Advance victoriously while following Chairman Mao’s revolutionary line, 1971

Lin Biao (林彪, 1907-1971) was considered one of the strategic men of genius of the Red Army and its successor, the People’s Liberation Army. The son of a small landlord, Lin joined the Communist youth corps in 1925, and studied at the Whampoa Military Academy, where he met Zhou Enlai. After the split between the Communist Party and the Guomindang and the abortive Nanchang Uprising (1927), Lin served under Zhu De. Together, they fought their way to Jinggangshan, where Lin first met Mao Zedong in 1928. Commanding the Red Army’s First Army Group, Lin defended the Jiangxi Soviet against Chiang Kai-shek’s Extermination Campaigns. During the Long March (1934-1935), Lin’s unit formed a vanguard. While crossing the Dadu River, Lin was responsible for capturing the Luding Bridge, a truly heroic feat. In Yan’an, Lin headed the Worker-Peasant Red Army University. During an engagement with Japanese troops, he was wounded. He received medical treatment in Moscow during the years 1938-1942.

Long live the proletarian headquarters led by Chairman Mao and assisted by vice-Chairman Lin, 1969

After his return to Yan’an, Lin was involved in troop training and indoctrination assignments. His strategic prowess came again to the fore during the civil war (1946-1949). He was responsible for defeating the Guomindang armies in Manchuria, and for taking both Peking and Tianjin. Sweeping further southward, Lin occupied Hainan Island by October 1949. Following this, he was installed as Commander of the Central China Military Region. His activities in the following years are unclear. Presumably, he suffered from both mental and physical health problems. As a result, he did not lead his troops in the Korean War that started in 1950. In 1955, he was made a Marshal of the People’s Liberation Army, and in 1958, he had become Vice-Chairman of the Party Central Committee. After the Lushan Plenum in 1959, Lin replaced Peng Dehuai as Minister of Defense. Subsequently, he (or those surrounding him, including his wife Ye Qun and son Lin Liguo) began plotting to become Mao’s chosen successor.

Lin’s strategic thinking, encapsulated in the so-called ‘Four Firsts’ program that put men over weapons; political over other work; ideological over routine work; and ‘practical thought’ over book-learning, very much coincided with Mao’s newly discovered penchant for self-sacrifice and self-sufficiency, qualities that were called for after the disastrous Great Leap Forward campaign. To further ingratiate himself with Mao, Lin fanned the personality cult around the Great Helmsman. He made the Army a great school of Mao Zedong Thought, and had Mao’s Quotations compiled and published in the famous Little Red Book, for which he wrote an inscription and a fawning introduction. Moreover, he supported Jiang Qing and her attempts to play a significant role in Chinese politics with her supporters, united in the Gang of Four.

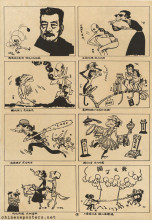

Denounce the heinous crimes of the renegade and traitor Lin Biao!, 1973

After having been annointed Mao’s "close comrade in arms" and designated successor in 1969, Mao seemed to turn against Lin and his supporters. In an attempt to take over power from Mao, Lin and his faction allegedly drew up a plan for a coup, or armed uprising, the Wu qi yi (571, a pun on ‘armed uprising’) plan. Before it could be implemented, Mao, Zhou Enlai and others found out. Fleeing the country with his family and staunch supporters, Lin’s plane crashed over the former Mongolian People’s Republic in 1971. It would take another year before this information was made known to the Chinese population. Lin’s ‘betrayal’ was severely criticized in the Gang-of-Four-inspired "Campaign to Criticize Lin Biao and Confucius", which started in 1974.

After having been annointed Mao’s "close comrade in arms" and designated successor in 1969, Mao seemed to turn against Lin and his supporters. In an attempt to take over power from Mao, Lin and his faction allegedly drew up a plan for a coup, or armed uprising, the Wu qi yi (571, a pun on ‘armed uprising’) plan. Before it could be implemented, Mao, Zhou Enlai and others found out. Fleeing the country with his family and staunch supporters, Lin’s plane crashed over the former Mongolian People’s Republic in 1971. It would take another year before this information was made known to the Chinese population. Lin’s ‘betrayal’ was severely criticized in the Gang-of-Four-inspired "Campaign to Criticize Lin Biao and Confucius", which started in 1974.

After decades of invisibility, Lin Biao reappeared on a 2003 poster, commemorating the foundation of the People’s Liberation Army.

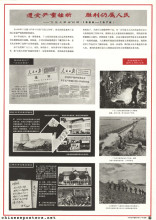

A Great Trial in Chinese History - The Trial of the Lin Biao and Jiang Qing Counter-Revolutionary Cliques, Nov. 1980-Jan. 1981 (Peking: New World Press, 1981)

Chen Yu (ed.), Zhonghua renmin gongheguo 36 junshijia [36 Strategists of the People’s Republic of China] (Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe, 2002) [in Chinese]

Dachang Cong, When Heroes Pass Away - The Invention of a Chinese Communist Pantheon (Lanham MD: University Press of America, 1997)

Martin Ebon, Lin Piao - The Life and Writings of China’s New Ruler (New York: Stein and Day Publishers, 1970)

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Li Rui, Lushan huiyi shilu [True Record of the Lushan Plenum] (Peking: Chunqiu chubanshe/Hunan jiaoyu chubanshe, 1989) [in Chinese]

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao - The Memoirs of Mao’s Personal Physician (London: Random House, 1996)

Liao Yiwen (ed), Tian Lun [Family Love and Friendship] (Tianjin: Tianjin jiaoyu chubanshe, 1995)

Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Volume II: The Great Leap Forward, 1958-1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987)

Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Volume III: The Coming of the Cataclysm (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999)

Helmut Martin, Cult & Canon - The Origins and Development of State Maoism (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 1982)

Frederick Teiwes and Warren Sun, The Tragedy of Lin Biao - Riding the Tiger During the Cultural Revolution 1966-1971 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1996)

Yan Jiaqi & Gao Gao (translated & edited by D.W.Y. Kwok), Turbulent Decade - A History of the Cultural Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1996)

Yang Kelin (ed.), Wenhua dageming bowuguan [Museum of the Cultural Revolution] (Hong Kong: Dongfang chubanshe youxian gongsi, Tiandi tushu youxian gongsi, 1995) [in Chinese]