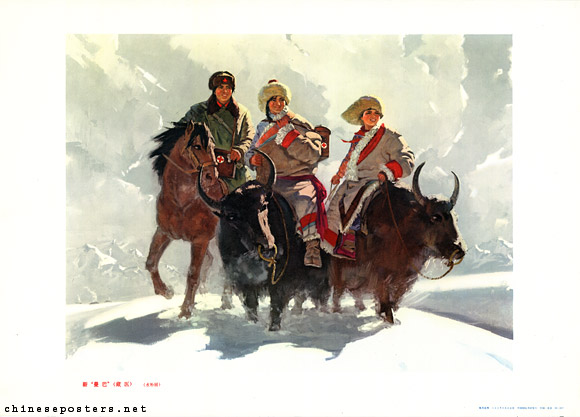

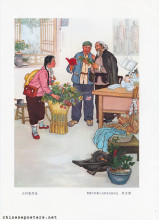

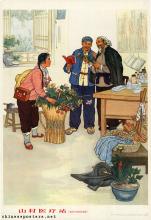

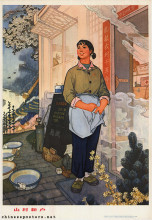

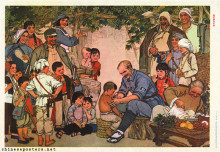

Mountain village medical station, 1975

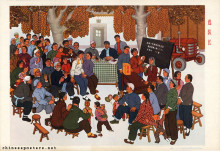

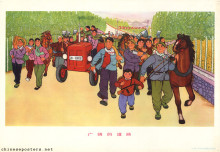

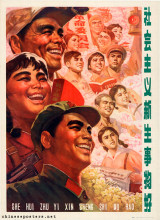

In 1965, Mao Zedong stressed the importance of improving the state of health and hygiene in the countryside. He argued that the urbanites, who constituted only 15% of the population, were the main beneficiaries of the existing system of health care, whereas the large peasant population had no access to medical services or medicine. To reverse this situation, it was decided that one-third of the medical workers and administrators from the cities should start working in the rural areas to improve hygiene.

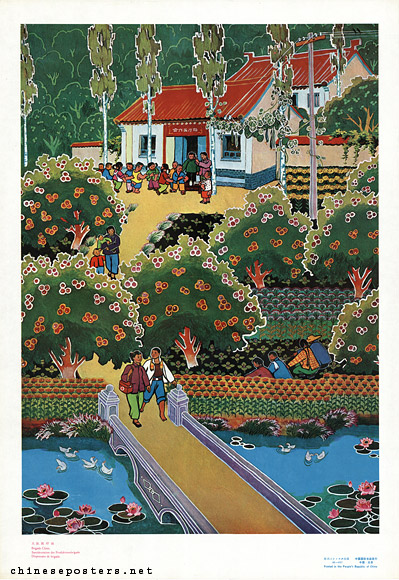

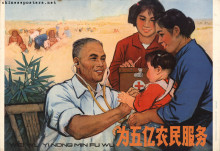

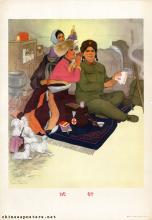

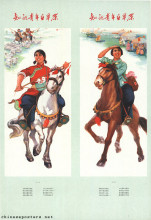

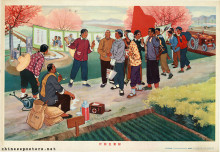

A new doctor in the fishing harbor, 1975

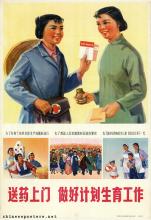

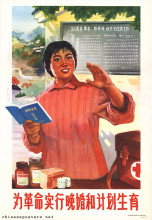

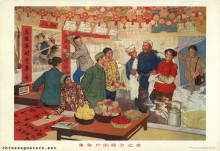

As a result, large numbers of sub-standard medical staff or health professionals with political problems were despatched to the countryside. As barefoot doctors, they were to "promote and implement state hygiene principles and policies; administer the water works and sewage systems; make improvements in wells, toilets, livestock areas, stoves and environment; give vaccinations; control infectuous diseases; collect information on epidemics; and provide simple medical treatment and temporary rescue." In the early 1970s, barefoot doctors were also given an active role in the implementation of the family planning policy then in force.

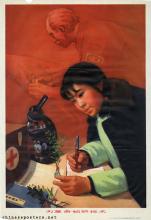

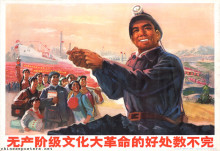

During the Cultural Revolution, many medical experts with an unreliable political background were sent to the countryside. Although barefoot doctors were lauded as one of the "new things" that the Cultural Revolution had created, the medical field, research and education were weakened as a result. The cities were deprived of doctors, while semi-skilled barefoot doctors were active in the rural areas. In 1985, the term "barefoot doctor" ceased to be used. Those with the qualifications of practitioner were henceforth called "rural doctors", while those lacking these qualifications were to use the title of "health worker."

Abigail Holst, Chinese Propaganda Posters in Mao’s Patriotic Health Movements: From Four Pests to SARS (BA Thesis, Emory University, Atlanta, 2016)

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Lan Angela Li, "The edge of expertise: Representing barefoot doctors in Cultural Revolution China", Endeavour 39:3-4 (2015), 160-167

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press 1995)

Christos Lynteris, The Spirit of Selflessness in Maoist China -- Socialist Medicine and the New Man (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013)