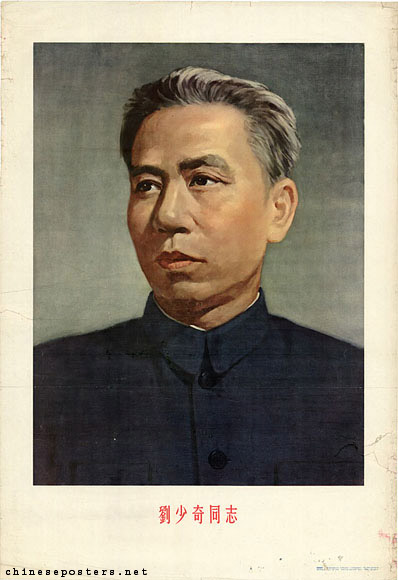

Until the Cultural Revolution, Liu Shaoqi (刘少奇, 1898-1969) was considered to be the successor to Mao Zedong. Born in 1898 into a rich peasant family in Hunan, he studied at the same school in Changsha where Mao had established the 'New People's Study Society'. In 1921, he joined the Communist Party; that same year, he went to Moscow where he studied at the University of the Toilers of the East. After his return to China in 1922, he became an active organizer in the labor movement, first openly, later underground. In 1925, he became the first chairman of the newly established All-China Federation of Labor. In 1927, he was elected to the Central Committee, where he would serve until 1968; in 1931, he was made a member of the Politburo.

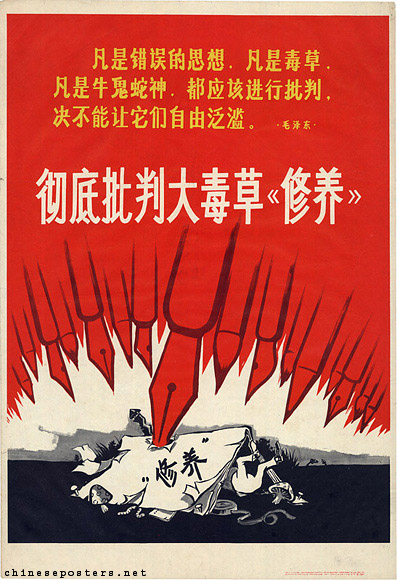

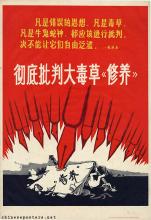

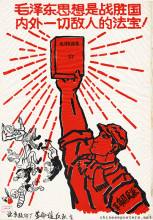

After completing the Long March (1934-1935), Liu was active both in Yan'an and in the so-called white areas (territory neither occupied by the Japanese, nor governed by the Guomindang or the CCP). While in Yan'an, he published his famous treatise How to be a good Communist (1939), which stressed the need to cultivate - almost in a Confucian manner - revolutionary behavior and thought.

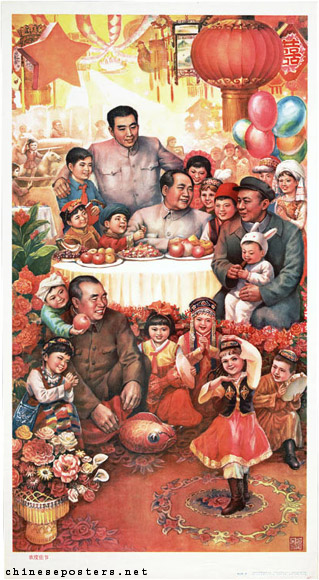

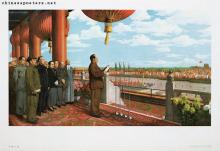

Comrades Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De, Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun together, 1982

After the founding of the People's Republic, Liu served in most of the governing bodies on the central level, including the CC Standing Committee, the Politburo, and the National People's Congress. In 1959, he replaced Mao as State President and visited many friendly foreign countries. His sixth wife, Wang Guangmei (王光美), usually accompanied him on these trips.

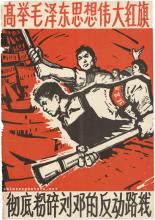

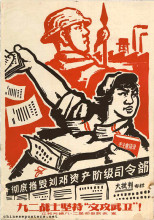

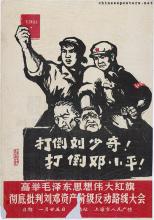

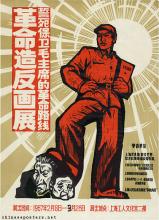

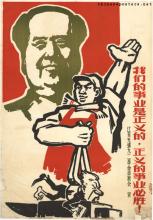

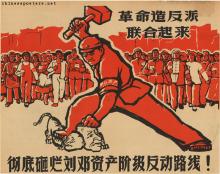

The renegade, traitor and scab Liu Shaoqi must forever be expelled from the Party!, 1968

