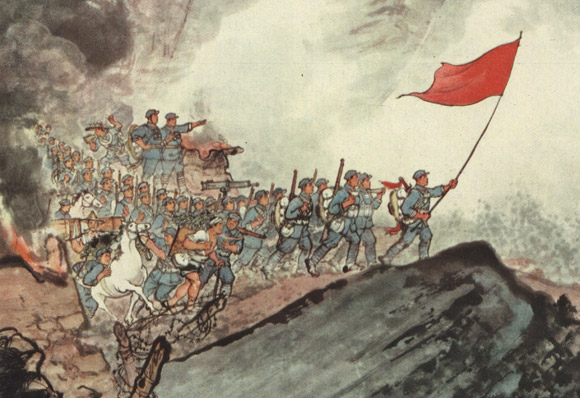

The start of the Long March. Detail from An arduous journey scroll (one). Ruijin, 1961

The Long March (长征, Changzheng) started when Communist forces, surrounded by the Nationalist army, had to flee their base in Jiangxi province, October 1934. After a journey of some 10.000 kilometer (6.000 miles), which took a year, they arrived in Northern Shaanxi. In between, hard battles were fought, and fast flowing rivers, snowy mountains and treacherous marshes crossed. The March started with 80.000 people, a mere 8.000 arrived in Shaanxi. And during all this, a struggle for power within the Party was fought with a vengeance.

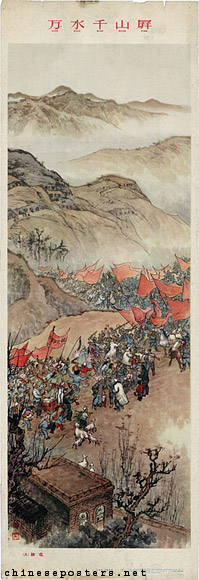

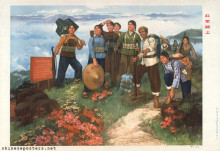

An arduous journey scroll (one). Ruijin, 1961

At the start of what would become the Long March, the Communist Party was led by Bo Gu (博古, 1907-1946), who had studied in Moscow and mostly followed the Soviet Union’s guidelines, aided by Comintern advisor Otto Braun. After some heavy defeats, Mao challenged their strategies and was able to get enough support from other Party leaders, including Zhou Enlai who had initially supported the "Bolshevik" faction. From then on, the Chinese Communists would focus on gaining support from the peasant population, and on avoiding direct military confrontations. Instead, guerrilla warfare would be waged, and a power base built from which larger battles could be won eventually. At the same time, Mao secured his position as absolute leader.

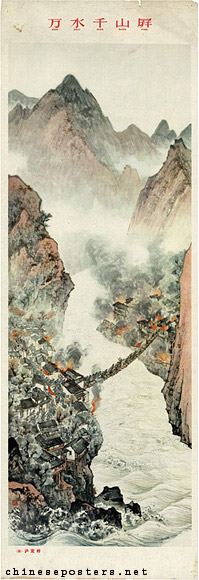

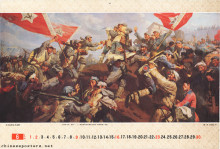

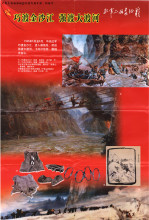

An arduous journey scroll (four). Luding Bridge, 1961

Already before the establishment of the People’s Republic, the Long March had become the central event in the Party’s representation of its history. Heroic stories were repeated over and over again, the sites where the events took place eventually became places of pilgrimage. The most spectacular events, especially the crossing of Luding Bridge served as inspiration for scores of paintings and posters.

An arduous journey scroll (eight). Northern Shaanxi, 1961

In 1961 a series of eight posters was designed by Ying Yeping (应野平) and Wang Huanqing (汪欢清). They are in the style of Chinese landscape paintings. The soldiers, their fighting and their heroic exploits are pictured almost as details in a magnificent, idealized scenery. The events themselves are idealized too; there are no wounded or dead, the soldier’s uniforms remain almost spotlessly clean, marching takes place in an orderly fashion, and the red flag is always carried in front. The absence of Party leaders is striking. Not even Mao is depicted on any of the eight posters. Around 1961 his position was far from undisputed, due to the failure of the Great Leap Forward for which he was held accountable.

