Guo Moruo (郭沫若, 1892-1978), formerly known as Guo Kaizhen (郭开贞), was born in Shawan, Leshan, Sichuan Province. He was a modern Chinese writer, historian, archaeologist and politician. His pen names include Mike Aung (麦克昂), Guo Dingtang (郭鼎堂), Shi Tuo (石沱), Gao Ruhong (高汝鸿), Yang Yizhi (羊易之), and others.

Guo Moruo (郭沫若, 1892-1978), formerly known as Guo Kaizhen (郭开贞), was born in Shawan, Leshan, Sichuan Province. He was a modern Chinese writer, historian, archaeologist and politician. His pen names include Mike Aung (麦克昂), Guo Dingtang (郭鼎堂), Shi Tuo (石沱), Gao Ruhong (高汝鸿), Yang Yizhi (羊易之), and others.

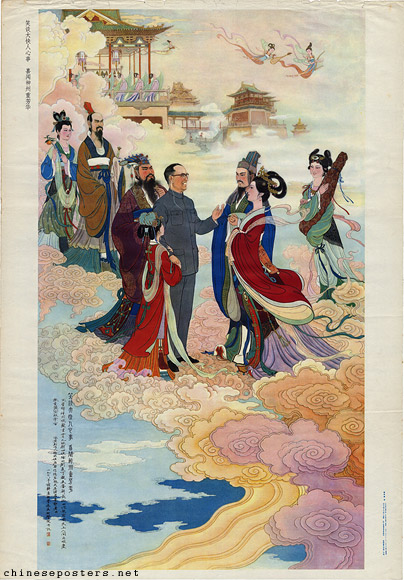

The son of a wealthy businessman in Sichuan, Guo became a troublemaker at school. In 1914 he followed his older brothers to Japan and started a de facto marriage with a Japanese woman (Sato Tomiko, 佐藤 富子), enrolling in medical school but being slowly seduced by Western literature. In 1919, he threw himself into the May Fourth Movement, translating and comparing himself to Goethe, and writing poems such as "Embracing a Baby and Bathing in Hakata Bay" (抱和儿浴博多湾中) and "Phoenix Nirvana" (凤凰涅槃). In August 1921, the collection of poems "The Goddesses" (女神), the first significant collection of poetry in vernacular Chinese was published. In 1923, he completed the historical drama "Zhuo Wenjun" (卓文君) and the collection of poems, operas and essays "Starry Sky" (星空).

Guo officially converted to Marxism in 1924, and his attitude soon shifted against foreigners. After the “May 30th Incident”, where foreign police killed poor workers in Shanghai, he began to speak at anti-imperialist demonstrations, bringing him into contact with future Communist leaders. While acting as chair of the Department of Literature at the University of Guangdong in Guangzhou, he first encountered Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. The latter arranged for Guo to become head of the National Revolutionary Army’s Department of Propaganda when the Northern Expedition started in June 1926. After the Shanghai Massacre of 1927, when Jiang Jieshi and the Guomindang turned against the Communists, the latter staged an uprising in Nanchang in 1927. When it was crushed, Guo fled to Japan, where he would stay there for the next 10 years, becoming the foremost expert in the categorization of the “oracle bones” (甲骨) of ancient China. In 1931, he completed the treatises "Research on Oracle Bone Inscriptions" (甲骨文字研究) and "Research on Yin and Zhou Bronze Inscriptions" (殷周青铜器铭文研究).

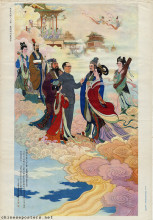

In 1937, when the Anti-Japanese War broke out, he returned to China to participate, breaking all ties with his Japanese family, even refusing to see his former wife after the war ended. In April 1938, he served as director of the Third Department of the Political Department of the Military Commission of the National Government, but stayed away from most of the fighting. There, he wrote a series of traditional operas that merged old and new, elite and popular art forms, making them relevant to the present. In the most famous, “Qu Yuan” (屈原, 1942), Guo portrayed the ancient poet as a man of the people, defending their rights and the nation’s honor in the face of foreign invasion and a tyrannical king reminiscent of Jiang Jieshi.

After Lu Xun’s death, Guo became the next intellectual to lead the Chinese arts and philosophy world. The prominent positions he was given after 1949 further enabled him to do so: Vice Premier of the State Council; Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress; Director of the State Culture and Education Commission; the first President of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, thus giving him control over the nation’s intellectual line.

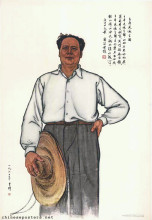

Laughing and talking makes people happy, and I am happy to hear that China is full of youth, 1979

With the start of the Cultural Revolution, the protection from Mao he had enjoyed ended and as a "cultural czar", he became one of the first to be attacked. His operas now were considered bourgeois. Guo denounced old friends and colleagues and hurriedly distanced himself from all his previous work, insisting it should be burned. Foreign commentators were amazed about the ease with which such a rebellious and fiery writer had turned, apparently uncoerced. Guo bent his assessments of classical poets to whatever Mao preferred, praised his calligraphy as the “pinnacle” of the genre, and wrote poems fervently praising Mao and his wife Jiang Qing. None of this saved his family, with two of his sons either committing suicide or being murdered, but it did help him to return to prominence; he was chosen by Mao as "the representative of the rightwing" in the 9th National Congress of the CCP in 1969 and his lavish lifestyle was restored. This included the house that now serves as his memorial museum, previously a residence of the Qing Dynasty official Heshen (18 Qianhai Xijie, Xicheng District, Beijing). Once the Gang of Four was overthrown in 1976, he labored on his deathbed to undo some of the damage of his sycophancy. Jiang Qing got special treatment as a “White-Boned Demon,” “swept away by the iron broom.”

Despite all this, Guo remains a revered intellectual and scholar.

Alex Colville, "Mao's 'shameless poet': Guo Moruo and his checkered legacy", The China Project, 21 September 2020

"Guo Moruo", New World Encyclopedia

![The Founding Ceremony of the Nation [PLA calendar 1985]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/e13-105_0.jpg?itok=WAZRw63q)