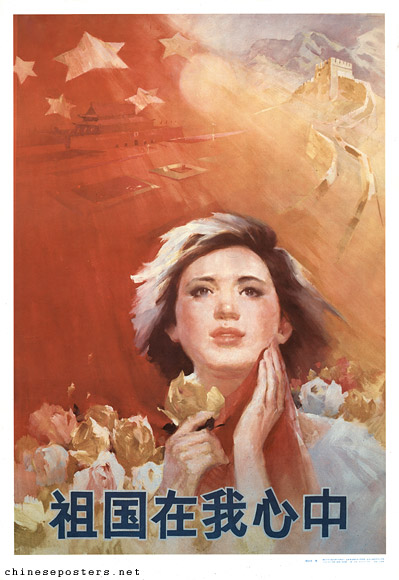

I carry the mother country in my heart, 1990

Since the 1980s, and especially since the Tian'anmen Massacre and the fall of the Soviet Union, China’s leaders have been promoting "patriotic education". The CCP faced a crisis of legitimacy, and Party elites were well aware of this. In 1989, the party leadership attributed the student demonstrations to failures in steeping the younger generations in revolutionary history. The CCP initiated the Patriotic Education Campaign to reorient the party’s ideological position. All elements of this new strategy were aimed at replacing Marxism-Leninism, which the party-state now considered outmoded, with a new nationalist theme.

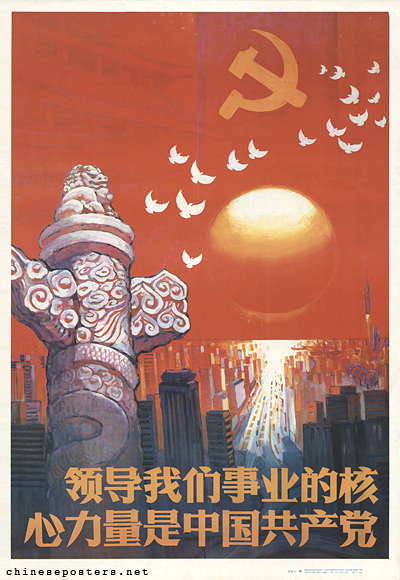

The Chinese Communist Party is the core force guiding our endeavours, 1989

New official discourses depicted the CCP as the key actor for invigorating China, its central mission defending of national interests. The Party institutionalized this change in ideology through an increased use of patriotic rhetoric in the People’s Daily (Renmin ribao, 人民日报). In addition to initiating intensive patriotism education, the CCP implemented a reform of history education. This reform rewrote the fundamental narrative of modern Chinese history. Instead of emphasizing class struggle as a core justification for Communism, the new history curriculum highlighted the national humiliations of the modern era. According to the new official narrative, the CCP was more than the voice of the proletariat; it also ended the history of China’s hundred years of humiliation.

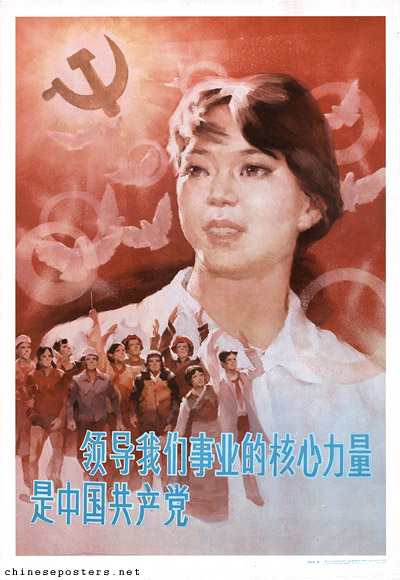

The Chinese Communist Party is the core force that guides our work, 1990

The CCP actively advertised the link between a love of China and loyalty to the Party. The official patriotism discourses highlighted the central role of the Party as the custodian of national interests. The message was quite clear: China would fall apart if the Party lost control of the country; only the CCP has the capacity to govern. From this perspective, political stability was only achievable through a single-party rule, and that became a prerequisite for a stronger and wealthier China in the future.

