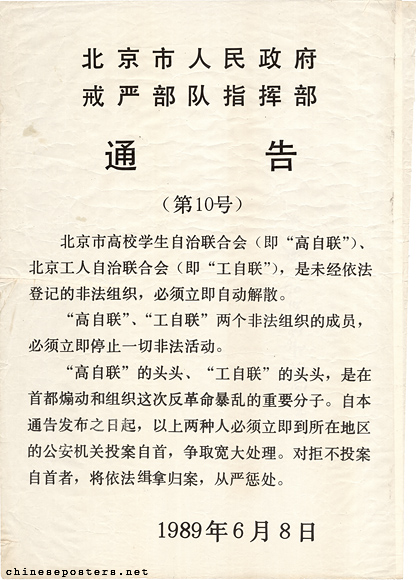

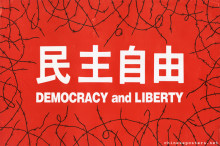

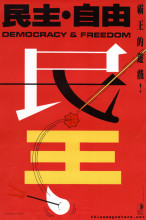

The bloodbath that took place in Beijing in the night of 3-4 June 1989 brought an end to weeks of peaceful demonstrations for a more democratic type of socialism in China. An unprecedented number of students, workers, peasants, journalists, intellectuals and even policemen and sympathetic soldiers, had gone out on the streets in all major Chinese cities to protest against the existing political order, calling for democracy, freedom of the press and an end to corruption. Many non-Party directed organizations sprung up, including the "Autonomous Students Union of Beijing Universities" (ASUBU); the Beijing Independent Intellectuals Association; the "Autonomous Workers’ Federation"; and others.

Reform and the death of Hu Yaobang

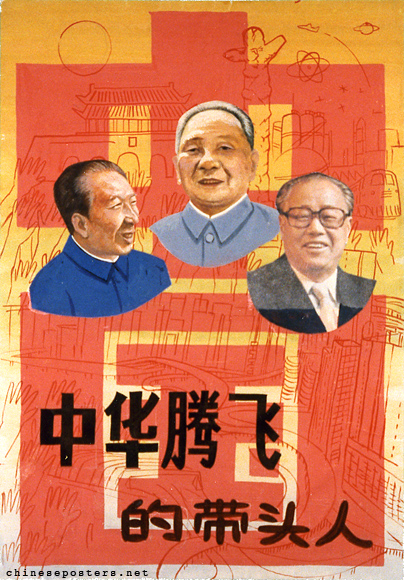

The leaders of China's take-off, 1989

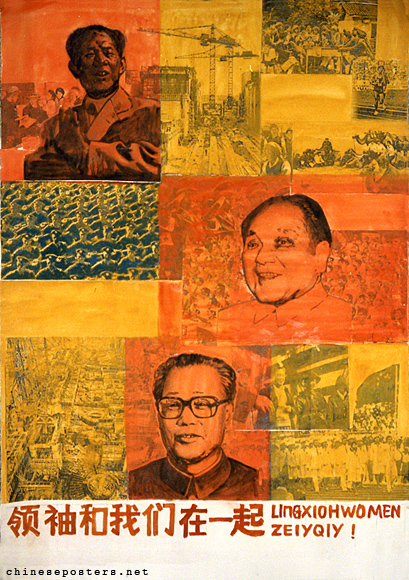

The leaders and we are together, 1989

The demonstrations started with the unexpected death of Hu Yaobang on 15 April 1989 and led to the bloody crackdown of what was termed a "counter-revolution". Hu, the Party General Secretary who was purged in 1987 after being held responsible for student demonstrations, became the movement’s symbol of political reform. His death formed the catalyst for the organized protests, but in the period preceding his demise, tensions already had been rising in society. One of the reasons for this was that the economic reforms had benefitted far smaller portions of the population than originally expected; not everybody was able to make out to the extent that many had hoped for when Deng Xiaoping's Reform and Opening Up proposals were implemented in late 1978. Crony capitalism and corruption were increasingly held responsible for this situation. Inflation had risen to alarming levels; the job market remained tightly controlled by the government; social reforms did not materialize. Moreover, many were convinced that political reforms, comparable to the perestroika that was implemented at the time in the Soviet Union, would make the traditionally secretive Chinese political scene more transparent, allowing for more oversight, more accountability, and more popular participation.

