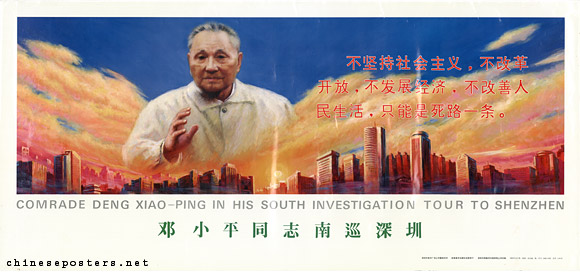

Comrade Deng Xiaoping in his South Investigation Tour to Shenzhen, 1992

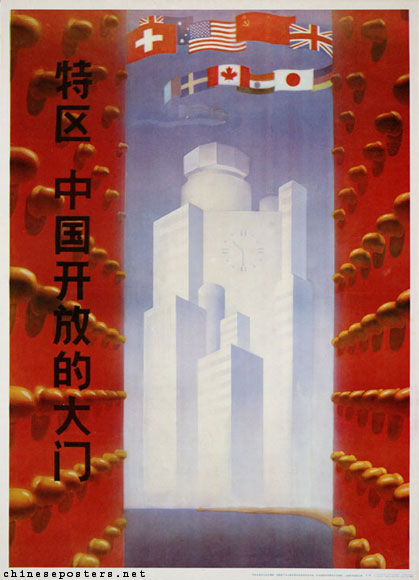

In 1977, Hua Guofeng started the Open Door policy, which was incorporated in the developmental "Four Modernizations" blueprint of Deng Xiaoping in 1978. By opening its doors to the outside world, China would be able to attract foreign investment which in turn would contribute to the modernization of both production processes and the Chinese product mix. Through the setting up of Special Economic Zones (SEZ) in Southern China, where bureaucratic interference, stifling rules and tax burdens were envisioned to be cut back, foreign companies were lured into cooperation with Chinese industrial complexes. Such cooperation preferably should take the form of joint ventures, in which the Chinese side would contribute raw materials, soil, infrastructure and (cheap) labor, and the foreign partner would supply advanced technology and production processes. In a later stage, even wholly-owned foreign companies were allowed to profit from the PRC’s relatively cheap labor and less stringent zoning rules, for example those concerning possible environmental damages. The best known SEZ intially were Shenzhen, North of Hong Kong, and Xiamen, opposite Taiwan. Later, cities along the seaboard, including Shanghai, were "opened up" and given a status that is comparable to SEZ. In the late 1980s, practically every Chinese city or township had opened its own "Science and Technology Development Zone", where conditions were similar to those of the SEZ.

Special Economic Zones - The Gateways to China, 1987

The benefits ascribed to the SEZ never really materialized. Instead of export bases of industrial production, the factories produced for the domestic market. Instead of joint ventures with foreign companies, domestic companies set up shop. Soon, SEZ were equated with corruption and land speculation. Many Chinese considered goods produced in the SEZ as the acme of sophistication. Whatever the worth of the SEZ, they in a sense did function as laboratories, offering the leadership opportunities to experiment.