Xi Jinping (习近平, 1953) follows in the footsteps of Mao Zedong, Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao as the sixth generation of leaders of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In contrast with his immediate predecessors Deng, Jiang and Hu, who took pains to project a style of collective leadership, Xi has been actively engaged with concentrating power in his hands. As the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the President of the PRC and the Commander-in-Chief of the People’s Liberation Army, his authority is now considered to be as encompassing as Mao’s was. Many observers, both within and without China, see him as a new Mao. This is further bolstered by the fact that at the 19th Party Congress that convened in 2017, he has been able to do away with the constitutional two-term limit of five years that was introduced under Deng: Xi is the leader for life, as Mao was. Moreover, he has taken over as the head of key party leading groups dealing with economic, financial, and international affairs. As the ‘core’ of the party leadership (since 2016), Xi has effectively become the ‘chairman of everything’.

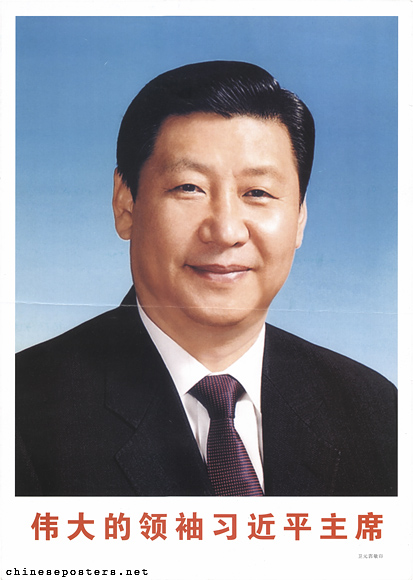

Great leader chairman Xi Jinping, ca. 2014

Xi is the son of Xi Zhongxun (习仲勋, 1913-2002), who joined the CCP in 1928 and took part in creating the revolutionary base area of Yan’an before the CCP arrived in 1935. In the early 1950s, the elder Xi became one of the youngest cabinet ministers, responsible for propaganda. As a result of his alignment with Gao Gang (高岗), the purged Vice-Chairman, Xi saw his career sidetracked; in 1962, he was purged himself. His father’s questionable political credentials made it impossible for the younger Xi to join the Red Guards when the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) broke out, and he suffered for his father’s alleged misdeeds. He was exiled to Liangjiahe (两家和), a village near Yan’an, in 1969. According to some villagers, he was too weak for agricultural work and could not stomach the coarse food; according to other sources, Xi tried to run away in August 1969, only to be arrested by police in Beijing and returned a year later. Xi himself has admitted to have been locked up a few times. Nonetheless, he took to living in the countryside, an episode that now features prominently in his official biography as part of his formative experience. In 1974, after many rejections because of his father’s political problems, he became a full member of the CCP and the party secretary of the production brigade of the village.

Carry forward the cause and forge ahead into the future, 2012

In 1975, Xi was allowed to return to Beijing. He entered Tsinghua University as a worker-peasant-soldier student, on the basis of nominations from local cadres. In 1978, the elder Xi was rehabilitated and sent to run Guangdong province. Due to the father’s new position and influence, the younger Xi got a job in the secretariat of the Central Military Commission, where he built up a network of generals that he has cultivated to this day. In 1983, Xi left the Beijing bureaucracy and began his rise through the provinces, starting as a deputy secretary in Zhending, a lowly county in Hebei Province. In 1985, he transferred to Fujian Province to eventually become governor (in 1999), and in 2002, he headed the economically vibrant Zhejiang Province. His activities on the national stage became visible in 2007, when he was called in to clean up a corruption scandal in Shanghai that implicated associates of Jiang Zemin. That same year, after joining the Standing Committee of the CCP Politbureau, he was identified as the new leader of China. By the time Hu Jintao was set to step back, Xi was faced with an extraordinary challenge from Bo Xilai (薄熙来), a leader with a similar pedigree of being a Red Princeling (and comparable behind-the-scenes support). Bo and his wife Gu Kailai would become implicated in the murder of a Western business man and end up in prison. Xi prevailed over Bo, and became the new CCP General Secretary on 15 November 2012.