Gorbachev in Beijing

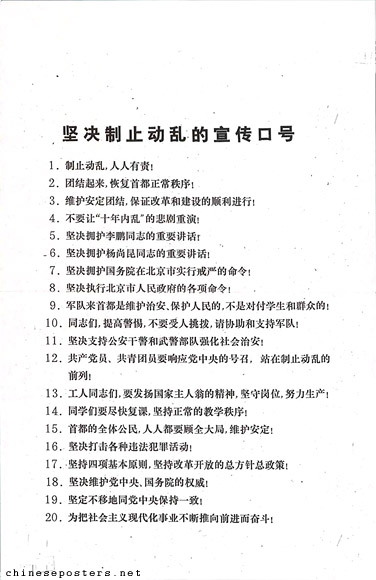

Propaganda slogans for resolutely stopping upheavals, 1989

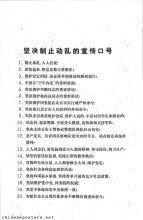

The events leading up to the massacre were extensively covered by the international media, who had flocked to the Chinese capital to report the historic visit of Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev (15-19 May), but who stayed on to inform the world about what seemed to be a popular revolution. The media's presence in Beijing has created the impression that the dissatisfaction was limited to the capital, but in reality, most of China's larger urban centers saw popular unrest. The Beijing events included massive demonstrations on Tian'anmen Square and in front of Zhongnanhai, the government compound to the west of the Forbidden City; futile attempts to offer popular petitions to the representatives of the National People's Congress; hunger strikes. The government, in an editorial published in People's Daily (Renmin ribao) on 26 April and based on a speech by Deng Xiaoping and the views of Chen Yun, Li Xiannian and Peng Zhen (members of a group of elderly leaders, including Zhou Enlai's widow Deng Yingchao, who were seen as the Party's "Immortals"), insisted that these actions should be considered as acts of "hooliganism" and part of a "planned conspiracy" aimed at overturning the Party. The editorial, entitled "It is necessary to take a clear-cut stand against disturbances" (必须旗帜鲜明地反对动乱), would remain a bone of contention. Zhao Ziyang, who was purged as a result of his support of the demonstrators, kept on stressing the patriotic nature of the movement.

The Goddess of Democracy

Miniature replica of the Goddess of Democracy, produced by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Democratic Movements in China.

Collection IISH, Amsterdam

The 10-metre-tall model of the Statue of Liberty, named the Goddess of Democracy (自由女神) and symbolizing the demonstrators' calls for democracy, in front of the Tian’anmen Gate Building on 29 May remains an iconic image. Built from metal, foam and papier-mâché by students of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, it reinvigorated the student movement, which was dwindling by this time. Its strength as a symbol can be gauged from the fact that the government more or less copied it for its own purposes shortly after.

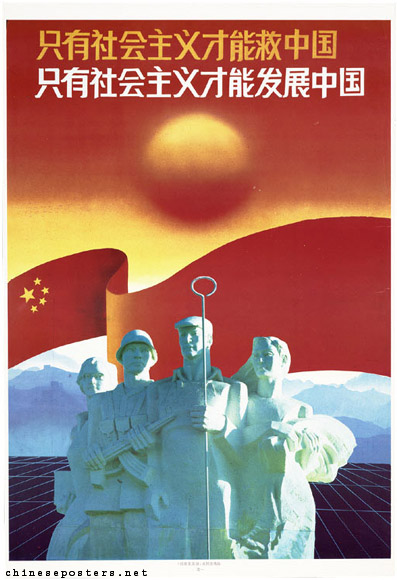

Only socialism can help China, only socialism can develop China, 1989

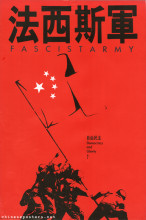

The Army moves in

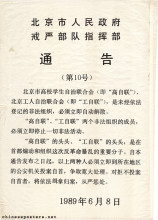

With the authorities unable to bring an end to the demonstrations, a state of martial law was declared by Premier Li Peng on 20 May. Some 250,000 troops were amassed around the city. By 1 June, leadership consensus was reached that it was necessary and legal to deploy the military to clear Tian'anmen Square of the protestors, who were termed as terrorists and counterrevolutionaries.