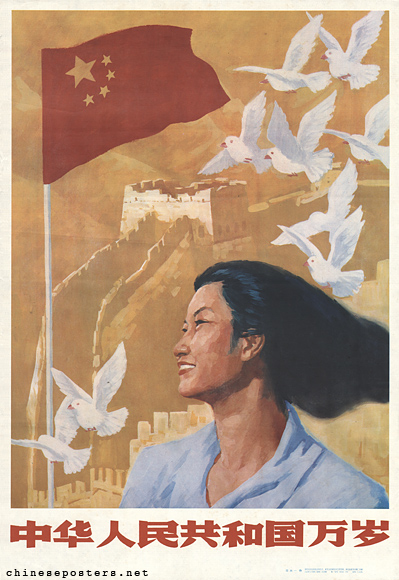

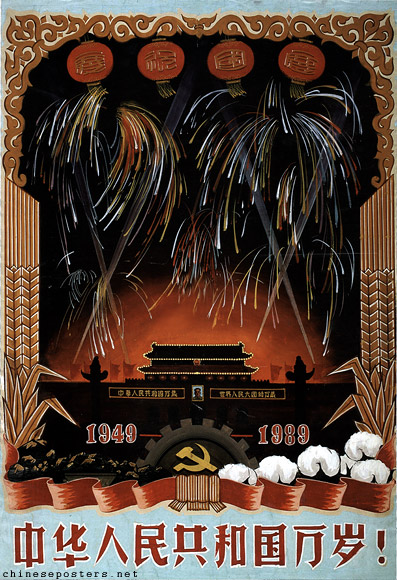

Long live the People's Republic of China, 1989

Patriotic education after 1989 generally encapsulated two themes: national pride, usually associated with prevailing national myths that emphasize honored achievements of the nation; and strong emotional feeling against national humiliations in the past, with a particular focus on the hardship that imperial Japan had inflicted upon the people during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Through school curricula, museum exhibits, and a wide range of media products such as books, TV programmes, computer games, maps, and paraphernalia, the CCP reminds its citizens to "never forget" the atrocities of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and to view modern Chinese history through the lens of "national humiliation". This strategy has been part of the Party’s ongoing attempt to construct a "pragmatic nationalism" that is meant to legitimate its rule in the postsocialist era.

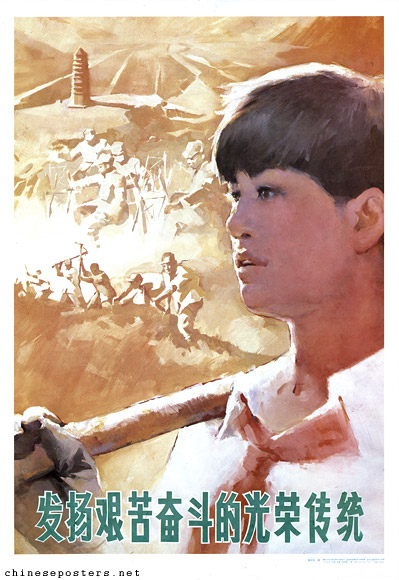

Establish the glorious tradition of bitter struggle, 1990

As a practical part of this campaign, students were forced to undergo military training, initially for one year, after the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations. The authorities considered such training both a political re-education device and a means of forestalling further unrest. In September 1989, all first-year students at Beijing and Shanghai Fudan Universities, institutions that had played a pivotal role in the uprising, had to receive a year's military training. In September 1990, this scheme was extended to most other universities and colleges. At that time, military training was compulsory for those wanting to go to college, and it is believed that students who refused were expelled from university. Compulsory military training was much critised by college authorities. Many students apparently went to colleges that were below their educational standard, but where they did not have to receive military training. In 1993, the length of military training for students was therefore reduced from a year to a month. This practice continues until the present.

Long live the People's Republic of China!, 1989

As for poster production and design, many of the posters aimed at younger Chinese (primary, secondary and higher school students) focus on loving the nation (= the Party), or the Party explicitly. The late 00's, with the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the PRC (2009), and the opening of the Shanghai World Expo (2010), offered ample themes for pushing the new patriotism.

60th Anniversary celebrations big military parade 1949-2009, 2009

Haiyan Lee, "The Ruins of Yuanmingyuan: Or, How to Enjoy a National Wound", Modern China 35:2 (2009), 155-190

Chuyu Liu & Xiao Ma, "Popular Threats and Nationalistic Propaganda: Political Logic of China’s Patriotic Campaign", Security Studies (2018), 1-32

Orna Naftali, "‘These War Dramas are like Cartoons’: Education, Media Consumption, and Chinese Youth Attitudes Towards Japan", Journal of Contemporary China 27:113 (2018), 703-718, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1458058

Florian Schneider, "China’s ‘info-web’: How Beijing governs online political communication about Japan", new media & society (2015), 1-21, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815600379

Mo Tian, "The Legacy of the Second Sino-Japanese War in the People’s Republic of China: Mapping the Official Discourses of Memory", The Asia Pacific Journal 20:11:4 (2022)

Edward Vickers, "Selling ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ -- ‘Thought and Politics’ and the legitimisation of China’s developmental strategy", International Journal of Educational Development 29 (2009), 523-531

Zheng Wang, "National Humiliation, History Education, and the Politics of Historical Memory: Patriotic Education Campaign in China", International Studies Quarterly 52 (2008), 783–806

Zhao, Suisheng. ‘‘A State-led Nationalism: The Patriotic Education Campaign in Post-Tiananmen China.’’ Communist and Post-Communist Studies 31:3 (1998), 287–302.