Ever since Xi Jinping first used the phrase “Chinese Dream” in a public pronouncement, people inside and out of China have been struggling to come to terms with what this concept entails. Xi first spoke of the Chinese Dream after his election as General Secretary in 2012, during a speech he delivered after visiting the exhibition "The Road to Rejuvenation" at the National Museum of China in Beijing. The exhibition focuses roughly on the period of and experiences with Sino-foreign contacts since the mid-19th century, in short, with the "century of humiliation" in Chinese official discourse. Over time, it has become clear that the Chinese Dream consists of "realizing a prosperous and strong country, the rejuvenation of the nation and the well-being of the people". The Chinese Dream has been presented as a comprehensive concept that consists of four parts: a Strong China (economically, politically, diplomatically, scientifically, and militarily); a Civilized China (equity and fairness, rich culture, high morals); a Harmonious China (amity among social classes); and a Beautiful China (healthy environment, low pollution).

With one heart to build the Chinese Dream together, ca. 2013

Roots of the Chinese Dream

Although Xi’s adoption of the Chinese Dream was new, the concept already had been in vogue in the past. Some scholars trace its emergence to the period after the end of Empire in 1911; others insist that the Chinese Dream resulted from the long-lasting discourse of national rejuvenation, victim mentality and rising nationalism; yet others trace it to Mao Zedong’s 1956 speech "Strengthen Party Unity and Carry Forward Party Traditions", which presaged the Great Leap Forward Movement (1958-1960). As for the Chinese Dream’s focus on the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people, some see a direct link with the concept of the "invigoration of China" that Deng Xiaoping put forward in the 1980s. Jiang Zemin used the exact phrase in the 1990s; Hu Jintao expressed his support for it; and now Xi has made it into the cornerstone of his policy, a "mission statement" for the CCP.

These considerations, first, show that Xi’s political ideas are no heresy, but are firmly grounded in CCP tradition and ideological orthodoxy. Secondly, they indicate that while Xi is pursuing policies that were enunciated earlier, he is shifting course in a direction he finds necessary for the nation. And thirdly, by charting a new course, Xi signals his personal authority and asserts his power.

The Chinese Dream is the dream of a strong army, 2013

Definition of the Chinese Dream

It has been difficult to define what the Chinese Dream means exactly, or how it can be realized. Xi’s 2012 Chinese Dream speech was welcomed with great fanfare and led to a flurry of activity. The institutions and departments responsible for publicity and propaganda organized study meetings and seminars to produce articles, visual materials, television programs, public service adverts, popular songs, events and activities. Within a very short period of time, the Chinese Dream turned into a slogan in which all official activity was framed. At the same time, ordinary people, scholars, (party) officials, (public) intellectuals, and others remained puzzled about its meaning. The question of meaning is not irrelevant: ideological campaigns spell out China’s domestic ambitions and give an impression of its international intentions. The process of defining and realizing the Chinese Dream has been scrutinized mainly for its patriotic undertones, its International Relations’ implications and China’s position vis-à-vis the world in general. These aspects are important, interesting and very relevant, but the focus here is on how they are presented domestically and propagated among the people. As for China's international image, that is increasingly tied in with the policy of "One Belt One Road" (一带一路): the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Economic Maritime Silk Road. This Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is seen as a key instrument in achieving the Chinese Dream, aimed at legitimising China’s re-emergence as a world power after the century of humiliation it has suffered at the hands of Japanese and Western imperialism. Xi Jinping first referred to the BRI in October 2013.

The Chinese Dream: a prosperous and strong country ..., 2013

The easiest solution to the problem of defining the meaning of the Chinese Dream is to consider it simply as a tifa, a formulation, a concept, an empty but flexible container that can hold everything one likes at any given time. The tifa definition is a very attractive solution, putting the Chinese Dream on the same level as Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Up, Jiang Zemin’s Three Represents, and Hu Jintao’s Harmonious Society. In all these cases, every policy, every development, every action, every mode of thought could be subsumed under the name of the movement. On a more specific level, one can define the Chinese Dream as having three categories: the dream of the individual; the dream of the citizen; and the dream of the nation. As Ane Bislev elucidated in 2015, “[T]he elusiveness is to a large extent caused by the attempt to incorporate many different layers of society into the Dream. It is collective as well as private […] It is at once a dream of a strong and happy nation and a dream of achieving private happiness through the realization of personal goals.” While most people agreed with this in general terms, it proved impossible to pinpoint the relative order of these three categories in their opinion.

According to some, the personal dream should take precedence over the broader goals of nation and state. Others insisted that the personal, materialistic desires were all part of larger CCP-led efforts to establish a well-off society and could not be part of the Chinese Dream. They argued that by realizing the dreams of citizen and nation, personal dreams would be realized as a matter of course. Others again insisted that generational, occupational and wealth levels also should be taken into account. A newly graduated student’s dreams were not a migrant worker’s; and their dreams again might be opposed diametrically to those entertained by private entrepreneurs, members of the new middle class, pensioners or kindergarten students.

