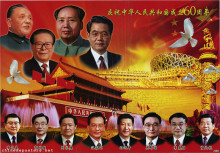

In the Yan’an era, the use of leader portraits for propaganda purposes was first put into practice. The genre, derived from Soviet practice and used from 1943 on, featured local, national and international figures, military and political leaders (Mao Zedong, amongst others), and labor and hygiene models. These pictures were sold, but they could also be awarded as prizes.

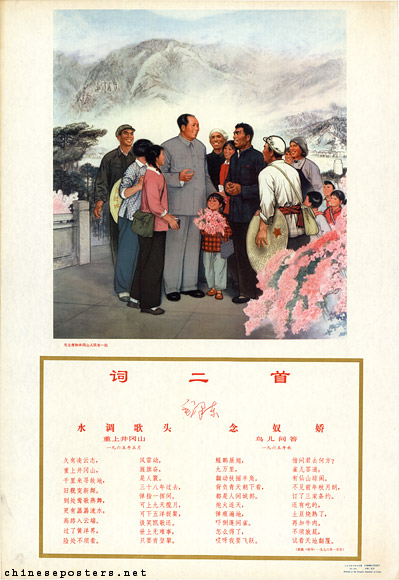

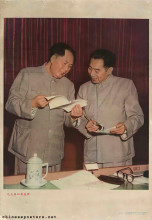

The Chairman comes to our home, he takes the trouble to make detailed inquiries while chatting, 1965

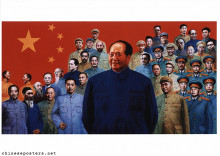

The attempts to create leader-worship, as with Mao Zedong since the late 1940s, reached a crescendo during the Cultural Revolution. After Hua Guofeng tried to fill Mao’s shoes by using the same visual idiom in the late 1970s, however, it disappeared completely in the 1980s.

Two poems (by Mao Zedong), early 1970s

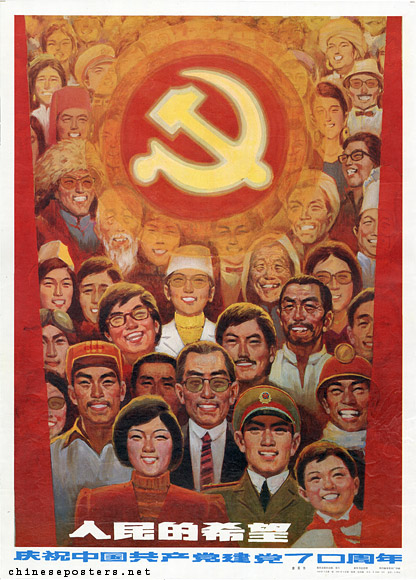

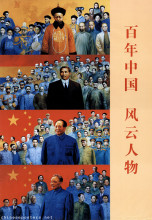

Instead, in line with Deng Xiaoping’s dictum that leaders and their glorious deeds should remain in the background, while at the same time trying to bolster the flagging support for the CCP, the stress was on subjects that portrayed the glorious deeds of the past. Posters concentrated on the formative, pre-1949 period, and on glorious, departed leaders, in particular Zhou Enlai. Only one or two posters therefore were published in the 1980s that showed the representatives of the leading group of the times, be they Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun, Hu Yaobang, or Zhao Ziyang.

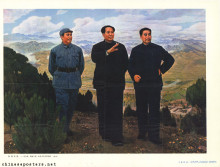

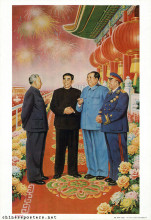

Comrades Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De, Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun together, 1982

