Hu Feng (胡风, 1903-1985) was born into a worker’s family in Yidu, Hubei Province. He joined the Communist Youth League in 1923 while attending school in Nanjing. In 1928, he went to Japan, where he earned his upkeep by writing political essays. As a result of his leftist activities, he was expelled from Japan in 1933. Upon his return, he joined the League of Left-Wing Writers, which had been founded by Lu Xun. Although considering himself a Marxist, he opposed the Communist theory adhered to at the time, that literature had to reflect class struggle; he found an opponent in Zhou Yang, who would later rise to become the ‘culture czar’ in the People’s Republic. In the following years, Hu continued to express his resistance to what he saw as the doctrinairism in communist literary circles in various articles. It should be no suprise that he did not subscribe to Mao Zedong’s "Talks on Literature and Art", which were held at Yan’an in 1942, and in which literature (and art) were defined as political instruments. Despite Hu’s continued clashes with the official ideology, and with Zhou Yang, he embarked on a modest administrative career in literary circles after the founding of the PRC.

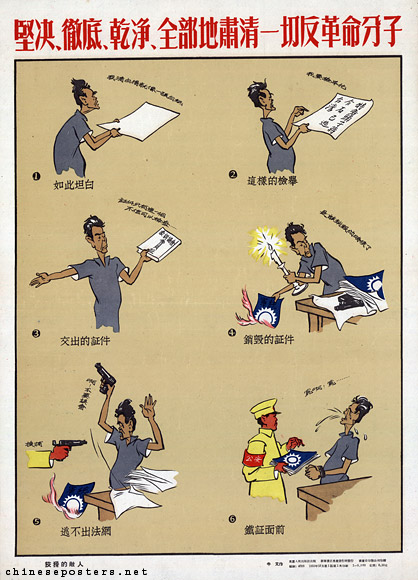

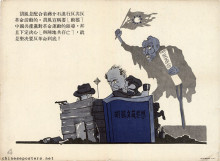

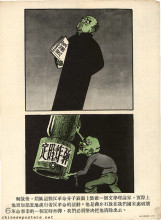

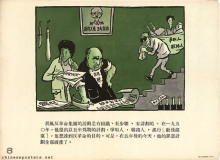

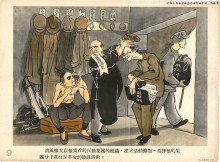

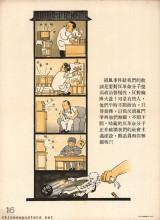

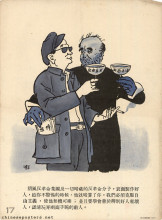

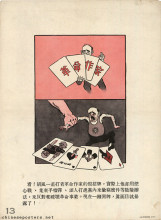

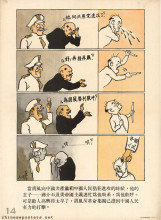

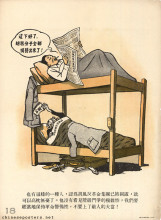

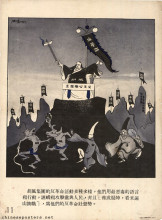

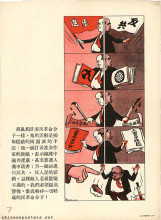

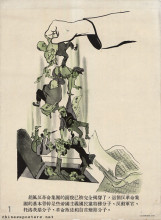

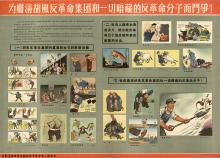

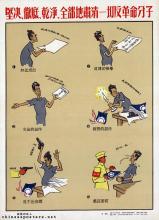

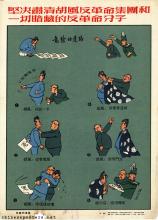

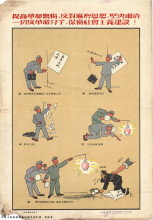

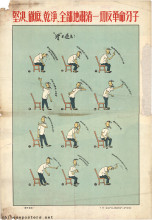

Resolutely, thoroughly, cleanly, completely eliminate all counterrevolutionary elements, 1955

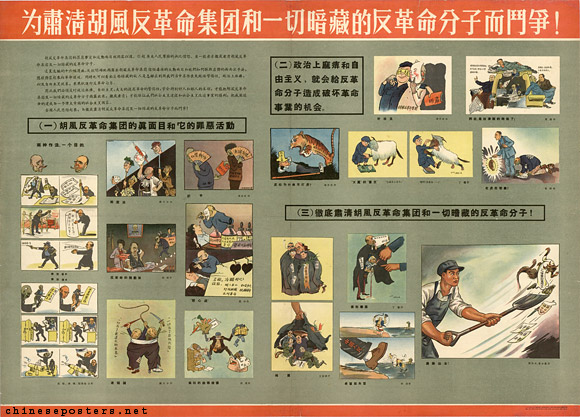

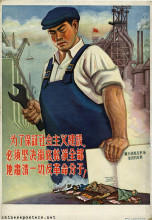

In 1955, Zhou Yang directed a campaign aimed at liquidating Hu and his followers, after the latter continued to express his opposition to what he saw as the sterile literature policy of the Party. This time, he was no longer regarded as a "deviationist guilty of subjectivism, emotionalism and aestheticism", but as a counter-revolutionary leader. The campaign against Hu Feng’s counter-revolutionary clique evolved into a reign of terror, and increased the estrangement between the Party and the intellectuals. Hu was deprived of all his posts and sentenced to 14 years imprisonment in the same year, to be served first in Qincheng prison, later in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. The Hundred Flowers movement (1956-1957) was in part a response to the demoralization among intellectuals, who subscribed to Hu’s views protesting totalitarian control of intellectual and artistic activity.

At the height of the Cultural Revolution, in 1969, Lin Biao and the Gang of Four changed his sentence into life imprisonment without appeal. Hu, who became mentally ill in prison, was only rehabilitated and released in 1980, and subsequently resumed his activities in the literary world until his death.

Wolfgang Bartke, Who was Who in the People’s Republic of China (München: K.G. Sauer, 1997)

Wolfgang Bartke, Biographical Dictionary and Analysis of China’s Party Leadership 1922-1988 (München: K.G. Sauer, 1990)

Donald W. Klein & Anne B. Clark, Biographic Dictionary of Chinese Communism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971)

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press 1995)

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao - The Memoirs of Mao’s Personal Physician (London: Random House, 1996)

Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Volume I: Contradictions Among the People, 1956-1957 (New York: Columbia University Press 1987)

Roderick MacFarquhar, Timothy Cheek, Eugene Wu (eds), The Secret Speeches of Chairman Mao - From the Hundred Flowers to the Great Leap Forward (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989)

S. Louisa Wei, Storm under the Sun: Introductions, Script, Reviews (Hong Kong: Blue Queen Cultural Communication Ltd., 2009)