Visualizing the Chinese Dream

The imagery that has appeared on posters in support of the Chinese Dream after Xi’s speech can be divided roughly in two types: posters produced for official spaces and materials created for use in public. The first type of materials is designed for use in official venues, i.e., party-, government and army offices at all levels, (university, company and neighbourhood) meeting rooms, etc. The second type appears in display cases in the streets, on billboards, on rotating electronic or LED screens, on hoardings and scaffolding erected around construction sites, etc. The imagery and the messages of these two groups are significantly different. Formally, neither type of poster is on sale anywhere.

Together and with one heart build the Chinese Dream, 2010s

The materials used in official spaces amplify as well as echo the well-known themes of previous campaigns such as the one supporting the Harmonious Society. The posters tend to be large-sized and glossy and are (partially) devoted to showing China’s splendour and accomplishments: the Great Wall (symbolizing China); the Tian’anmen Gate Building (symbolizing the PRC); doves of peace; flower arrangements; modern cityscapes, etc. Xi himself features prominently on these posters, both in Western-style suit and Sun Yatsen jacket. On some posters, Xi is shown together with Prime Minister Li Keqiang, on others he is accompanied by the other members of the Politburo. These visual elements are generally accompanied by slogans closely associated with the Dream, such as "The Chinese Dream: A strong nation - A national revival - A prosperous population".

What, then, distinguishes the posters on the streets in major cities across China? After they where first presented in July 2013, they have become so omnipresent that one can argue that propaganda has returned with full force. The China Civilization Office under the CCP Central Propaganda Department (中共中央宣传部中央文明办主办) has made the Chinese Dream materials available online as high-resolution downloads. They range from posters to banners and desktop images for personal computers and smartphones, thus ensuring a unity of contents that no Chinese propaganda campaign has had before.

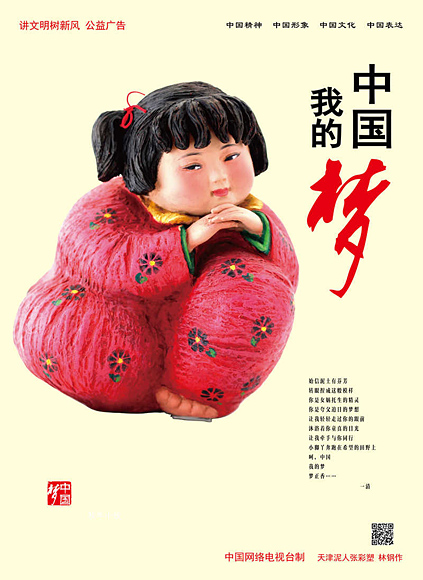

The Chinese Dream, my dream, 2013

According to Joyce Lee, writing in the Diplomat (2014), the posters focus on "[…] Confucian morality, traditional Chinese ideals, socio-economic adaptations, historical grievances, and everyday social activities. […] Epithets and images extoll Confucian values … ; other themes include thrift, economic prosperity, springtime renewal, and a Chinese way of life centered in honesty and sincerity.’ The posters make widespread use of ‘… traditional Chinese paper cuttings … Yangliuqing woodblock prints … Red-cheeked figures such as the one in the campaign’s primary image are made by the Nirenzhang clay sculpture workshop in Tianjin". In short, reassuring and comforting images drawing on traditional symbols crowd the urban gaze; none of them show Xi Jinping. The Nirenzhang clay figurine Meng wa, designed by Lin Gang, has become the ‘poster girl’ of the campaign. The poster showing her is seen most frequently, and she also features in many of the televised PSA in prime time.

Critical evaluations of these Chinese Dream materials are not easy to find, but some Chinese writers have tried to do so. Most critics see them as nothing but a vehicle to spread Xi Jinping’s words. They praise and extol Chinese civilization; spread the basic values of socialism; utter true words instead of empty phrases (this in itself is an aspect of Xi’s policies); and create a harmonious, beneficial social orientation. In other words, the posters do little to raise the people’s quality or awareness in a concrete sense. Moreover, even within the limited confines of the contents the critics identify, they see shortcomings, arguing that the materials are too much focused on the past and on tradition. A more fundamental problem is that although the majority of the materials can be seen in urban areas, they almost solely deal with an idealized, rural reality, and as such do not engage with what the intended audience is concerned about.

Heyday of the Chinese Dream, 2014

The "one-size-fits-all" approach of the Chinese Dream campaign means that it has to search for the lowest common denominator. However, this does not acknowledge the fact that modernized Chinese society has become better educated, more diverse and multi-faceted as well as media-literate. It raises questions about whether ideological themes still can be propagated in a traditional, centralized way, even when adopting modern techniques. It calls for a complete new way of thinking about communication strategies, the media that are used in the campaign, the contents that are addressed and the aesthetics that are employed.