On 3 June, at 18:30, the Beijing Municipal Government and the Martial Law Headquarters issued an emergency notice urging all Beijing residents not to go onto the streets or to go to the square. At 22:00, troops received the orders to proceed to the center of the city and to clear the square by 6:00 am the following morning. Shortly after midnight, hundreds of tanks and armored car columns moved in from the west; during their advance along Chang'an Avenue, pitched battles between civilians and troops were fought at the Shoudu Iron and Steel Works, at Fuxingmen, at Muxidi, at Liubukou, at Xidan and at Yongdingmen. Troops used automatic rifles, explosives, bayonets and tanks against protesters and unarmed citizens, trying to block their advance. At least 500 people were killed in these skirmishes. After breaking through the barricades thrown up by the people, tanks and armored cars encircled Tian'anmen; using the network of underground tunnels, thousands of soldiers appeared from everywhere to enter the square and crack down ruthlessly on the people left there. From the east, columns of tanks and armored cars entered the city shooting at everything that moved; the encirclement of Tian'anmen was completed and the square was turned into a military encampment. People seeking refuge in the allies and hutong near Tian'anmen were killed by troops and security police. The Red Cross Society of China estimated the number of casualties to be 2,600.

After this announcement, the Army moved into the hospitals and took over, clearing out the dead and the wounded; all medical assistance to wounded civilians was forbidden. Armed skirmishes between troops and civilians continued all day; troops opened fire on innocent bystanders; citizens turned against soldiers, hanging them, sometimes dousing them with gasoline and setting them on fire. In the afternoon, State radio announced that the Army had achieved a great victory in cracking down on an "extremely small group of people attempting to overthrow the Communist Party and the socialist system and to topple the People’s Republic of China". In Chengdu, protests continued while news of the Beijing massacre was trickling through. After nightfall, the use of teargas was stopped and large numbers of security forces moved in, wielding truncheons, knives and electric cattle prods; groups of demonstrators were isolated and beaten and stabbed. Casualty estimates ranged from 10 to 300 people. On 7 June, the Jianguomenwai diplomatic compound in Beijing was fired on and surrounded by troops in an effort to intimidate the foreign community.

Aftermath

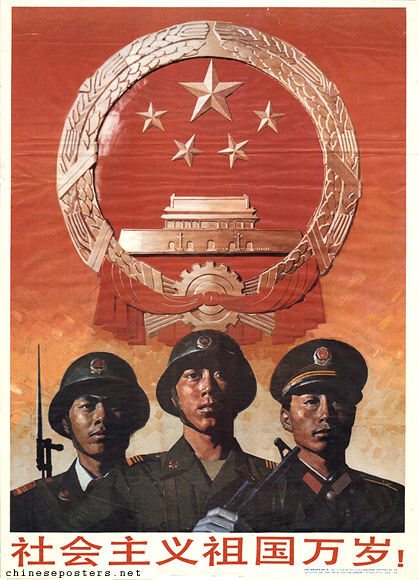

Long live the socialist mother country!, 1989

On 9 June, Deng Xiaoping, accompanied by Yang Shangkun, Li Peng, Qiao Shi, Yao Yilin, Wan Li, Wang Zhen, Peng Zhen, Bo Yibo, Li Xiannian, and others, and a number of generals (including Chi Haotian, Yang Baibing and others) appeared on television, praising military commanders for their suppression of the demonstrations on 4 June. Chen Yun, although not present, sent a message of support. Deng delivered a speech that formed the basis of the official version of the suppression and in which he formulated future policy. In the weeks following, large numbers of participants in the demonstrations were rounded up, subjected to (often televised) trials and convicted. Video footage from traffic cameras installed in urban districts, as well as the the newscasts by foreign media, proved helpful in identifying these participants.

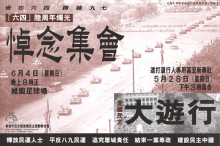

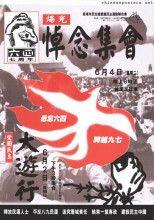

Participants who were able to escape arrest, both within the country and abroad, and both in secret and openly, were forming organizations and planning actions that would continue the struggle for democracy, for ending one-party rule and for developing a more open economy responding to market forces. Meanwhile, the suppression of the movement by the Army led to international indignation and sanctions, including (temporary) suspension of diplomatic relations.

