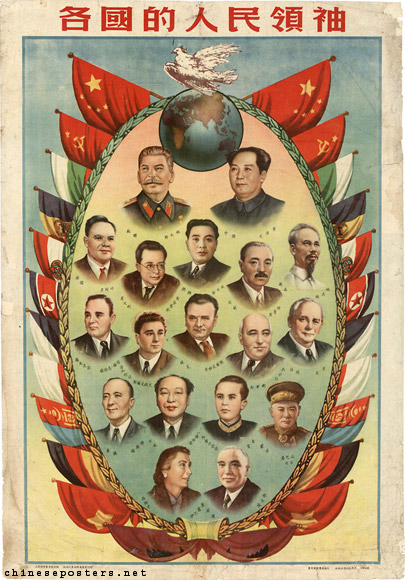

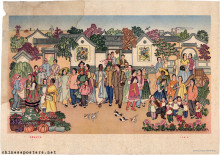

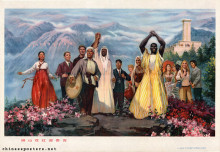

People’s leaders of all countries, ca. 1951

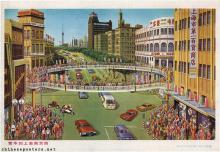

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic, an ever increasing number of countries and peoples have basked in the warm friendship of China. In the 1950s, however, when China still was wedded closely to the international socialist movement, only the Soviet Union and the socialist countries in Eastern Europe were considered close comrades.

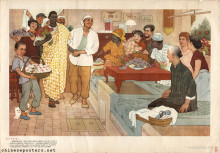

Long live the unity of the peaceful, democratic, socialist camp! 1958

As the years progressed, China increasingly felt stifled by the need to follow the Soviet Union’s foreign policy intitiatives. Peking felt proud of its revolutionary successes and wanted to play an international role more commensurate with its perceived status. In 1954, while on a visit to India, Zhou Enlai, accompanied by Chen Yi, unveiled the so-called ‘Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence’ (mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; mutual non-aggression; non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence) with which China defined its international position.

Premier Zhou on a visit to India, 1954

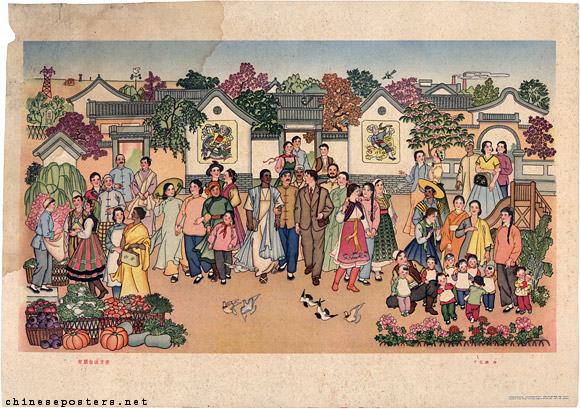

The non-aligned countries (former colonies and newly independent states) joined the ranks of China’s friends and allies after the Bandung Conference which took place in Indonesia in 1955. There, the ‘Five Principles’ were reaffirmed and incorporated in the ‘Ten Principles of the Bandung Conference’. After the Sino-Soviet split in the late 1950s, China sought relations with a larger number of countries than ever before. This trend was stemmed when the Cultural Revolution started in 1966.