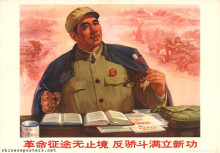

In the decades following the publication of the 1961 series, Mao’s role in the Long March was substantially reevaluated. This was partly the result of Mao’s elevation to unassailable heights during the Cultural Revolution. While the March as such continued to be seen as one of the defining moments in early Party history, the new interpretation of events focused on Mao’s actions and decisions as instrumental and decisive in the course of the March.

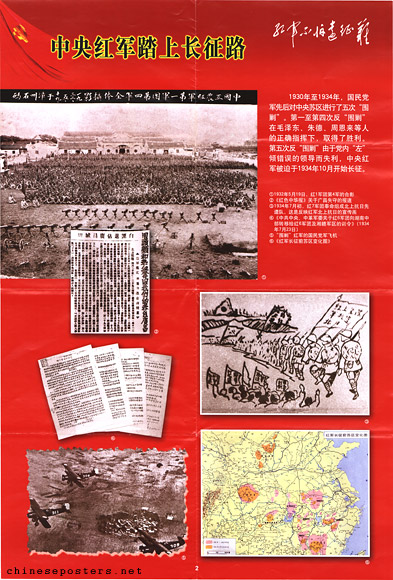

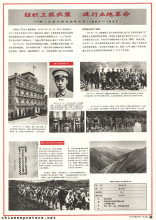

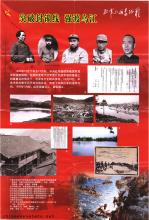

The Central Committee and the Red Army set out on the Long March, 2006

And yet, as a 12-sheet series published in 2006 shows, even though Mao-as-a-person was very much present in the visual recounting of the event, the actual narrative pays more attention to the collective character of the undertaking, to the crystalized interpretation of what (might have) happened during those months when the CCP and the Red Army struggled for their survival.

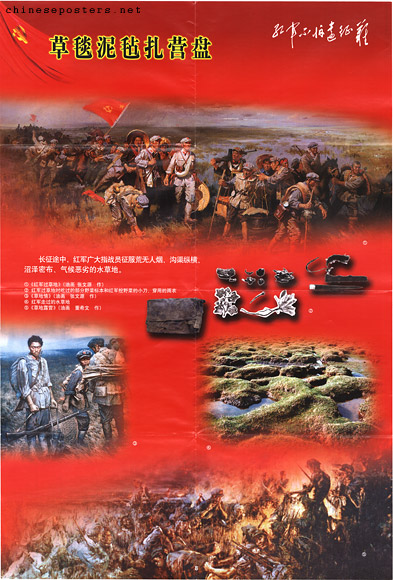

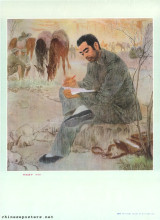

Camping in grass and mud, 2006

A comparison of the two sets shows that the evaluation of importance of events during and indivdual stages of the March has evolved, or changed. The battle at Lazikou, for example, is almost overlooked in the second series, whereas more space is given to the Party and Army units that stayed behind and covered the back of the main force moving to the Northwest. And of course, the roles of various participants in the March have been reevaluated as well.

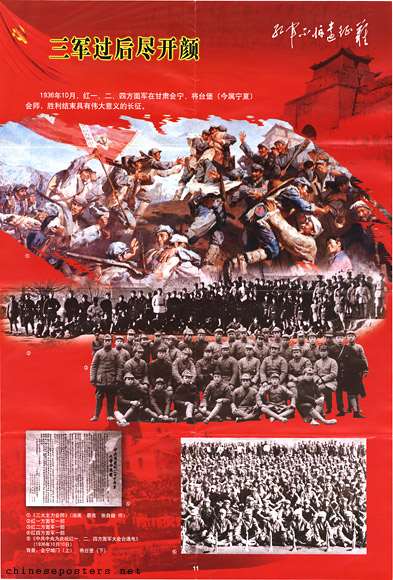

Great joy after three years of hardship, 2006

Another aspect that illustrates the passing of time is that the latter series reflects the technological and esthetic changes that have taken place in the intervening four decades. The comprehensive use of photo-montage of natural scenery and historical documents gives these modern posters more sense of urgency and verisimilitude, while lacking the poetic and dreamlike qualities that marked the older series. The recycling of earlier posters as illustrations of what might have been the real story and how events might have played out, on the other hand, indicates that the historical interpretation, while shifting over time, does not leave much room for alternative readings.

Enhua Zhang, "The Long March", in Wang Ban (ed.), Words and their stories -- Essays on the Language of the Chinese Revolution (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 33-49