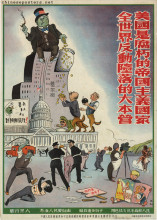

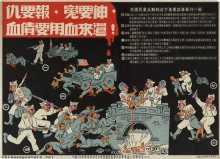

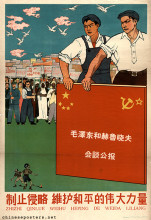

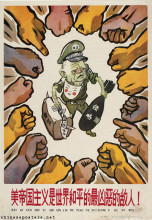

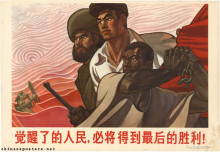

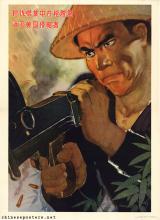

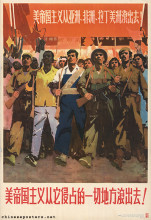

The fate of aggressors, ca. 1952

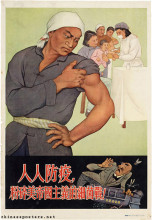

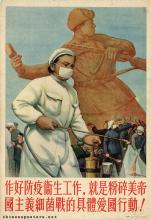

After the start of the Korean conflict, the United States officially became China's main foreign adversary. The war provided numerous opportunities to show Americans in an extremely unfavorable light. A recurring theme at the time was the accusation that America engaged in bacteriological warfare against China. Starting in 1952, this alledgedly included airdrops of contaminated or disease-carrying rats, insects and other vermin on Chinese soil. As a result, mass inoculation campaigns were organized, in concert with Patriotic Hygiene Campaigns to combat unhygienic conditions in urban and rural areas, and to annihilate potential disease-spreading animals and insects.

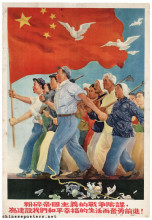

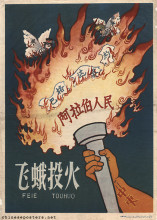

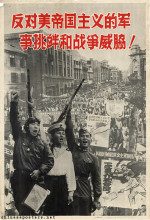

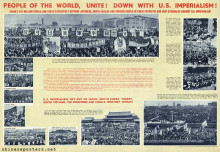

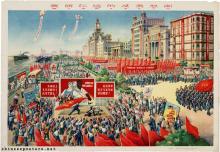

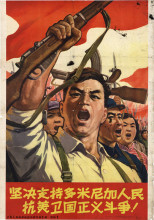

Oppose the military provocations and threats of war of American imperialism!, 1958

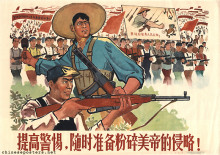

When the Sino-Soviet split had become unavoidable in the late 1950s, China virtually had no allies left in the international community. It felt threatened in the North by the military forces of the Soviet Union, which were amassed along the shared Northeastern border, and in the South by the growing military presence of the United States in Southeast Asia. Due to an actual territorial border conflict with the Soviets in 1969 over Zhenbao, or Damanski, Island, which later turned out to have been engineered by the Chinese themselves, the most explicit propaganda about China's fighting resolve henceforth was directed against the Soviet Union.

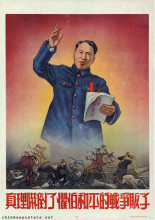

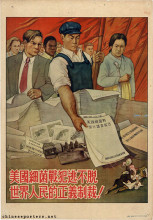

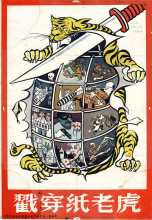

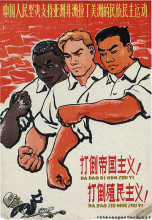

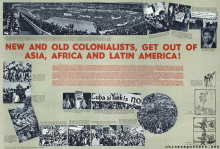

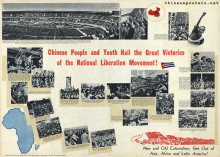

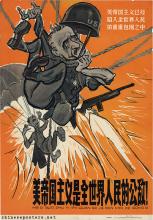

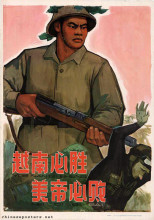

During the initial phase of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1969), China embarked on a crusade against both Soviet revisionism and American imperialism. Other reactionary forces elsewhere in the world remained unnamed, but were combatted with equal vehemence as paper tigers, with or without relevant quotes from Mao Zedong Thought.