Policies

Xi’s pre-eminence is illustrated by the 2017 inclusion of his theoretical contributions, also known as ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’, in the CCP Constitution.

Completely settle the question of corruption, flies as well as tigers must be struck, 2014

The Xi era is marked by a number of high-profile policies, both domestic and international. A domestic policy that has met great support (and trepidation) is the anti-corruption campaign that was started in 2012 under the auspices of Wang Qishan (王岐山), a key supporter of Xi’s. It has netted hundreds of thousands of ‘flies’ (small-time embezzlers and low-level administrators) and ‘tigers’ (high level officials in the civilian and military sectors). As many of those who have ‘fallen off their horses’ had been opponents of Xi, the campaign is seen as a way for Xi to get rid of threats to his rule. The ‘Chinese Dream’ policy, aiming to rejuvenate the nation and to make China strong and powerful again, has found domestic resonance among those who want China to stand up and be counted again for what it is: the greatest nation in the world.

With one heart to build the Chinese Dream together, ca. 2013

Internationally, this Chinese Dream is to be realized through the policy of ‘One Belt, One Road’ (yi dai yi lu, 一带一路) that was unveiled in 2013. It is made up of two components: the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’, which aims to bring together China, Central Asia, Russia and Europe (the Baltic), link China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and West Asia, and connect China with Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean; and the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’, the sea connection that will link China’s coast to Europe through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean in one route, and from China’s coast through the South China Sea to the South Pacific in the other. It is now known as the Belt-Road Initiative.

Private life

The Chinese dream, the dream of a strong nation, ca. 2016

Xi was married to Ke Xiaoming, the daughter of a Chinese diplomat, but the marriage was dissolved when Ms. Ke wanted to move to the UK. He then married Peng Liyuan (彭丽媛) in 1987. Ms. Peng (1962), a former member of the People’s Liberation Army Song and Dance Troupe, is a celebrity soprano who performed for the troops as well as at the annual televised New Year extravaganzas before her marriage. Wildly popular for her patriotic folk songs, she initially was better known, and more popular, than her husband. They have one daughter, Xi Mingze (1992), who studied psychology and English at Harvard University and graduated in 2015.

Jessica Batke & Mareike Ohlberg, "Branding Xi – How the CCP creates a professional PR leadership package for the modern era", MERICS Web Special, Mercator Institute for China Studies, August 2016

Ane Bislev, "The Chinese Dream: Imagining China", Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences (2015) 8, 585-595

Benjamin Carlson, "The World According to Xi Jinping", The Atlantic 21 September 2015

China Civilization Office, CCP Central Propaganda Department, Jiang wenming shu xinfeng gongyi guanggao (Practice culture, establish a new practice public service advertisements) (2013)

Ashley Esarey, "Propaganda as a Lens for Assessing Xi Jinping’s Leadership", Journal of Contemporary China 30:132 (2021), 888-901

Stefan R. Landsberger, "Dreaming the Chinese Dream - How the People’s Republic of China Moved from Revolutionary Goals to Global Ambitions", International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity, 2:3 (2014), 245-274

Chunlong Lu, "Urban Chinese Support for the Chinese Dream: Empirical Findings from Seventeen Cities", Journal of Chinese Political Science (2015) 20, 143–161

Evan Osnos, "Born Red", The New Yorker, 6 April 2015

Tony Saich, What Does General Secretary Xi Jinping Dream About?, Ash Center Occasional Papers, Harvard Kennedy School, August 2017

Michael D. Swaine, "Chinese Views and Commentary on the ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiative", China Leadership Monitor 47 (2015), 1-24

Zhengxu Wang & Jinghan Zeng, "Xi Jinping: the game changer of Chinese elite politics?" Contemporary Politics 2016, 1-18

Suisheng Zhao, "From Affirmative to Assertive Patriots: Nationalism in Xi Jinping’s China", The Washington Quarterly 44:4 (2021), 141-161

![[Xi Jinping and Peng Liyuan]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/2020-06/e37-412.jpg?itok=QfjXh2XE)

![[Xi Jinping, warship, jet fighters]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/l4-611.jpg?itok=BNIiRG7T)