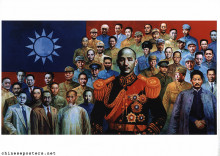

Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek), late 1990s

Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi, 蒋介石, 1887-1975) was born to a family that had long worked in the salt trade in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province. Like many of his class, generation and background, he went to Japan to study military science during the last years of the Qing Dynasty; while in Japan (1908), he joined the Tongmenghui (National Alliance, predecessor of the Guomindang) of Sun Yat-sen. He returned to China in 1911, where he saw action. There, he worked on various assignments for Sun. His military and political advance started after 1922. Sun appointed him Chief of Staff. In August 1923, he went to Moscow to study military affairs and obtain arms. After his return to Canton (Guangzhou) in 1924, he was appointed to the Military Commission of the Guomindang and made head of a committee to establish the Whampoa (Huangpu) Military Academy. By mid-1925, Chiang had become the key military figure in the GMD. When Sun had died in March 1925, his succession had not been decided upon yet; Chiang's military power and his role in the Northern Expedition (1926-1927), setting out to unite China and vanquish the warlords, strenghtened his hand. For this Northern Expedition, he was forced to collaborate with the communists in the so-called First United Front. With strong support from Comintern advisers and the communist faction within the GMD, Chiang was elected to the GMD Central Executive Committee in 1926. Soon, Chiang turned against the communists, culminating in the Shanghai Massacre in April 1927. Although Chiang was forced to step back, he returned by October 1928 as Chairman of the National Government established by the GMD in Nanjing in 1927; he effectively remained in supreme control of the GMD until his death.

Dress parade for Generalissimo Jiang, ca. 1938

At a Christmas party at Sun Yat-sen’s residence in 1921, Chiang met Song Meiling (1898-2003), the younger sister of Sun’s wife Song Qingling, and fell in love. After converting to Christianity, he received the family’s blessing to marry Meiling in 1927. Meiling became the fourth woman in Chiang's life, after Mao Fumei (毛福梅, 1882-1939), with whom he had an arranged marriage (1901); Yao Yecheng (姚冶誠, 1887-1966), his concubine (1912); and Chen Jieru (陳潔如, 1906-1971) (married in 1921). Chiang and Mao had a son, Chiang Ching-kuo; he and Yao adopted a son, Chiang Wei-kuo.

During the Nanjing Decade (1927-1937), Chiang sought to legitimize his leadership of the GMD and the country by presenting himself as both a leader of the Republican revolution and a personification of Chinese history and culture. He consciously used Confucian precepts of piety and loyalty to inspire respect, and presented himself as a “pater familias” of the Chinese nation. Chiang attempted to reinvent himself as a faithful disciple of Sun Yat-sen, working his public image into state-sponsored deification of Sun and the construction and consecration of sites in the landscape associated with the Republic’s founder. The new Republican capital also came to be widely associated with its massive Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, a site that Chiang consecrated amongst much fanfare in 1929. Chiang oversaw a modest programme of reform but the government's resources were focused on fighting internal opponents, including the Communists. To this end, the Nationalists organized so-called encirclement campaign (late 1920s-mid 1930s) with the goal of isolating and destroying the developing Chinese Red Army. The Nationalist forces launched four largely unsuccessful encirclement campaigns against Communist base areas in several separate locations across China. Only the fifth one, in 1934, was effective in the sense that it forced the CCP out of its Jiangxi Soviet and to escape on the Long March, ending in Yan'an.

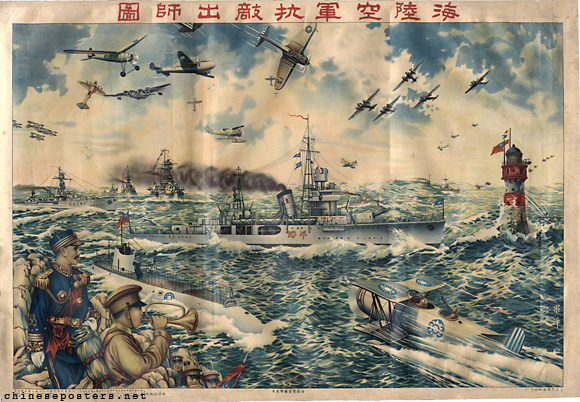

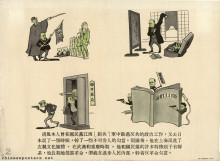

Picture of the Navy, Army and Air Force fighting against the enemy, ca. 1938

From 1931, Chiang also had to contend with a Japanese invasion in Manchuria. Chiang was forced to choose where to allocate his forces, and he chose the communists over fighting Japanese aggression. His "first internal pacification, then external resistance" was widely unpopular. Zhang Xueliang, a patriotic warlord in the western city of Xi'an took issue with Chiang’s policy and decided to take matters into his own hands. Zhang, together with General Yang Hucheng, kidnapped Chiang, refusing to release him unless he resumed cooperation with the Communists under a Second United Front in order to deal with the Japanese aggression. After releasing Chiang and returning to Nanjing with him, Zhang was placed under house arrest and the generals who had assisted him were executed. Chiang's commitment to the Second United Front was nominal at best, and it was all but broken up in 1941.

