China's participation in World Exhibitions has been quite longstanding. Chinese merchants, as well as foreign merchants doing business in China, were present at the first World Exhibition, the London Crystal Palace Exhibition held in 1851. They brought traditional Chinese goods, such as silk, tea, and medicine to the Exhibition. Many of these exhibits received awards. Over the years, China would participate in most World Exhibitions; in 1876, China for the first time sent official delegates to the Philadelphia World Exhibition. In 1929, China held its own Exhibition in Hangzhou, Zhejiang—the West Lake Expo. Internal and external tensions, as well as policies and attitudes towards other nations, made Chinese participation impossible for a number of years. Only since 1982, at the World Expo in Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S.A., the PRC has again taken part in World Exhibitions, for the first time as the "new" China. This was also intended to concretely show its Reform and Opening Up policy.

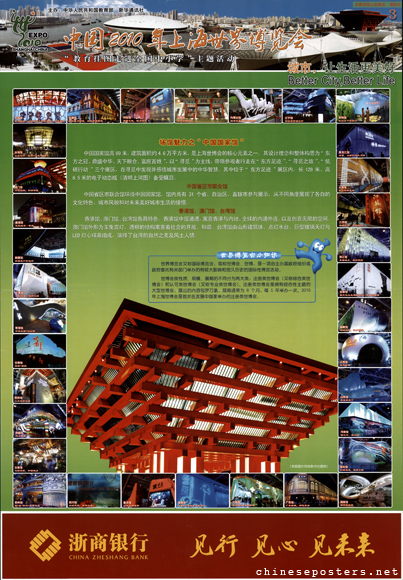

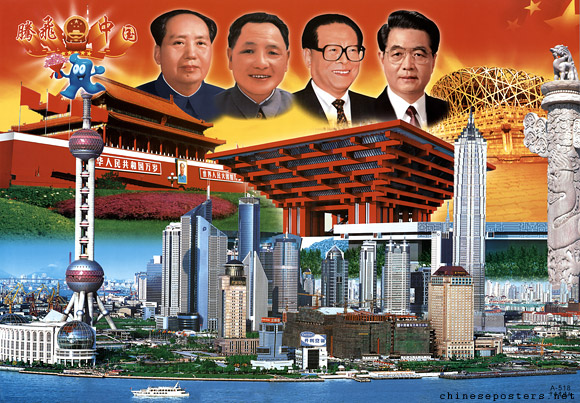

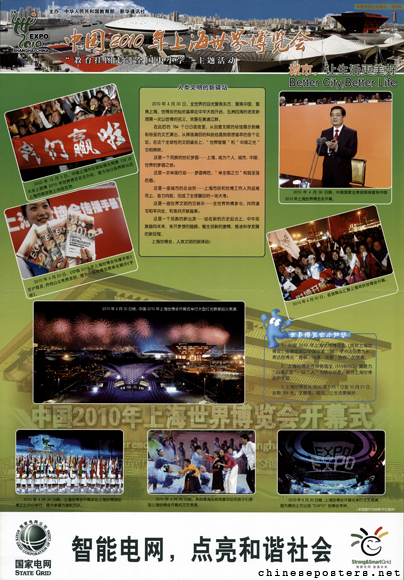

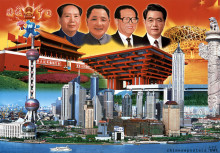

The Expo 2010 Shanghai China (中国2010年上海世界博览会), shortened to Expo 2010 (世博会2010), took place from 1 May to 31 October 2010. The event capped three successive years of major events (the Beijing Olympics 2008; the 60th anniversary of the PRC in 2009; and the Expo, supposed to be like a second, or Economic Olympics) that all to a greater or lesser extent were intended to increase China’s international stature and provide a counternarrative to western discourses that encoded China’s rise to global power as a threat to the international order. The exhibition grounds were located in the Nanpu Bridge–Lupu Bridge region in the center of Shanghai, along both sides of the Huangpu River, covering 5.28 km2, the biggest in history. When it ended, more than 73 million people had visited the pavillions and exhibits of 192 nations (including Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), 40 international organizations and 10 non-governmental organizations. Some 90% of the visitors were from China, many having received free government tickets or visiting as part of a special deal. Many, mainly foreign, observers interpreted this as a failed attempt to influence global opinion; in reality, it appears that from the onset, the organizers of Expo 2010 saw the domestic audience as its main target. While a massive official PR campaign accompanied the event, this does not explain why so little printed propaganda was published in the run-up to and during the Exhibition, specifically focused on the Expo, especially when compared with the propaganda output of the Olympics. The set of posters presented here is the only body of materials we have been able to acquire. Moreover, they carry advertising, by, amongst others, the State Grid, China Post, China Zheshang Bank, China Eastern (airline), China Minsheng Bank, Mengniu (dairy). Some of the exhibits and pavilions, most importantly the China Pavilion, did assume an iconic presence in other propaganda posters.

