Already in 1959, after the Lushan Plenum where Lin Biao replaced Peng Dehuai as Minister of Defense, the intense involvement of the PLA in internal political power struggles started. Lin’s standpoint, framed in the slogan of the "Four Firsts" (men over weapons; political over other work; ideological over routine work; ‘practical thought’ over book-learning), closely corresponded with Mao’s ideas of the direction China should take after the disasters of the Great Leap Forward. As a result, while political power ostensibly continued to grow from the barrel of the gun, as Mao insisted, the CCP decreasingly succeeded in controling that gun.

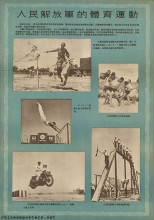

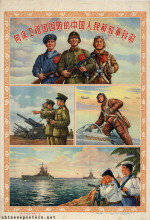

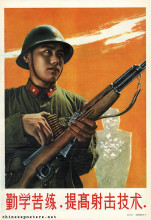

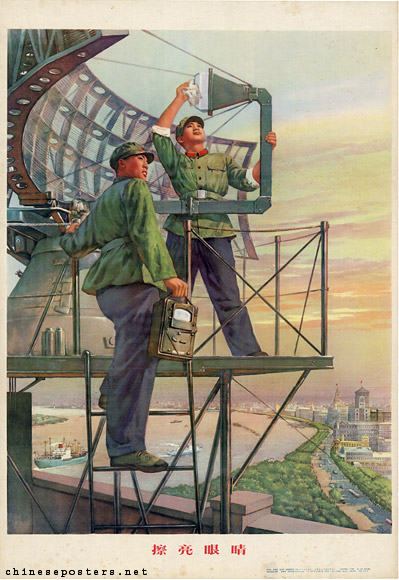

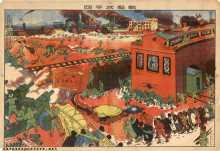

Study the People’s Liberation Army’s hard work and plain living, 1966

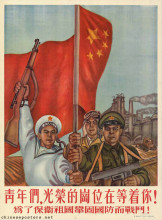

In the early 1960s, Lin put Mao’s ideas into action and reformed the Army: party membership was expanded; party branches at the lowest levels were reorganized and expanded; ideological training of officers was stressed and the class background of Army personnel was more closely scrutinized; ranks and the distinctions of ranks were abolished. Mao liked what he saw taking place in the PLA, and this bolstered the political profile of the Army and of Lin.

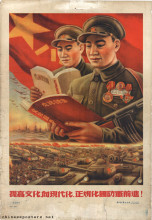

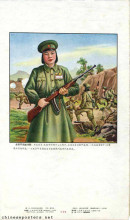

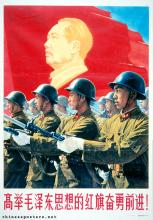

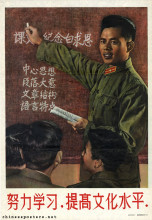

The publication of Mao’s quotations in the so-called "Little Red Book" in 1961, which started in the PLA, no doubt made Mao look even more favorably on Lin and his organization. Military martyrs (Lei Feng, Wang Jie, Dong Cunrui, Ouyang Hai and many others) became models for study by the population, and in 1964, the "great school" of the PLA itself was made the object of national study in the "Learn from the PLA"-campaign. One study theme was the famous Three-Eight Work Style, expressed in three phrases and eight characters. The phrases were: a firm and correct political orientation; an plain, hardworking style; and flexibility in strategy and tactics. The eight characters stood for unity, alertness, earnestness and liveliness.

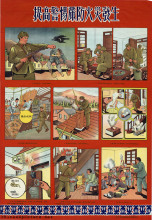

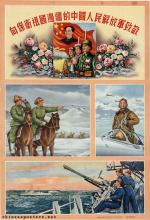

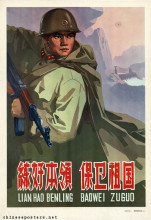

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army is the great school of Mao Zedong Thought, 1969

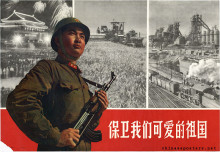

With the dispatch of military officers to take over government offices and state-owned enterprises, the PLA’s political control system was introduced in many civilian units, leading to a general militarization of the people. This trend was strengthened by the formation of the people’s militia, making everyone a soldier.