Even now, our understanding of the underlying social and political causes and currents remains fragmentary. The considerations of political and personal power that prompted State, Army and Party leaders to call in the People’s Liberation Army to annihilate the protesters remain equally shrouded in secrecy. The ensuing attempts by the Chinese leadership to restore order by an intimidation campaign, executing "ringleaders" of the movement, and by excluding all accounts of the events different from its own (officially published on 14 June), have contributed to our moral outrage, but not to our understanding.

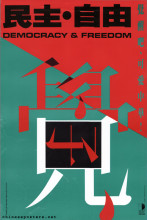

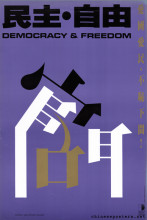

Advance bravely along the road of socialism with Chinese characteristics, 1989

During the demonstrations themselves, great numbers of documentary materials, including pamflets, declarations, etc. were published; parts of these collected materials are accessible at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. As for propaganda posters, the developments took place too fast and were too diverse to react to. Moreover, many artists and designers, as well as those working in the publication and distribution structure, sympathized with the demonstrators. A great number of the posters published in 1989 and 1990 are arguably related to government attempts to strengthen popular support, paper over any antagonistic sentiments among the people, show strength, and honor the military that was forced to open fire on its own people. The main themes of these posters are nationalism, echoing the Socialist Patriotic Education Campaign that was unleashed after the massacre; and the strength of the military. Unity among the people is a topic only gingerly addressed.

Elaine Chan, "Structural and Symbolic Centers -- Center Displacement in the 1989 Chinese Student Movement", International Sociology 14:3 (1999), 337–354

Chen Xitong, Report on Checking the Turmoil and Quelling the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion (Beijing: New Star Publishers, 1989)

Arif Dirlik, "Forget Tiananmen, You Don't Want to Hurt the Chinese People's Feelings -- and Miss Out on the Business of the New 'New China'!", International Journal of China Studies (2014) (https://truthout.org/articles/forget-tiananmen-you-dont-want-to-hurt-the-chinese-peoples-feelings-and-miss-out-on-the-business-of-the-new-new-china/)

Stefan Landsberger, “Appendix: Chronology of the 1989 Demonstrations”, in Tony Saich (ed.), The Chinese People’s Movement -- Perspectives on Spring 1989 (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe Inc. 1990), 164-189

Louisa Lim, The People's Republic of Amnesia -- Tiananmen Revisited (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014)

Shu-Yun Ma, "The Role of Power Struggle and Economic Changes in the ‘Heshang phenomenon’ in China", Modern Asian Studies 30:1 (1996), 29-50. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00014074

Frank N. Pieke, The Ordinary and the Extraordinary: an Anthropological Study of Chinese Reform and the 1989 People's Movement in Beijing (London: Kegan Paul International, 1996)

Jonathan Unger (ed.), The Pro-Democracy Protests in China: Reports from the Provinces (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1991)

Chaohua Wang, "Diary", London Review of Books 29:13, 5 July 2007

Guobin Yang, "Achieving Emotions in Collective Action: Emotional Processes and Movement Mobilization in the 1989 Chinese Student Movement", The Sociological Quarterly 41:4 (2000), 593-614

Dingxin Zhao, "Decline of Political Control in Chinese Universities and the Rise of the 1989 Chinese Student", Sociological Perspectives 40:2 (1997), 159-182

Suisheng Zhao, "A State-Led Nationalism: The Patriotic Education Campaign in Post-Tiananmen China", Communist and Post-Communist Studies 31:3 (1998), 287–302

Zhou He, Mass Media and Tiananmen Square (Commack: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 1996)

- Inventory Collection Chinese People's Movement (IISH, Amsterdam)

- Tiananmen Square protests, 1989 (IISH, Amsterdam)

In collaboration with the Sinological Institute in Leiden, the IISH has collected pamphlets, wall-posters, photographs, newspapers, video and audio recordings, objects, and other materials, during and briefly after the 1989 protest movement that centered in Beijing, but spread to other big cities in the country. The collection also holds some documents concerning Chinese social movements and student demonstrations in the 1980s.