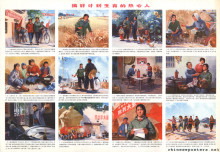

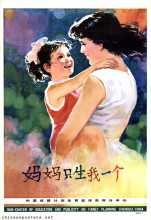

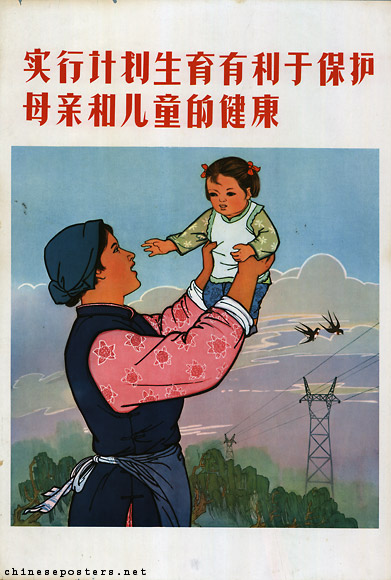

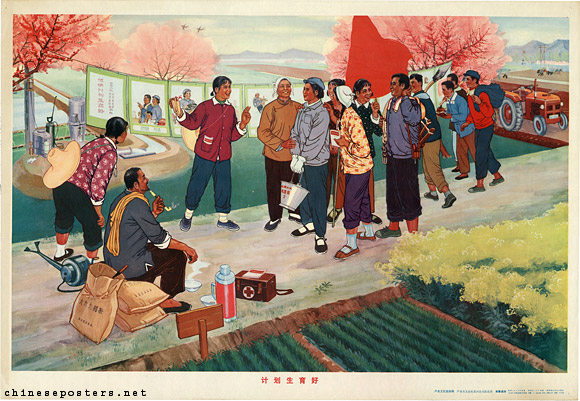

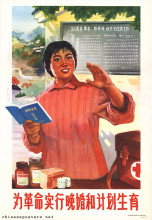

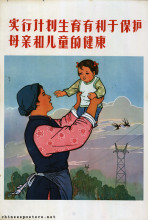

Practicing birth control is beneficial for the protection of the health of mother and child, 1975

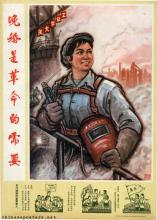

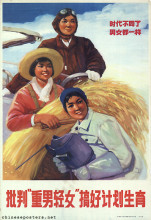

Various types of campaigns to manage the size of the population started as early as the mid-1950s. Generally speaking, they were targeted at women. The early campaigns concentrated on family planning rather than on population reduction, but it was obvious that all aspects of birth control were considered to be a female responsibility. This impression was strengthened further by the fact that the person in charge of the implementation of the policy was the (local) representative of the Women’s Federation - usually a woman. In the period of mass upheaval that marked the Great Leap Forward, there was no time and no political inclination to address population issues.