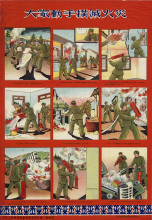

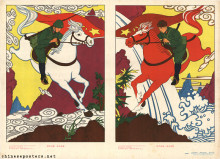

Study the fine workstyle of the PLA (1), 1964

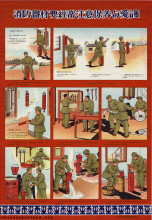

Study the fine workstyle of the PLA (2), 1964

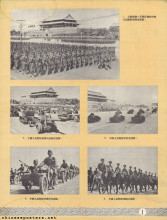

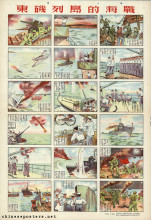

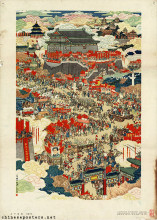

Once the Cultural Revolution started in earnest, the Army was not allowed to intervene in what emerged as a civil war between the various factions of Red Guards and Red Rebels. The PLA was ordered by Mao to "support the left" by standing aside, even when their arsenals were looted by the civilian combatants. When the chaos reached its climax, when the Party was in disarray and the economy had come to a virtual standstill, the Army appeared to be the only functioning organization left, and Mao turned to the PLA to restore order. As a result, the PLA emerged from the chaos with greatly increased position and power: senior Army men headed the newly-formed revolutionary committees responsible for local administration; almost half of the Central Committee members elected in 1969 were soldiers; and half of the State Council members in 1971 belonged to the PLA.

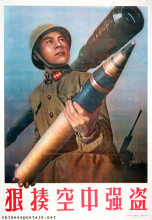

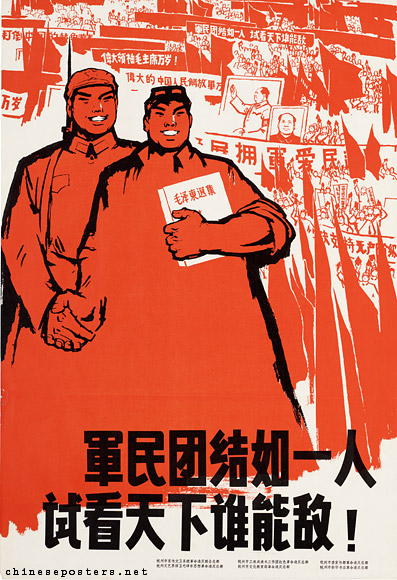

Army and people are united, who dares to oppose us? 1966-1967

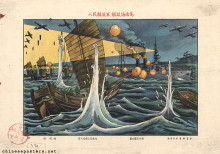

Once Lin Biao fell from grace in 1971 and his supporters were purged, the PLA’s model function as the "great school of Mao Thought" ceased to be stressed. Instead, the close relations between the Army and the people were propagated once more ("as close as fish and water"). With the percentage of military men in governing bodies declining steadily over the years, the importance of the military establishment seemed to lessen. This impression is belied, however, by the crucial role PLA-elders such as Ye Jianying played in Hua Guofeng’s rise to power, his arrest of the Gang of Four, and his subsequent replacement by Deng Xiaoping. It seems safe to say that the relationship between the military and the Party has changed: the Party no longer holds the gun, but the PLA needs the Party to survive.

With the red sun in our hearts, we trample the difficulties under our feet, 1971

Flemming Christiansen & Shirin Rai, Chinese Politics and Society - An Introduction (London: Prentice Hall, 1996)

K.H. Fan (ed.), The Chinese Cultural Revolution: Selected Documents (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1968)

Helmut Martin, Cult & Canon - The Origins and Development of State Maoism (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 1982)

Andrew J. Nathan & Robert S. Ross, The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress - China’s Search for Security (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997)

Michael Schoenhals (ed.), China’s Cultural Revolution, 1966-1969 - Not A Dinner Party (Armonk: M.E Sharpe, 1996)

Yang Kelin (ed.), Wenhua dageming bowuguan [Museum of the Cultural Revolution] (Hong Kong: Dongfang chubanshe youxian gongsi, Tiandi tushu youxian gongsi, 1995) [in Chinese]

![[Model soldiers]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/d91-102.jpg?itok=0UWMRPtU)