China and the Soviet Union concluded a 30-year Treaty of Peace, Security and Friendship on 14 February 1950. The PRC, lacking an economic base and administrative-technical skills, was willing to play the role of 'little brother' in the fields of ideology and foreign policy, in return for extensive (financial, material and immaterial) support from Moscow. Economic cooperation was an important component of the Treaty and enable China to achieve impressive industrial development and growth. It also helped supply Soviet weapons and equipment to modernize the Chinese armed forces from a primitive mass-based army into a semi-modern fighting force. In the early 1950s, in short, the Soviet Union, the first country that alleged to have "realized communism", in many if not most respects provided a shining example for Peking.

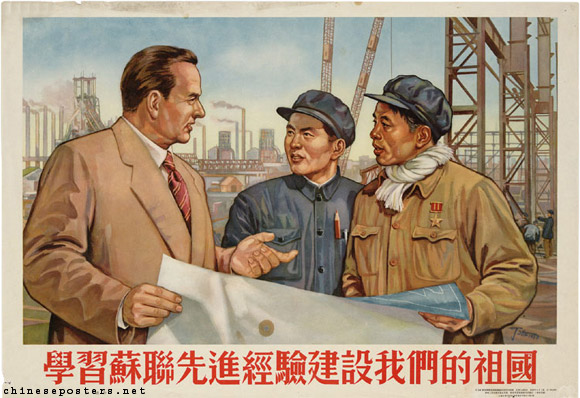

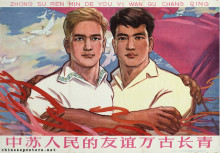

The Soviet Union is our example, 1953

The CCP also sought inspiration in the Soviet Union for the development of its visual propaganda. Mao and other leaders were convinced that Socialist Realism, as it had been practised in the Soviet Union since the 1930s, was the best tool to develop new forms of art. It provided a realistic view of life, represented in the rosy colors of optimism, although largely seen through an urban lens. Socialist Realism focussed on industrial plants, blast furnaces, power stations, construction sites and people at work. In the period 1949-1957, many Chinese painters studied Socialist Realism in Soviet art academies; others were educated by Soviet professors who came to teach in Chinese institutions.

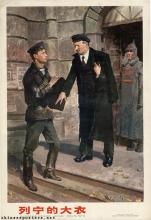

In those years, a large body of posters was published to familiarize the Chinese workers with the phenomenon of the Russian teacher who would be assisting them. The Soviets were friends, the 'elder brother' (laodage) to whose side China had decided to lean in order to learn everything about modernization. The tone seemed to be set by the many propaganda posters that showed Mao Zedong together with Joseph Stalin (Стaлин). In these images, obvious artists' impressions of Mao's visit to Moscow in 1949-1950 during the negotiations for the Treaty, Mao and Stalin invariably stood on the same level.

This representation, which appeared in other visual materials as well, was in direct contradiction with the actual relationship between the two countries. China had decided after all to enter into this bilateral alliance as a junior partner, making it an essentially unequal relationship.

Most posters devoted to the Soviet support of Chinese reconstruction treat the topic with a certain degree of unease. Although the Chinese obviously are gratified that they can follow the Soviet example, there is a feeling of distance between the represented Soviets and Chinese. The 'elder brother', of course, usually is shown in the position of the teacher. The Chinese are pictured as the attentive pupils, absorbing every word uttered by their teacher. As a result, these images do not seem to be filled with deep feelings of international proletarian solidarity, or class brotherhood. Instead, there is a pervasive feeling of Soviet condescension towards the eager, but seemingly insecure Chinese pupils. The latter, in turn, do not look grateful, but rather envious.

Study the Soviet Union's advanced economy to build up our nation, 1953

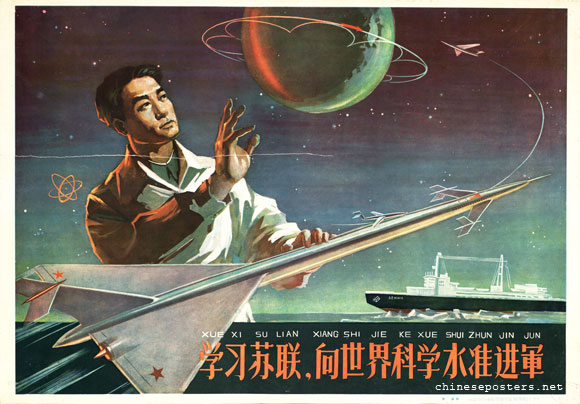

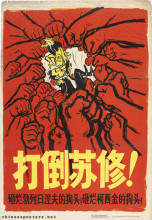

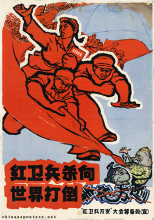

In later years, growing dissatisfaction with following this foreign example, as well as a greater concern with the validity of China's own revolutionary experience, provided the causes for the Sino-Soviet split. One of the Chinese assertions that caused the estrangement was its perception that concerted mass movements such as the Great Leap Forward could bring about communism faster than the experiences provided by the Soviets. Moreover, the Chinese accused the Soviets of looking for technocratic instead of revolutionary solutions and increasingly neglecting ideology in favor of "goulash communism", i.e., providing its people with material comfort.

Study the Soviet Union, to advance to the world level of science, 1958

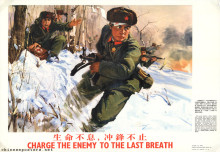

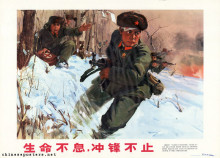

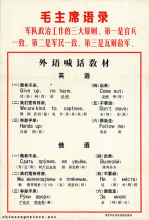

The conflict, which came to a head at Damanski, or Zhenbao, Island in 1969, during the Cultural Revolution, was to last until 1989.

Lyle J. Goldstein, "Return to Zhenbao Island: Who Started Shooting and Why it Matters", The China Quarterly No. 168 (2001), 985-997

Austin Jersild, "Socialist exhibits and Sino-Soviet relations, 1950–60", Cold War History (2018), 1-15

Charles Kraus, "Laying Blame for Flight and Fight: Sino-Soviet Relations and the 'Yi–Ta' Incident in Xinjiang, 1962", The China Quarterly (2019), 1-20

Lorenz M. Lüthi, The Sino-Soviet Split -- Cold War in the Communist World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008)

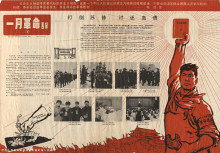

The Damanski - Zhenbao conflict

Sino-Soviet Relations  , National Intelligence Estimate Number 100-3-60 (9 August 1960), declassified by the CIA in October 2004

, National Intelligence Estimate Number 100-3-60 (9 August 1960), declassified by the CIA in October 2004