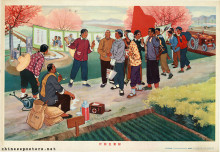

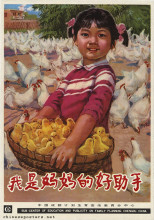

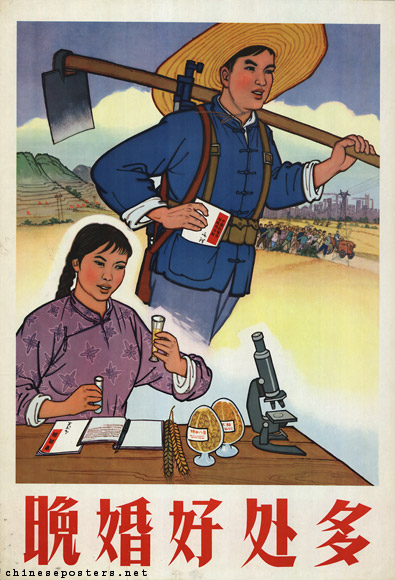

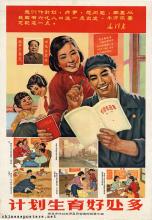

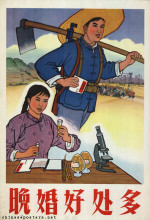

Marrying late has many advantages, 1975

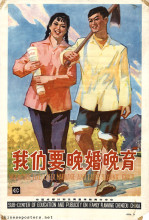

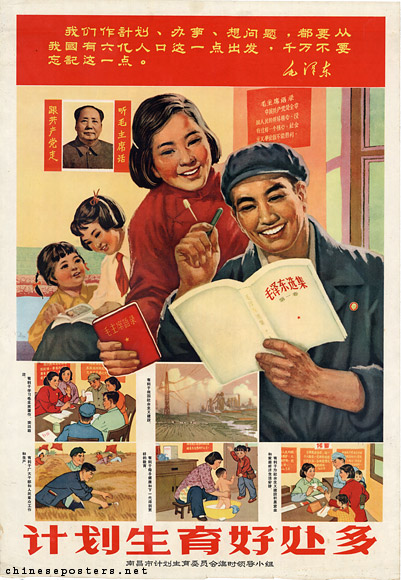

As early as 1956, the term "planned childbirth" (jihua shengyu 计划生育) began to buzz around the various departments that were caught up in the planning campaign resulting from the relative successes of the First Five-Year Plan. While most leaders continued to advocate birth control rather than birth planning, the latter increasingly became the guiding doctrine. Even Mao supported this development, endorsing the need for birth planning in public at various occasions in 1956-1957.

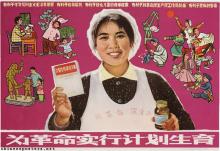

Practice birth control for the revolution, 1974

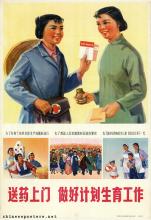

Contraceptives became widely available only in 1962, coinciding with the reaffirmation of the need for birth planning work. It was seen as key component of the economic recovery strategy following the grain and food crisis of the failed Great Leap. Even during the Cultural Revolution, and in particular after 1969, steady progress was made with setting up an administrative framework for planning policies. Yet, family planning remained voluntary until 1970. In that year, and again with Mao’s explicit blessing, a beginning was made with a sustained attempt to implement family planning as part of a policy to reduce the birth rate to 2%.

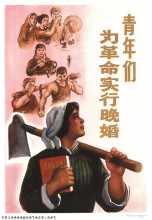

Marry late for the revolution, no date

To bring this about, a new model of family size was propagated, accompanied by such slogans as "later, spaced and few", and "one’s not too few, two will do, and three are too many for you", limiting each couple to two children. Zhou Enlai was the proponent behind this plan, which was unevenly enforced.

In contrast with the first two decades following 1949, when family planning had been voluntary and the final decision to adopt birth control methods had been left to the couples themselves, some attempts now were made to implement the policy according to a quota system.

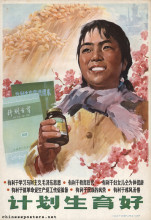

Practice birth control for the revolution, 1972

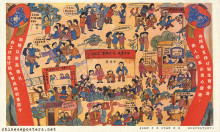

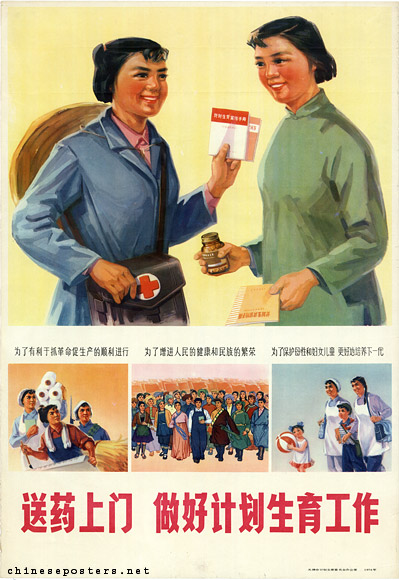

To publicize this campaign, a nation-wide network was set up to provide family planning services, in the form of committees for planned birth work, which were organized at every administrative level. The cadres working here - often, but not always women - were made responsible for family planning education. The delivery of contraceptives was closely tied in with the provision of basic health care by local clinics in urban areas and by the barefoot doctors in the countryside. Other means of birth control (IUD, abortion, sterilization) were provided free of charge.

Deliver medicine (contraceptives) to the doorstep, do a good job in birth control work, 1974

The medical means of birth control were supplemented with the personal approach and peer group pressure in the small group (xiaozu 小组). In factories, enterprises, urban streets and rural villages, women were divided into small groups headed by a family planning worker, who organized the meetings and met with each member individually. Birth quotas were passed downwards through the administrative hierarchy until each small group received its allocated number of births. Thus, decisions regarding family size became subjected to intervention by the state in the form of controlled peer or group pressure.