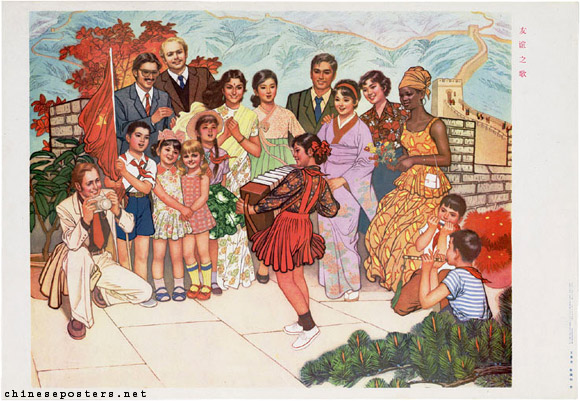

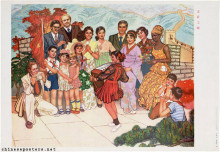

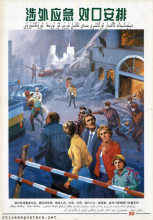

Friends from afar are coming to visit, 1961

The commune receives the honored guests, the sisters’ hearts are linked, 1964

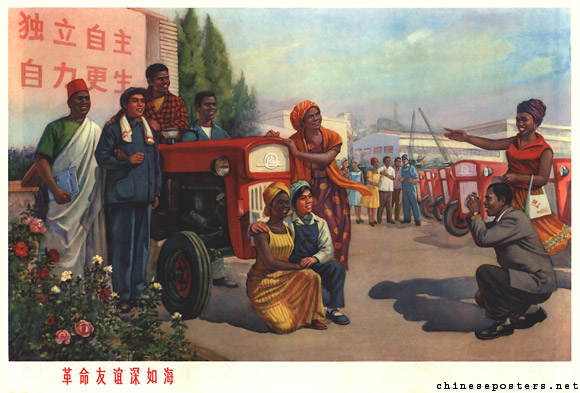

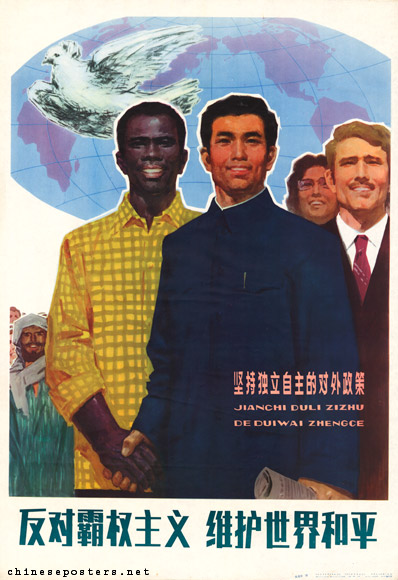

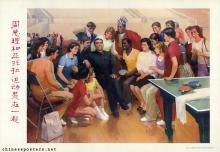

During the Cultural Revolution, foreign relations clearly were not the main concern of the Chinese leadership. This could be seen from the Red Guard attack on the British embassy and the siege of the Soviet embassy. Initially, all Chinese ambassadors were recalled, with the exception of Huang Hua, who was allowed to remain in Cairo, Egypt. While (American) imperialism and (Soviet) revisionism were criticised, solidarity with Indochina and Vietnam was promoted; close relations with Albania and Romania, countries that were openly critical of the Soviet Union, were lauded. Only representatives of friendly nations and political/revolutionary parties in Asia, Africa and Latin America - as well as ideological sympathisers from elsewhere - visited Peking during those heady days of continuous revolution.

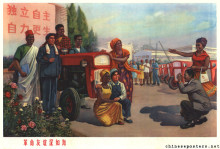

Revolutionary friendship is as deep as the ocean, 1975

Despite the large numbers of visitors arriving in China, expressing their support for what seemed like a relevant revolutionary model, China’s support usually remained confined to rethoric. Aside from some spectacular projects in support of the actual needs of developing nations - the famous TanZam Railway springs to mind - most of China’s assistance consisted of copies of Mao Thought, military training, or shipments of weapons.

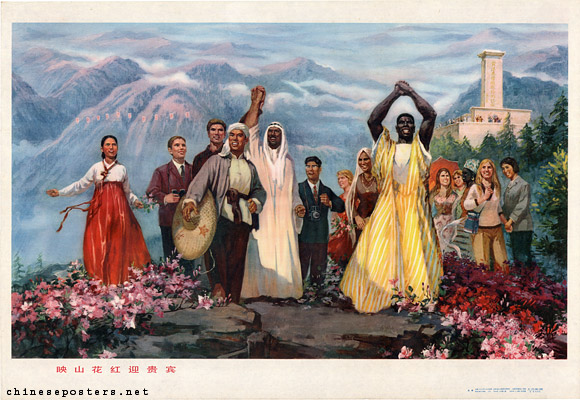

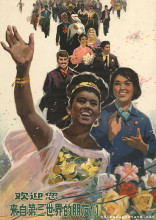

Azaleas welcome the honored guests, 1978

Once the relations with the United States improved (after President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972), the number of countries maintaining relations with the PRC increased significantly. This trend continued when Hua Guofeng started the Open Door policy in 1977, which was incorporated in the developmental "Four Modernizations" blueprint of Deng Xiaoping in 1978. Nowadays, only the ever decreasing number of countries that recognize (the Republic of China on) Taiwan does not maintain relations with China.

Although in the 00s talk about China’s "Peaceful Rise" or - less threatening - "Peaceful Development", colors most of the discussions on China’s position in the world, the ‘Five Principles’ basically remain in force as the doctrine undergirding China’s foreign policy. Many Chinese foreign policy experts are convinced that these Principles will attain international recognition and application once China has succeeded in changing the current unipolar world order into a multipolar, or even more preferably, bipolar one.

Arif Dirlik, "The Bandung legacy and the People's Republic of China in the perspective of global modernity", Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 16:4 (2015), 615-630

Emily Wilcox, "Performing Bandung: China’s dance diplomacy with India, Indonesia, and Burma, 1953–1962", Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 18:4 (2017), 518-539