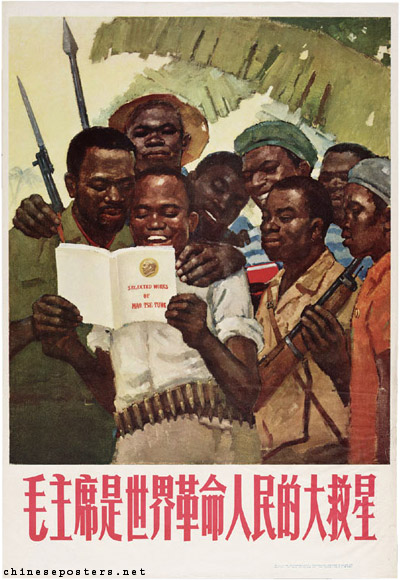

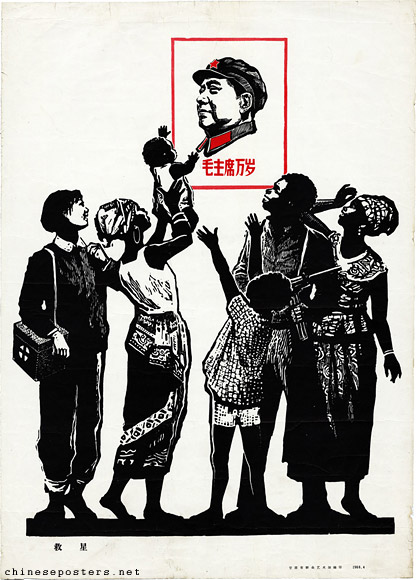

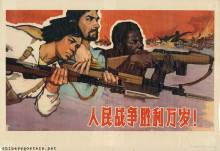

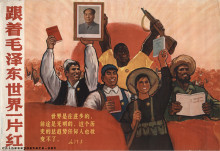

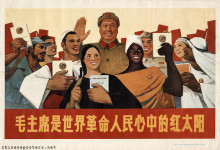

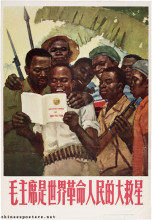

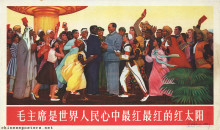

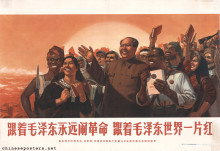

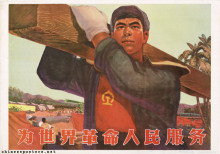

Chairman Mao is the great liberator of the world's revolutionary people, 1968

The appearance of colored peoples, and blacks in particular, in Chinese propaganda posters always has been problematic. Before the CCP grasped power, the only attention devoted to colored peoples in Chinese art was of a negative tone. Once the PRC was established, however, this attitude changed. Now that racial problems were seen as class problems, China increasingly discovered similarities between its own traumatic experiences with 'white imperialism' and those of other victimized 'colored' people in the world. It was time to downplay the traditional and deeply ingrained feelings of superiority. One of the first official steps to gain credibility as a supporter of the oppressed was taken in September 1950, when the Chinese lodged an official protest against the policy of apartheid in South Africa. Africans soon became regular guests in Beijing, where they were entertained at parties and met with the highest state leaders. By the late 1950s, many delegations had passed through Beijing and Zhongnanhai. But the Chinese did not actively spread the gospel of revolution and national liberation yet. They merely positioned themselves as a model that needed to be followed to gain independence.