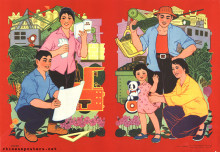

Family planning has many advantages, 1974

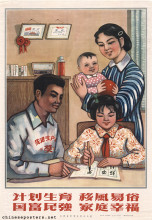

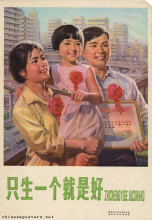

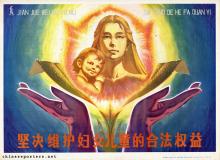

Carry out family planning, implement the basic national policy, 1986

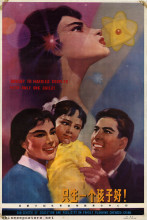

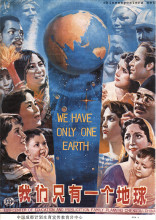

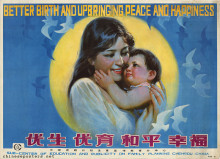

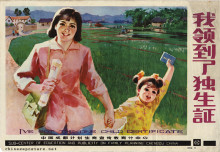

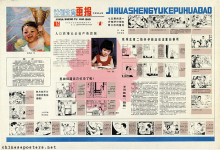

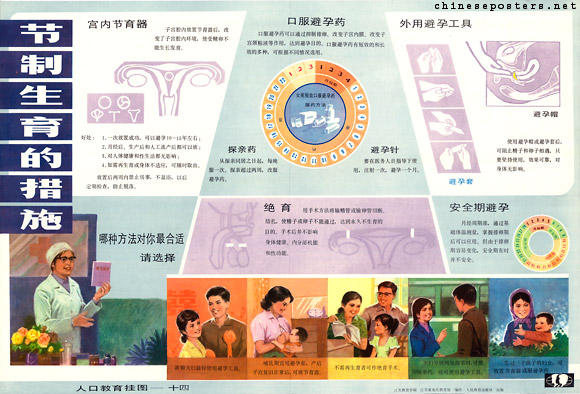

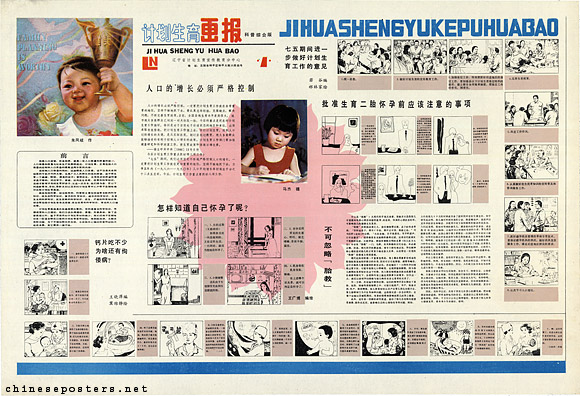

Propaganda posters were widely employed in the 'one child'-campaign, which started in 1979 in an attempt to deal with the staggering increase of the population in the 1960s and 1970s and to curb the projected problematic growth in the future. This campaign went much further than the "late, spaced and few"-campaign that had been started in the early 1970s. Reflecting the traditional educational purposes of the posters, special materials were produced that paid attention to aspects of reproduction, sexuality and conception. The responsible departments for these educational materials could range from ministries to local population policy centers.

Birth control measures, Population education wall charts, late 1980s

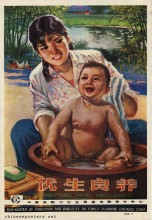

'Posters popularizing the science of family planning' explained the mechanism of human reproduction, and the various available methods to limit one's offspring to a single child. They were produced for use in glass display cases erected in streets or for community rooms. Such educational posters included explanations about what a woman feels when she is pregnant, the use of condoms, etc. It should be no surprise that such posters in many cases contributed in a major way to an increase of the general sexual knowledge of many people, something that often was lacking.