In 1934, Chiang and his wife launched the New Life Movement, a government-led civic campaign to promote cultural reform and Neo-Confucian social morality (as part of an anti-Communist campaign) and to ultimately unite China under a centralised ideology. The movement advocated a life guided by four virtues, li (禮/礼, proper rite), yi (義/义, righteousness or justice), lian (廉, honesty and cleanness) and chi (恥/耻, shame; sense of right and wrong). Chiang later extended the four virtues to eight by the addition of “Promptness”, “Precision,” “Harmoniousness,” and “Dignity”. These elements were summarized in two basic forms: “cleanliness” and “discipline” and were viewed as the first step in achieving a “new life”. People were encouraged to engage in modern polite behaviour, such as not to spit, urinate or sneeze in public. They were encouraged to adopt good table manners such as not making noises when eating; these concerns very muched echoed Sun Yat-sen's sentiments regarding the deficiencies of the Chinese people. The New Life Movement thus aimed to control Chinese lifestyles: opposition to littering and spitting at random; opposition to opium use; opposition to conspicuous consumption; rejection of immoral entertainment in favour of artistic and athletic pursuits; courteous behaviour; saluting the flag. Chiang urged citizens to bathe with cold water, since the (supposed) Japanese habit of washing their faces with cold water was a sign of their military strength. Yet, the Movement's inability to formulate a systematic ideology and abstract code of ethics contrasted sharply with the promises of the Communists, who spoke sharply and to the point on taxation, distribution of land and the disposition of overlords.

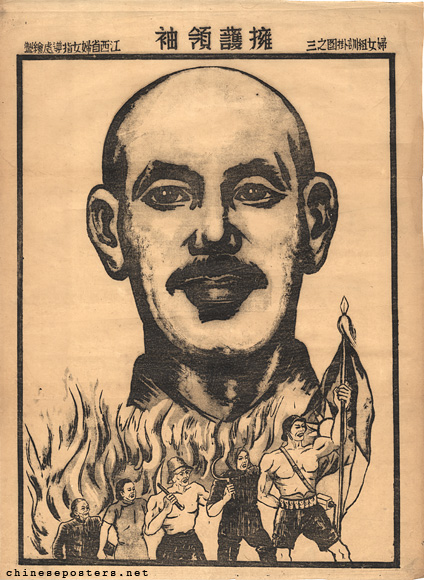

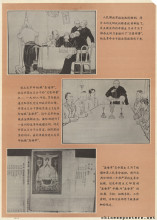

Support the leader -- Women's Group Training Wall Chart Nr. 3, ca. 1939

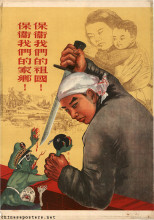

In 1937, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China. In late 1937, they reached the capital in Nanjing. The Chinese attempted to resist, holding their ground for several weeks, but eventually were forced to flee. The Japanese army committed atrocities across northern China, raping and pillaging as they moved south, culminating in the Rape of Nanjing, in which hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians were massacred. Forced to flee to Chongqing by the Japanese advance, Chiang spent the next seven and a half years of the war ineffectively resisting the Japanese and worrying about the communists. Chiang received military aid from the British and Americans, and even had an American Chief of Staff, General “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell. Stilwell became increasingly frustrated with Chiang’s reluctance to commit troops to battle against the Japanese, suspecting that he was withholding his strength in order to be ready to resume fighting with the communists after an Allied victory.

When the United States entered the war against Japan in 1941, China became one of the Allied Powers. As Chiang's position within China weakened, his status abroad grew and in November 1943, he travelled to Cairo to meet US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. His wife, Song Meiling, travelled with him and became famous in the west as Madame Chiang.

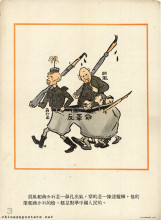

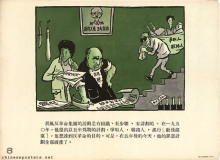

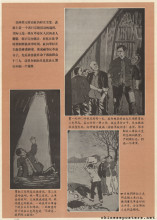

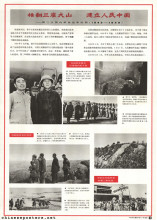

The destruction of the Jiang dynasty, 1978

As Chiang expected, the end of World War II led to the outbreak of open civil war in China. By that time his own army and his government had lost most credibility, and public support of the countryside allowed the Red Army to encircle and capture the cities. Any strength Chiang conserved during the war availed him little, as the communists sent the remnants of his government fleeing to Taiwan in 1949. There, Chiang established a government in exile, which he led for the next 25 years under a system of martial law (only to be lifted in 1987 by his son and successor, Chiang Ching-kuo). He died in 1975.