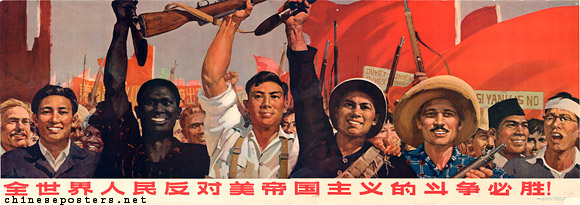

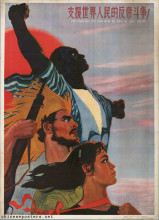

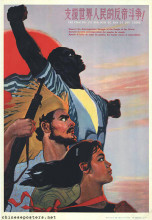

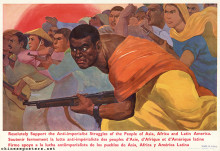

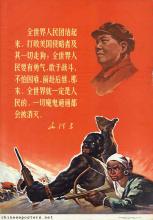

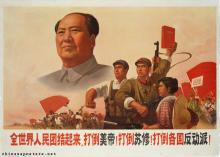

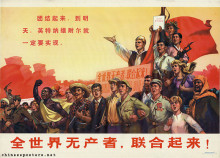

The struggle of all the people in the world against American imperialism will be victorious! 1965

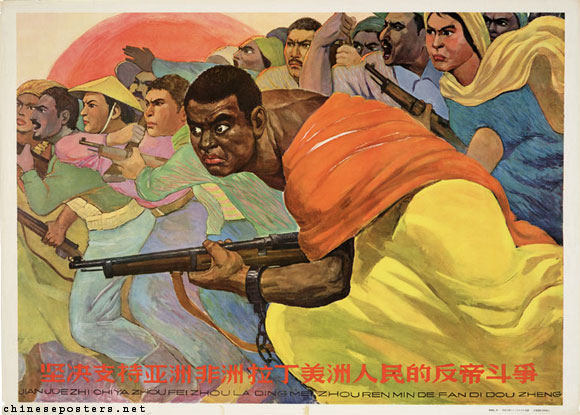

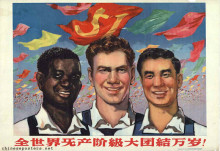

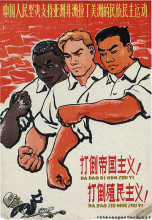

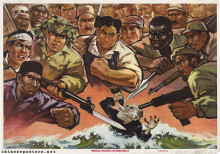

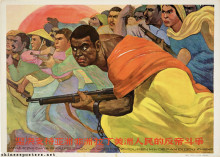

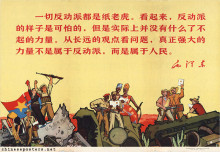

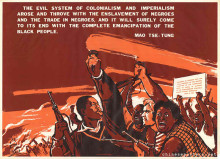

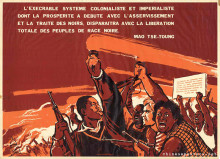

In the early 1960s, during the opening moves of the Sino-Soviet split, the Chinese very much played the color card in order to trump up their own status of oppressed colored people. They stated that yellow and black might not be the same, but at least it was not the white of the Soviets. At the time, Mao had become convinced that Africa would become the battlefield where the power of the West could be destroyed and the world revolution could be started, and that China, instead of the Soviet Union, would be the leader of this historical struggle. To support this bid for the leading position in the world revolution, China began to give military support, ranging from weapons, funds, food, medicine and lorries to actual training courses at the Nanjing Military Academy. The African students were very much schooled politically and trained in the CCP guerrilla experience. In late 1963, Zhou Enlai, accompanied by Chen Yi, visited a number of African countries, spreading the revolution. Around the same period, colored peoples appear in propaganda posters for the first time.

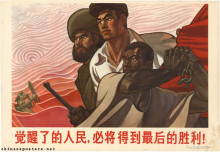

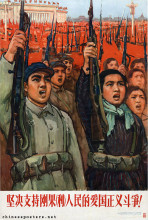

In the first few years of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1967), African independence struggles were supported actively. This support partly resulted from the ideological viewpoint that Africans (and other peoples from under- and undeveloped nations) represented the countryside that was in the process of surrounding the cities (the developed world). The Chinese insisted that this strategy had been tested successfully by the CCP itself in the War of Liberation, and had resulted in the founding of the PRC, which had imbued the Chinese people with enormous pride and self-confidence. Lin Biao had asserted as much in his Long Live the Victory of People's War in 1965. On the other hand, China's interest in Africa was grounded equally in a desire to steal away as many former African allies of the Soviet Union as possible. This was to give support to the Chinese view that they were the true leaders of the international revolutionary movement, having eclipsed the Soviets who now were considered revisionists.