The present Chinese Dream materials are focused (“too much”, some say) on the emerging urban middle class and its particular problems; they address issues that are only partially, or reluctantly underwritten by the audience; what that audience really cares about is left unsaid. One can argue that the more traditional sentiments expressed in the Chinese Dream campaign overlap with what has been identified at the CCP’s 18th Congress (2012) as the socialist core values. This indeed suggests that the campaign in the end may be less about national rejuvenation and more of an element used to bolster the legitimacy of the Party.

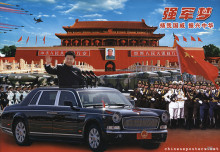

National soul Dream of a powerful nation, 2014

Glossies

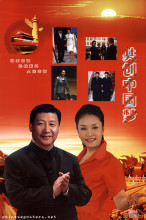

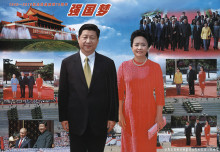

Apart from these official visual materials, the posters that have been put on the market for popular consumption can only be termed "glossies": colorful photo collages in high gloss, often featuring Xi Jinping and his wife, Peng Liyuan where the more official posters do not. These "glossies" do not focus on the China Dream themes. The Xi's are placed in front of significant and powerful symbolic images like the Tian'anmen Gate Building, the Great Wall, the Shanghai Pudong skyline, the CCTV Headquarters, the Chinese Space Station, high-speed trains, etc. A substantial number of these posters address the strength China will derive from attaining the Dream; phrases like "The Dream of a Strong Army -- the China Dream" and "The Dream of a Strong Nation" are rife. Xi is dressed either in Western suit or Sun Yatsen suit; Ms. Peng is dressed in signature Chinese design dresses, with matching accessories like handbags. These posters tend to end up on the walls of small shops.

Ane Bislev, "The Chinese Dream: Imagining China", Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences (2015) 8, 585-595

Cai Yiwen, "The New-Style Family Values Underpinning the ‘China Dream’", Sixth Tone, 19 July 2021

William A. Callahan, China Dreams -- 20 Visions of the Future (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013)

Benjamin Carlson, "The World According to Xi Jinping", The Atlantic, 21 September 2015

China Civilization Office, CCP Central Propaganda Department, Jiang wenming shu xinfeng gongyi guanggao (Practice culture, establish a new practice public service advertisements) (2013) (http://www.wenming.cn/jwmsxf_294/zggygg/)

James Farrer, "Multicultural Dreaming: Democracy and Multiculturalism in the 'Chinese Dream'", in Nam-Kook Kim (ed.), Multicultural Challenges and Sustainable Democracy in Europe and East Asia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 15-35

Michael X.Y. Feng, "The 'Chinese Dream' Deconstructed: Values and Institutions", Journal of Chinese Political Science (2015) 20, 163–183

Anne Henochowicz, "I Love the Chinese Dream; A Coffee, Please, and Cream", China Digital Times, 6 February 2015 (

Jennifer Hubbert, "Of Menace and Mimicry: The 2008 Beijing Olympics", Modern China 39:4 (2013), 408–437

Ian Johnson, "Old Dreams for a New China", The New York Review of Books Daily, 15 October 2013

Jyrki Kallio, "Dreaming of the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation", Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences (2015) 8, 521–532

Robert Lawrence Kuhn, "Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream", International Herald Tribune, 4 June 2013 (accessed 29 January 2014)

Stefan R. Landsberger, "China Dreaming. Representing the Perfect Present, Anticipating the Rosy Future", in: Valjakka, Minna & Wang, Meiqin (eds.), Visual Arts, Representations and Interventions in Contemporary China: Urbanized Interface (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018)

Stefan R. Landsberger, "Harmony, Olympic Manners and Morals - Chinese Television and the ‘New Propaganda’ of Public Service Advertising", European Jounal of East Asian Studies, 8: 2 (2009), 331-355

Joyce Lee, "Expressing the Chinese Dream", The Diplomat, 28 March 2014

Li Wei & Deng Jiaohua, "Dangdai gongyi guanggao chuangzuo zhong de chuangtong wenhua yuansu jueze yanjiu - dui Zhongguo meng gongyi guanggao chuangzuo de fansi" (Research on the selection of traditional cultural elements in creating present day public service advertising - Reviewing the creation of Chinese Dream public service advertising), Wenxue shenghuo - Yishu Zhongguo 968, 2014, 124-127

Chunlong Lu, "Urban Chinese Support for the Chinese Dream: Empirical Findings from Seventeen Cities", Journal of Chinese Political Science (2015) 20, 143–161

Yuxi Nie, Micro-Blogging and Media Policy in China -- Xinhua’s Strategic Communication on the Belt and Road Initiative, unpublished PhD Dissertation, Leiden Univerity 2019

Michael Schoenhals, Doing Things with Words in Chinese Politics -– Five Studies (Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, 1992)

Jon R. Taylor, "The China Dream is an Urban Dream: Assessing the CPC’s National New-Type Urbanization Plan", Journal of Chinese Political Science (2015) 20, 107–120

Zheng Wang, "The Chinese Dream: Concept and Context", Journal of Chinese Political Science (2013/4) 19, 1–13