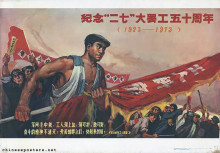

The February Seventh Movement, 1963

In its early years, the Communist Party gave priority to organizing workers in the more urbanized regions. Along the 1,200 km. long Beijing–Hankou railway (京汉铁路), more than a dozen trade unions were formed. A meeting to establish the Beijing-Hankou Railway Federation of Trade Unions (京漢鐵路總工會), merging these local unions, was planned for February 1, 1923, in Zhengzhou (郑州), about halfway between Beijing and Hankou. This meeting was obstructed by warlord Wu Peifu (吳佩孚). In response, the unions called a general strike, starting February 4. Some 20,000 railway employees layed down their work.

Warlord Wu Peifu reacted with ruthless violence. His military police besieged the union's headquarters in Hankou (now part of Wuhan), and killed 40 strikers on February 7. This event became known as the February Seven massacre (二七慘案). Large numbers of railway workers were fired during the next weeks.

After the defeat, the Communist Party reconsidered its strategy that relied heavily on a revolutionary workers' class, and started looking for more cooperation with Sun Yat-sen's Guomindang.

Commemorate the 50th anniversary of the great strike of February Seventh, 1973

Jared Hall, China’s First Red Martyrs: The February Seventh Massacre of 1923 and the Politics of Historical Memory (thesis, George Washington University, Washington DC, 2010)

Luo Zhanglong, 1923. The 7 February Massacre, in: Ivan Franceschini, Christian Sorace (eds.), Proletarian China: A Century of Chinese Labour (London: Verso Books, 2022), 74-86

Tony Saich, "Background to the 7 February Peking–Hankou Railway Workers' Strike", Chinese Sociology and Anthropology: A Journal of Translations 25 (1992-1993), no. 2, 1–18