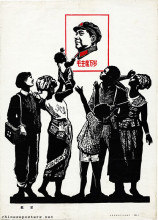

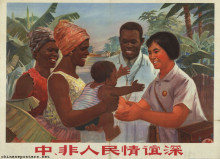

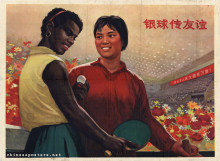

The friendly relations with dignitaries from the newly-independent African nations, or with leaders of African liberation movements that were supported by Beijing, resulted in a flood of photographs and newsreels devoted to the highest Chinese leaders, including Mao himself, receiving these African leaders. Despite the endless paeans in the Chinese media testifying to the revolutionary fervor sweeping the continent, an extremely small number of posters has been devoted exclusively to Sino-African friendship and the Chinese support that resulted from it. If Africans appear at all, they usually participate in revolutionary mass scenes. An interesting contrast exists between the photographs and such posters devoted to struggle. Many of the African visitors photographed by Xinhua while being received in Zhongnanhai, in particular the leaders of the independence movements, were kitted out in battle dress, or camouflage. The postered Africans, however, most frequently are dressed in their distinctive national garb of flowing robes. Although it most certainly looks more dramatically than army fatigues, it smacks of a clichéd way of rendering Africans as 'noble savages'. Moreover, it must have been a cumbersome way of dressing for the battlefield.

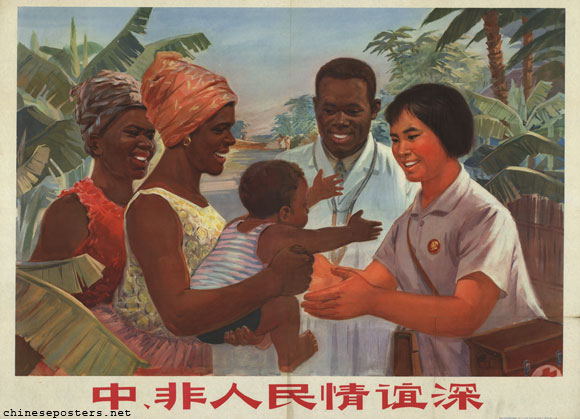

The feelings of friendship between the peoples of China and Africa are deep, 1972

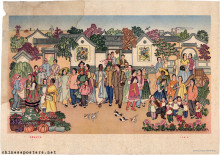

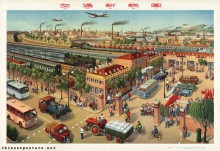

Other types of posters, however, very much supported the official position that China was in a position superior enough to be able to help Africans. As far as we know only very few posters were made that were devoted to, for example, the much vaunted TanZam or Tazara Railway, built between 1968 and 1976 and linking Tanzania and Zambia. But the quality and type of support the Chinese rendered to Africa in this case very much provided the template for the images concerning Africa and Africans: the Chinese are giving, the Africans are on the receiving end.