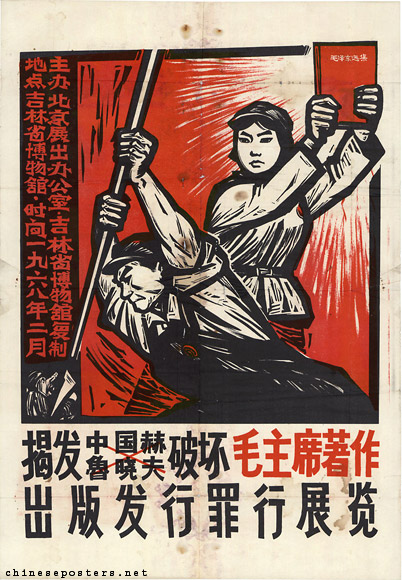

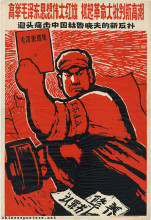

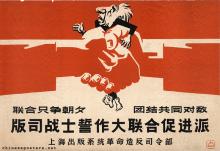

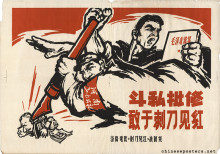

In 1966, Liu and Deng Xiaoping became the major targets of struggle during the Cultural Revolution. They and Mao basically disagreed on the course of development China ought to take. Mao, moreover, feared that Liu's and Deng's policies would tarnish his revolutionary status. Although Liu tried to follow Mao's policies as much as possible, the Chairman was convinced that Liu had to go. While Liu still attended Mao's eight receptions of Red Guards in Beijing in August-November 1966, he increasingly became the target of Red Guard (and Mao's) criticism.

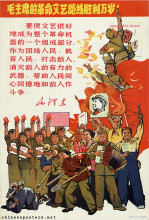

Thoroughly criticize the great poisonous weed of "How to be a good communist", 1967

In October 1966, Liu made his first 'self-criticism', but to no avail. By November, he was accused of being the "supreme leader of a black gang", and by January the following year branded as "China's Khrushchev" and "the No. 1 Party person in authority taking the capitalist road". Both Liu and Wang Guangmei were severely struggled against by Red Guards. In October 1968, Liu was officially denounced as "a renegade, traitor and scab hiding in the Party, a lackey of imperialism, modern revisionism and the Guomindang reactionaries", formally stripped all his positions and permanently expelled from the Party. He died in a Kaifeng prison, allegedly because he was refused medication for diabetes.

Celebrating a festival with jubilation, 1983

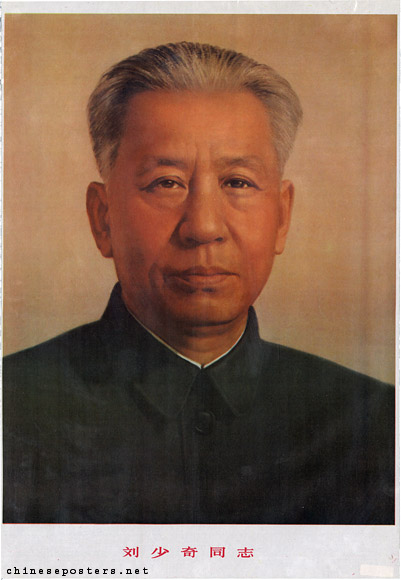

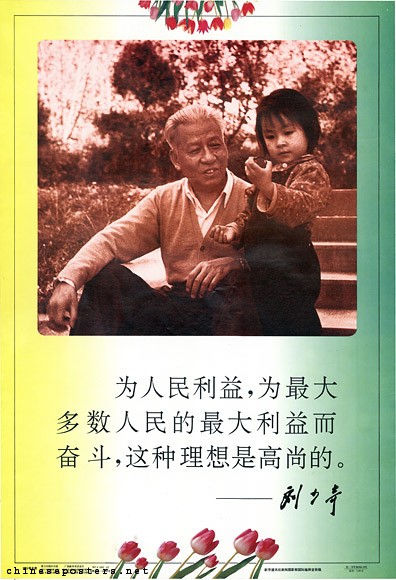

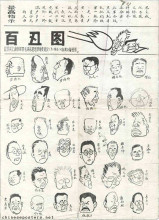

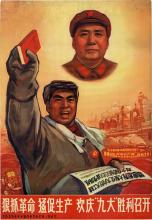

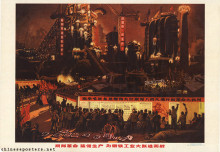

Only in 1980, Liu was formally rehabilitated, in conjunction with the reappraisal of the historical role of Mao Zedong. From that period on, he could be seen again, together with Mao, Zhou Enlai and Zhu De, on the numerous posters dedicated to the first generation of leaders. As proof of his regained stature, one of the four memorial rooms that were added in December 1983 to the Memorial Hall where Mao's remains were on display was dedicated to Liu. By the late 1990s, Liu's solo picture as well as his quotations reappeared on posters.

Dachang Cong, When Heroes Pass Away - The Invention of a Chinese Communist Pantheon (Lanham MD: University Press of America, 1997)

Lowell Dittmer, Liu Shao-ch’i and the Chinese Cultural Revolution - The Politics of Mass Criticism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974)

Huang Zheng, "The Beginning and End of the 'Liu Shaoqi Case Group'", Chinese Law & Government 29:3 (1996), 7-23

Guo Jian, Yongyi Song & Yuan Zhou, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006)

Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Volume III: The Coming of the Cataclysm (Columbia University Press, 1999)

Rudolf G. Wagner, "Reading the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Peking: The Tribulations of the Implied Pilgrim", Susan Naquin & Chün-fang Yü (ed), Pilgrims and Sacred Sites in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992)