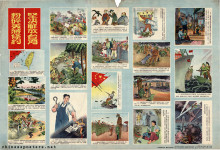

While in Taiwan, Chiang developed strategies to retake the mainland. In 1950, he vowed that the GMD would retake the mainland in five years: one year of preparations; attack in the second year; sweeping across China in year three and four; and successfully retaking all of the mainland in year five. After this five year period, there would be 10 years of growth. During two Taiwan Strait crises (in 1954-1955 and 1958), the PRC bombarded the Taiwan-held offshore islands of Jinmen and Mazu (Quemoy, Matsu); it became obvious that while the collaboration between the PRC and the Soviet Union was weakening, the United States --an essential player in this respect-- were increasingly reluctant to render overt support.

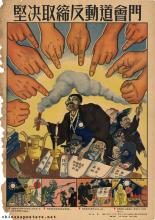

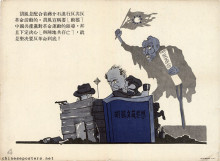

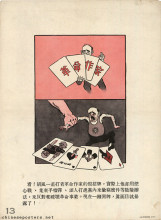

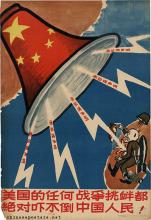

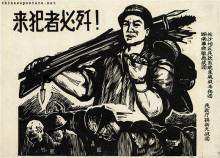

Liberate Taiwan, annihilate the remnants of the bandit Chiang Kai-shek, 1954

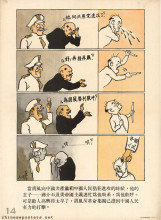

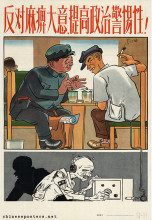

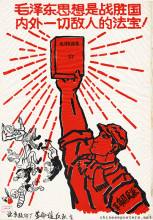

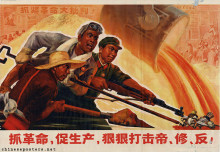

As Jeremy Taylor explains on his comprehensive website Enemy of the People -- Visual Depictions of Chiang Kai-shek, "Chiang was transformed on countless propaganda leaflets into the 'sick man of Asia', spindly and stunted [... He] was almost always presented in CCP poster art and textbooks as being far smaller than his detractors, and was contrasted not to Communist leaders, but to the towering, 'oversized' figures representing the Chinese masses, or specific groups therein, such as soldiers or peasants. Chiang cowered on a deserted Taiwan (signified most often by the inclusion of a palm tree), or waded through the waves to exile or a watery death. He appeared on the edge of such images, as if by being pushed off a poster he was also being expelled from history itself."

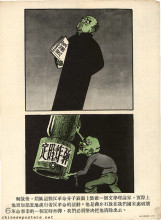

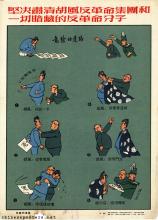

Looking for the road to death - let's break this open together, 1955

Only in the first decade of the 21st century, a reappraisal of Chiang Kai-shek and the Guomindang started to take place in what became known as "Republican Fever". This more positive attitude to Republican history was visible in academic studies and popular culture alike.

Arif Dirlik, "The Ideological Foundations of the New Life Movement: A Study in Counterrevolution", Journal of Asian Studies 34:4 (1975), 945-980

Federica Ferlanti, "The New Life Movement in Jiangxi Province, 1934–1938", Modern Asian Studies 44:5 (2010), 961-1000 doi:10.1017/S0026749X0999028X

Tony Saich, The Origins of the First United Front in China -- The Role of Sneevliet (alias Maring) (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1991)

Jeremy E. Taylor, "The Production of the Chiang Kai-shek Personality Cult, 1929–1975", The China Quarterly 2006, 96-110

Jeremy E. Taylor, Enemy of the People -- Visual Depictions of Chiang Kai-shek, The Digital Humanities Institute, University of Sheffield (https://www.dhi.ac.uk/chiangkaishek/)

Barbara Tuchman, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–45 (New York: Macmillan Publishers, 1971)

Peter Zarrow, China in War and Revolution 1895-1949 (London: Routledge, 2005)

Zhang Qiang & Robert Weatherly, "The rise of ‘Republican fever’ in the PRC and the implications for CCP legitimacy", China Information 27:3 (2013), 277-300 DOI: 10.1177/0920203X13500458