Posters popularizing the science of family planning, 1987

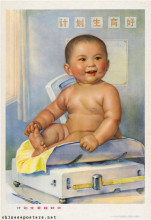

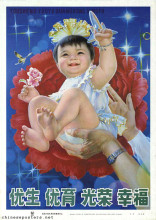

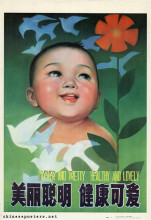

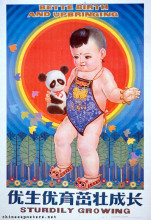

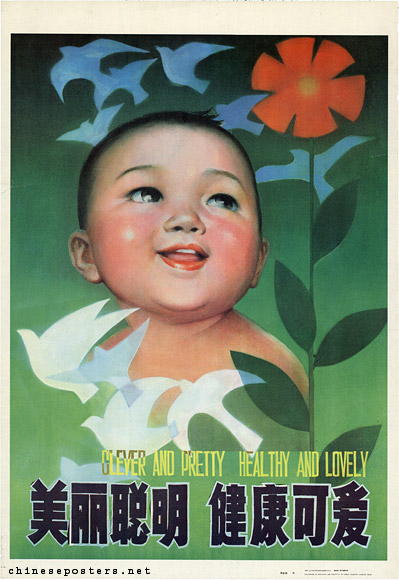

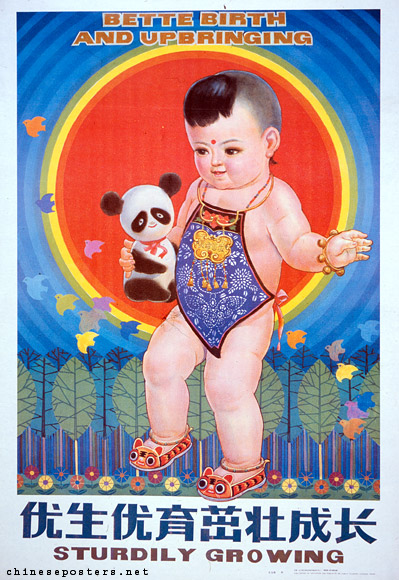

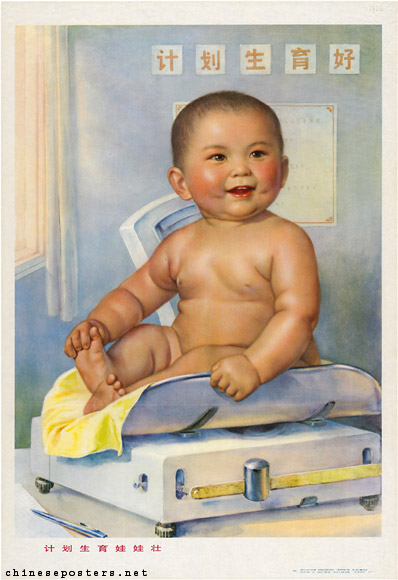

In order to communicate the message that the offspring of a couple from now on should be limited to one child, traditional visual elements from nianhua (New Year prints) were used that were known to appeal to the people. The pictures featuring chubby baby boys and gold carp attracted the population of both rural and urban areas, whether or not they contained slogans to the effect that 'one is better.'

Clever and pretty, healthy and lovely, 1986

Bette(r) birth and upbringing, sturdily growing, 1986

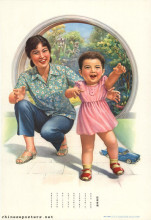

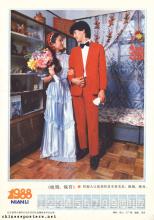

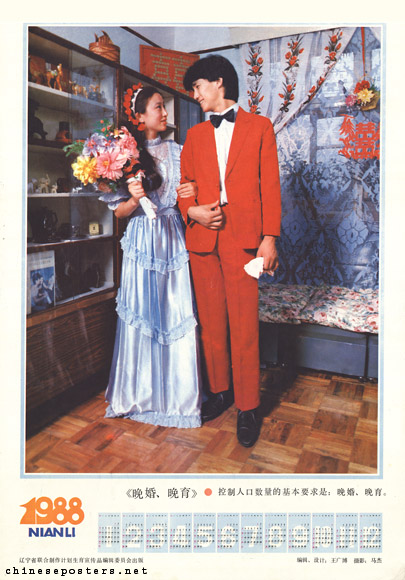

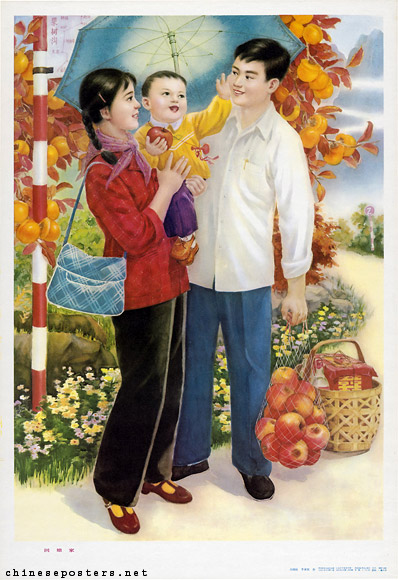

In other posters, young people still were called upon to marry later, to conceive later and have less children, as illustrated by the two posters below, which includes a calendar for 1988. Such urgings echoed the population policies espoused in the early 1970s.