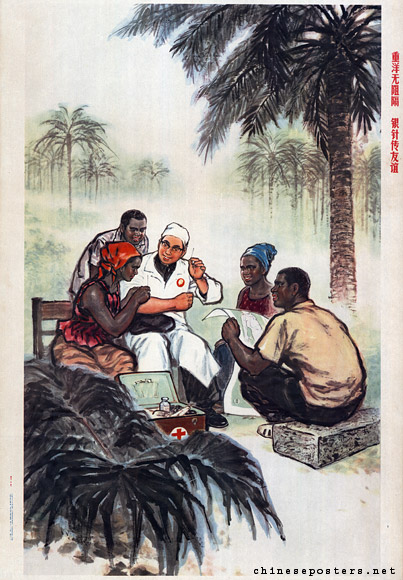

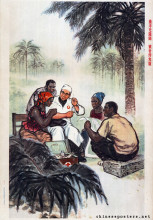

Seas and oceans are not separated, the silver needle passes on friendship, 1971

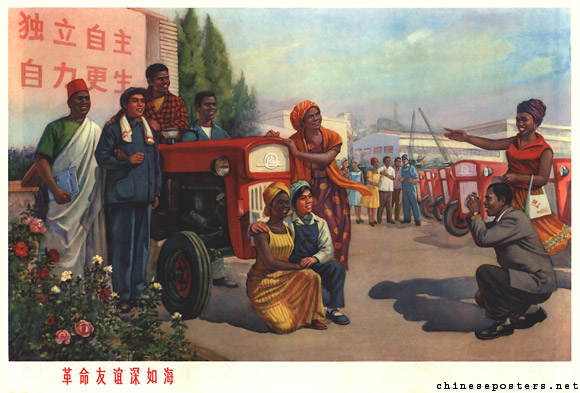

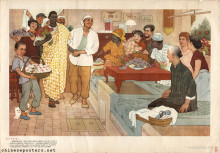

Thus, we see a Chinese barefoot doctor in action in Africa, tending to black patients. Basic medical care, often based on Traditional Chinese Medicine was provided to the poorest parts of the poorest countries by Chinese doctors and medical workers. We see delegations of African representatives, including women in colorful national garb, visiting a model town, enjoying themselves at the Great World Entertainment Center in Shanghai, and walking in awe on the Yangzi Bridge at Nanjing. We see African delegates posing for a photograph in front of a tractor at a Chinese tractor plant.

Revolutionary friendship is as deep as the ocean, 1975

Africa and China drifted apart with Deng Xiaoping's accession to power in 1979. Many Africans were not able to accept the sudden and surprising changes of political line, and the way Mao's memory, and his surviving supporters were treated. Many considered the way Mao's widow Jiang Qing was treated uncivilized. Many others found it hard to swallow that the Chinese ideological somersault of the 'Four Modernizations' was preached with the same fervor as the message of revolution that was spread before. In short, China lost so much of its credibility that it could be seen no longer as an example.

In the 00s, African attitudes towards China shifted again. Thanks to China's "Peaceful Rise" or - less threatening - "Peaceful Development", economic instead of political relations have started to dominate Chinese-African ties. Whereas Western nations and institutions try to attach various strings to their economic assistance and loans to African nations, China doesn't. Holding true to its policy of non-interference in internal affairs, Beijing does business with any African nation that offers energy resources or raw materials that can feed China's economic machine, regardless of its record in the fields of human rights, good governance or other pet concerns of Western nations and NGOs. This leads to bitter accusations of China's behavior.

Joshua Eisenman, "Comrades-in-arms: the Chinese Communist Party’s relations with African political organisations in the Mao era, 1949–76", Cold War History (2018), 1-17

Robeson Taj Frazier, "Making Blackness Serve China: The Image of Afro-Asia in CHinese Political Posters ", Leigh Raiford, Heike Raphael-Hernandez (eds.), Migrating the Black Body: The African Diaspora and Visual Culture (Washington: University of Washington Press, 2017)

Richard Hall & Hugh Peyman, The Great Uhuru Railway - China’s Showpiece in Africa (London: Victor Gollancz, 1976)

Melissa Lefkowitz, "Revolutionary Friendship: Representing Africa during the Mao Era", Kathryn Batchelor, Xiaoling Zhang (eds), China-Africa Relations. Building Images through Cultural Co-operation, Media Representation, and Communication (Milton: Taylor and Francis, 2017), 29-50

Lin Piao (= Lin Biao), Long Live the Victory of People’s War! (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1965)

Peter van Ness, "China and the Third World: Patterns of Engagement and Indifference", Samuel S. Kim (ed), China and the World - Chinese Foreign Policy Faces the New Millennium (Boulder: Westview Press, 1998)

Secretariat of the Afro-Asian Journalists’ Association (ed), Selections of Afro-Asian People’s Anti-Imperialist Caricatures (Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe, 1967)

Philip Snow, The Star Raft - China’s Encounter with Africa (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988)

Jeremy Youde, "China's Health Diplomacy in Africa", CHINA: An International Journal 8:1 (2010), 151-163