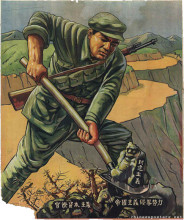

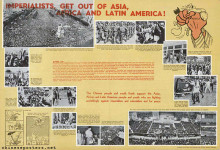

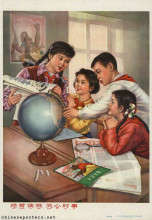

Propaganda directed to the foreign enemy at the front line teaching materials, early 1970s

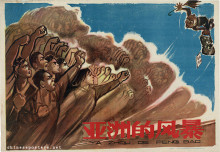

Imperialism and all reactionaries are all paper tigers, 1965

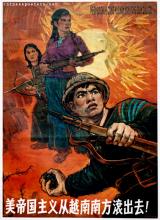

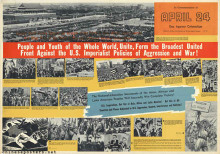

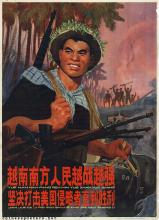

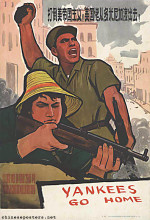

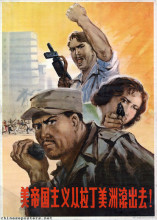

At the same time, protests against the American presence in Vietnam were recurring themes, accompanied by posters that showed the Chinese helping not only the Vietnamese but other Southeast Asian peoples as well.

Give prominence to politics, temper the skills, attack the aggressors, 1965

After the normalization of relations with the US in 1972, China ended its more extreme anti-American propaganda. The struggle against the Soviet Union, which was now accused of "socialist imperialism", continued. Only in 1989, relations with Moscow were normalized again.

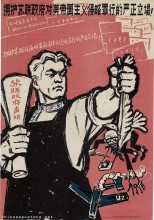

Imperialism and all reactionary forces are paper tigers, 1971

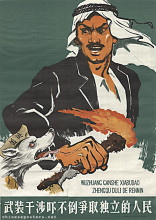

The relations with Japan were influenced negatively by the Chinese experiences during the Second World War. Fears continued to exist that Japan would see a revival of military aggression against China, no doubt supported by its close strategic ties with the US. The poster below, published in 1971, testifies to those fears. Nonetheless, in 1972, Sino-Japanese relations were normalized, including Japanese promises to compensate China for WWII, and a Japanese commitment to oppose (Soviet) hegemonism. Only after 1991, anti-Japanese feelings in China were vented again, leading to some spectacular outpourings of popular antipathy, as in Spring 2005.

Down with the revival of Japanese militarism, 1971

Rana Mitter, "Old Ghosts, New Memories: China's Changing War History in the Era of Post-Mao Politics", Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 38, no. 1 (2003), pp. 117-131

Ruth Rogaski, "Nature, Annihilation, and Modernity: China's Korean War Germ-Warfare Experience Reconsidered", Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 61, no. 2 (May 2002), pp. 381-415

Nianqun Yang, "Disease Prevention, Social Mobilization and Spatial Politics: The Anti Germ-Warfare Incident of 1952 and the 'Patriotic Health Campaign'", The Chinese Historical Review, vol. 11, no. 2 (Fall 2004), pp. 155-182

Sino-Soviet Relations  , National Intelligence Estimate Number 100-3-60 (9 August 1960), declassified by the CIA in October 2004

, National Intelligence Estimate Number 100-3-60 (9 August 1960), declassified by the CIA in October 2004