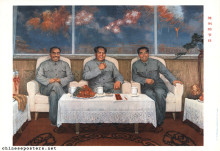

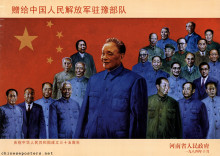

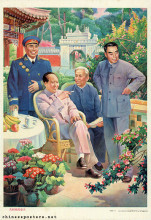

The older leaders, including Deng and Chen, however, did appear in posters that showed group photographs, or paintings, of the members of the CCP-leadership of the 1950s, including Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi and Zhu De. This was an obvious attempt to demonstrate the legitimacy of the Deng-line. In these posters, Deng and Chen are often given a higher profile and position than history would suggest. ‘Chairman Mao Zedong and his comrades-in-arms,’ is an artist’s impression of the well-known photograph of the reception of Zhou Enlai at Beijing airport in 1964, to which Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun (who were not present at the time) have been added.

Chairman Mao Zedong and his comrades-in-arms, 1983

Comrades Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi and Zhu De together, 1983

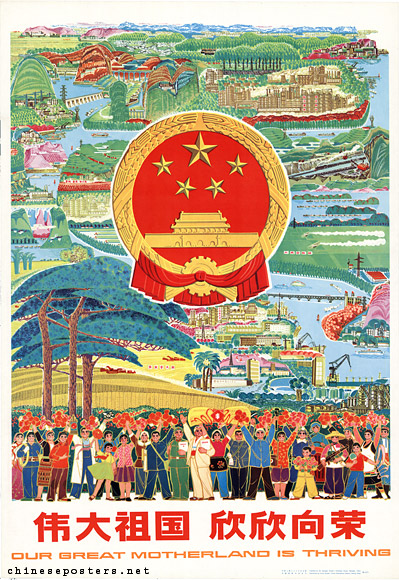

Deng Xiaoping decided to do away with the leader worship as it had been practised in the past. Before the Cultural Revolution started, he had been one of the few who criticized Mao for basking in the adoration of the masses. He himself succeeded in becoming a Chinese supreme leader who only rarely appeared on propaganda posters. The decision initially posed a problem for the visualization of political power, and therefore of the Party itself. Non-personalized symbolism was found in the emblem of the State (Tiananmen); the CCP’s logo of hammer and sickle; and the symbol of the nation (five yellow stars on a red background). The only exceptions to Deng’s veto on leader portraits were those featuring the leaders who had collaborated with Mao during the revolution. Of course, in selected places the image of Mao, whether in painted or sculpted form, remained to be used; Mao’s portrait overlooking Tiananmen Square is probably the best known example.

Our great motherland is thriving, early 1970s

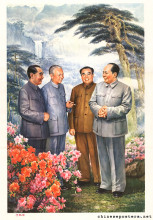

Only with Deng’s retirement from public life after the Tiananmen Incident in 1989, the Propaganda Department finally saw an opportunity to build up a cult around the "Chief Architect" of reform. In November 1992, after Deng had made an inspection tour of the most advanced and prosperous provinces in the South, a portrait of him was released as a poster, done in typical brushwork style. A year later, posters appeared that featured Deng’s more remarkable remarks ("We should do more, and engage in less empty talk", amongst others), against a backdrop of either a photo montage of a modern city skyline, or flower arrangements reminiscent of the 1950s.

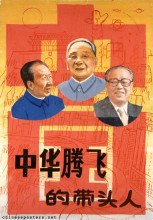

In a way which resembles the famous Mao Zedong/Hua Guofeng posters of 1976, Deng’s chosen successor Jiang Zemin appeared, together with his patron, in a poster released in 1992. With Deng’s demise in February 1997, the market was flooded with "Deng posters". It seems as if Deng, with his health declining, was unable to keep the Party propaganda machinery - and Jiang Zemin - from using him as a propaganda object.

Wen-Hsuan Tsai, "Framing the Funeral -- Death Rituals of Chinese Communist Party Leaders", The China Journal 77 (2016), 51-71

![[Mao, Deng, Jiang, Hu]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/2020-06/e17-283.jpg?itok=-B_Ep-ci)

![[Mao, Deng, Jiang, Hu]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/2020-06/l4-589.jpg?itok=2CvVsPz9)