The official theme of the Expo was "Better City – Better Life" (城市,让生活更美好, which translates as "the city makes life more beautiful"). As Jennifer Hubbert argued, "While the English version (of the motto) intimates that improving cities will enhance urban life—i.e., that making cities better will make citizens’ lives better—a literal translation of the Chinese version more explicitly expresses the state’s massive urbanization-centric development model: 'Cities Make Life Better'. This translation implies that urbanization itself improves lives, not the specific nature of the urban spaces ... In other words, the Chinese version of the theme insinuates that urban spaces improve lives, with no regard to the quality of those urban spaces or aspiration for improvement".

Five pavilions were specifically dedicated to showcasing the Expo theme. These were the Urbanian Pavilion (城市人馆), showcasing five elements of urban life (home, work, connectivity, learning, and health) as experienced by six families in six cities from different continents (Phoenix, Sao Paolo, Tema, Rotterdam, Zhengzhou, and Melbourne); the Pavilion of City Being (城市生命馆), promoting the story of modernity and progress; the Pavilion of Urban Planet (城市地球馆), presenting dystopian scenarios of urban sprawl, scorched earth, and polluted seas, and showcasing solution in the form of low-carbon construction techniques and green energy technologies; the Pavilion of Footprints (城市足迹馆), showcasing various historical examples of city planning; and the Pavilion of Future (城市未来馆), presenting diverse science-fiction visions of future cities. Aside from the national and official pavilions, there were sculpture gardens, shops, a sports arena and clam-shaped performing arts centre to be visisted. The official Expo 2010 mascot was Haibao ("jewel of the sea", 海宝). According to some, it resembled the cartoon character Gumby that was shown on American television from the 1950s–1960s; according to others, it looked more like a blue-colored SpongeBob SquarePants.

One of the eye-catching national pavilions was the China Pavilion, the largest national pavilion at the Expo with a footprint of more than 71,000 m2 and a gross floor area in excess of 160,000 m2. The building was located halfway along the Expo Axis on its eastern side in Zone A of the Expo Park. The pavilion lay directly to the east of the Theme Pavilions and to the north of the Hong Kong and Macau pavilions. The chief architect was He Jingtang, the director of the Architectural Academy of the South China University of Technology. The 63-meter high pavilion, the tallest structure at the Expo, was dubbed "The Oriental Crown" (东方之冠) because of its resemblance to an ancient Chinese crown. The architectonic feature of the building was inspired by traditional Chinese interlocking wooden roof brackets known as dougong (斗拱). The exterior was painted in various shades of Chinese red, symbolising Chinese culture and good fortune. Unlike most of the other pavilions, the China pavilion was not dismantled following the Expo. On 1 October 2012, the China pavilion was reopened as the China Art Museum.

The Opening Ceremony on 30 April 2010, presided over by Hu Jintao, consisted of indoor festivities featuring performances by Jackie Chan, Japanese singer Shinji Tanimura, concert pianist Lang Lang and opera star Andrea Bocelli among the 2,300 performers. Afterward, guests moved outside for a lights, music and fireworks jubilee that lit up the banks of the Huangpu river with 1,200 searchlights, powerful lasers and mobile fountains. The waters glowed with 6,000 rosy-hued LED balls and lights from a parade of flag boats representing nations participating in the Expo. Part of these outdoor spectaculars was the then world’s largest LED screen at 265m long and 32m high. The Closing Ceremony, on 31 October 2010, presided over by Wen Jiabao, was a considerably more modest affair.

Maura Elizabeth Cunningham & Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, "China Discovers World Expo Is No Olympics", YaleGlobal Online (17 August 2010)

Jennifer Hubbert, "Better City, Better Life? Urban Modernity at the Shanghai Expo", The Asia-Pacific Journal 17:4-3 (2019)

Lucio Lamberti, Giuliano Noci, Jurong Guo, Shichang Zhu, "Mega-events as drivers of community participation in developing countries: The case of Shanghai World Expo", Tourism Management 32 (2011), 1474-1483&

Samuel Y. Liang, "The Expo Garden and Heterotopia: Staging Shanghai between Postcolonial and (Inter)national Global Power", The Asia-Pacific Journal 9:38-1 (2011)

Adam Minter, "Exquisite Fakes and Real Caesarean: Shenzhen's Subversive Expo 2010 Pavilion", Shanghai Scrap (https://shanghaiscrap.com), 5 August 2010

Florian Schneider, "The Futurities and Utopias of the Shanghai World Exposition -- A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of the Expo 2010 Theme Pavilions", Asiascape Occasional Papers 7 (June 2013)