Marry late, conceive late, 1988 calendar

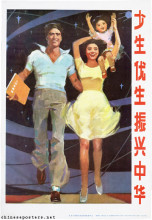

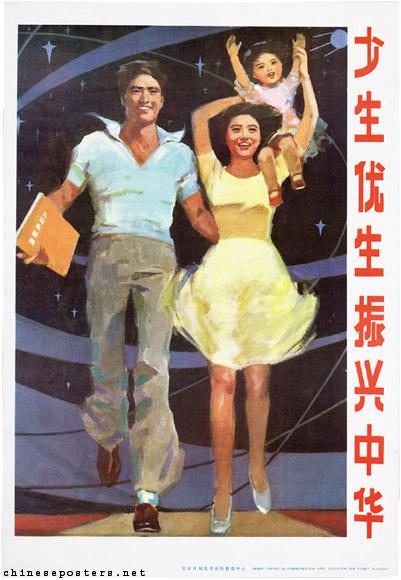

Less births, better births, to develop China vigorously, 1987

Western bridal clothes were not the only indication that the people's livelihood was improving. Various elements of economic development started to creep into the more traditional poster-design. This started with highrise buildings in the background, and ended with the use of Western imagery: space ships, atomic symbols, even remote controls. The visual element that many of these posters have in common is the dove; this bird is not presented as the traditional emblem of long life, but as the internationally accepted icon of peace.

Do a Good Job in Family Planning to Promote Economic Development, 1986

As the campaign progressed, the aim of having fewer children was equated with an increase in the national development of wealth for all. The single child would contribute to the national policy of modernization and reform. With fewer children to take care of, the 'inherent quality' of those children that were born would improve. By the mid-1980s, the urgings to limit the number of children increasingly were grounded in authoritative scientific justifications that stressed that in this way, the gene pool could be improved. These arguments were given a legal character in the mid-1990s with the introduction of legislation to promote eugenics. A recurring argument was that parents could concentrate on their single child and devote more time to their upbringing.

Eugenics cause happiness, 1987

What really leaps out from these posters is their urban bias, and this should give food for thought about the effectiveness of the 'One Child'-campaign as a whole. In general, urban couples were more amenable to the goals of the campaign than their rural counterparts and abided more easily to the stipulations. City dwellers were confronted almost on a daily basis with the crippling effects the huge population had on the local infrastructure and the availability of housing. The control network of the population representative of the urban neighborhood committees also was much more comprehensive than that of her rural counterpart. These considerations all contributed to the fact that the policy on the whole was more successful in the cities. In the countryside, on the other hand, the population pressure was felt much less. Population representatives had fewer opportunities to keep track of births. As a result of the rural reforms, having many children was seen as a sure way to earn more income. In fact, many peasants considered the fines that had to be paid when more children were born as a small investment that the children would repay manifold in the future. Moreover, having as many children as possible still was seen as the only way to ensure that the parents would be looked after in their old age. And lastly, the lingering influence of ancestor worship made it imperative that at least one child would be male. In short, the lack of propaganda posters explicitly addressing the 'One Child'-policy in rural terms has been simply astonishing.

Children born under planned parenthood are strong, 1978

Returning to a married woman's parents' home, 1983

On 29 October 2015, the CCP leadership announced that all couples, urban or rural, were allowed to have two children. This announcement marked the official end of the 'One Child'-policy and the beginning of a new, two-child policy.

Elisabeth Croll, Delia Davin, Penny Kane (eds), China’s One-Child Policy (London: MacMillan, 1985)

Francine M. Deutsch, "Filial Piety, Patrilineality, and China’s One-Child Policy", Journal of Family Issues 27:3 (2006), 366-389

Vanessa L. Fong, Only Hope - Coming of Age under China’s One-Child Policy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004)

Susan Greenhalgh, "Missile Science, Population Science: The Origins of China’s One-Child Policy", The China Quarterly (2005), 253-276

Susan Greenhalgh, "The Biopolitics of the Three-Child Policy", Made in China Journal, 6 June 2024

Fuqin Liu, Jiaming Bao, Doris Boutain, Marcia Straughn, Olusola Adeniran, Heather DeGrande & Stevan Harrell, "Online responses to the ending of the one-child policy in China: implications for preconception care", Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences (2016)

Thomas Scharping, "Hide-and-seek -- China’s elusive population data", China Economic Review 12 (2001), 323-332

Yaojiang Shi & John James Kennedy, "Delayed Registration and Identifying the 'Missing Girls' in China", The China Quarterly (2016), 1-21

Tyrene White, China’s Longest Campaign - Birth Planning in the People’s Republic, 1949-2005 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006)

![The great significance of implementing [the policy of] marrying late and birth control](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/e15-180.jpg?itok=cd_PADVQ)

![Realize [the policy of] marrying late and birth control to liberate the labor power of women](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/e15-205.jpg?itok=myEEEe_3)